June 8, 2023

Screening: Tahani Rached’s FOUR WOMEN OF EGYPT and Heiny Srour’s THE SINGING SHEIKH

Anthology Film Archives

32 2nd Ave, New York

Thursday, June 15, 2023

7 pm

Join us for the first in an ongoing series of Bidoun-curated screenings at Anthology Film Archives that privilege rare and/or underappreciated films. For the inaugural installment, we’ll be presenting the cult favorite documentary Four Women of Egypt from Egyptian-Canadian director Tahani Rached. Her film will be preceded by The Singing Sheikh, a short by Lebanese director Heiny Srour on the iconic dissident Egyptian folk musician, Sheikh Imam.

The screening will include:

Tahani Rached

Four Women of Egypt

1997, 89 min, digital

In Arabic and French with English subtitles

A portrait of four friends in Cairo (Wedad Mitry, Safinaz Kazem, Shahenda Maklad, and Amina Rachid), all born under colonial occupation, and all former political prisoners under Sadat. Despite ideological differences, the women maintain their friendships – sustained by their humor, warmth, commitment to politics, and shared ideals of social justice. Four Women of Egypt is a testament to both friendships and politics that have endured the violence and disappointments of 20th-century Egypt.

preceded by:

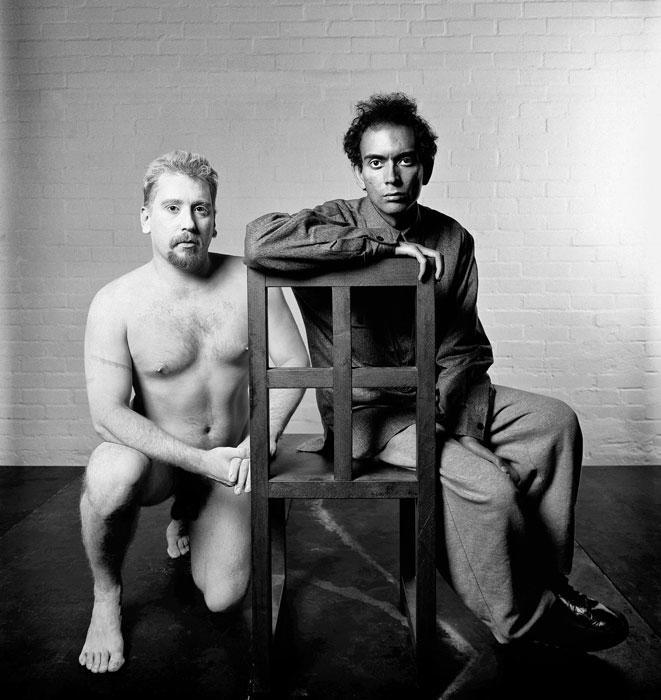

Heiny Srour

The Singing Sheikh

1991, 11 min, digital

In Arabic with English subtitles

A rarely-seen documentary on Sheikh Imam, the legendary and frequently imprisoned Egyptian folk musician whose political songs fearlessly indicted the ruling classes.

Total running time: ca. 105 min

$12 General Admission / $9 Seniors and Students

Tickets available at the box office or at the Anthology Film Archives website