In 1981, A Washington, DC, Punk band named Minor Threat released a song called “Straight Edge.” The lyrics, as barked by the lead singer, Ian Mackaye, delivered an unequivocal rebuke to punk-rock hedonism:

I’m a person, just like you

But I’ve got better things to do

Than sit around and fuck with my head

Hang out with the living dead

Snort white shit up my nose

Pass out at the shows

The song lasts all of forty-five seconds, barely enough time for two verses and a chorus that sounded like an unlikely rallying cry: “I’ve got the straight edge!” The name stuck, and in the next few years “straightedge” emerged as a kind of punk-rock temperance movement, a teenage rebellion against old-fashioned teenage rebellion. As MacKaye sang in a different song: “[I] don’t smoke / I don’t drink / I don’t fuck / At least I can fucking think.”

MacKaye always says he didn’t mean to start a movement. But for kids (as they were always called) all across the country, straightedge was a revelation, proof that punk could be (as the kids liked to say) “positive.” You might say that punk rock was moving beyond politics into ethics. Except that many of the straightedge bands that came up in the American 1980s weren’t particularly political. Uninterested in storming the barricades, let alone changing the world, straightedge kids created their own little worlds, which they called scenes. Many of them didn’t even identify as punk—they were hardcore, tough young kids who seemed a world away from the artsy ironists who popularized punk rock in the 1970s.

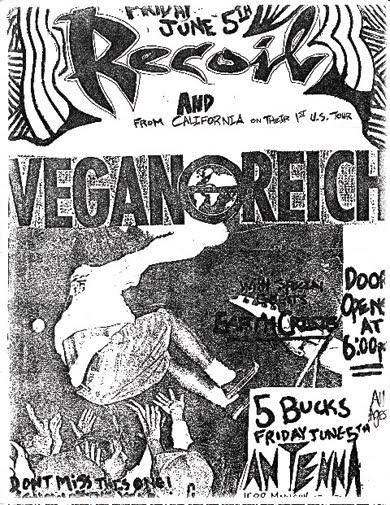

“Straightedge” didn’t necessarily mean “clean-cut”: there were hot-headed jocks, earnest activist types, and plenty of kids who were in it for the music, as well as the seductive air of (very) righteous indignation. It was, in a sense, a whole movement dedicated to extremism in defense of virtue… and yet one band of extremists found a way to make everyone else seem downright slack. They named themselves Vegan Reich. Their four-song debut included a foldout manifesto for a philosophy called hardline, which was not only straightedge and vegan but also anti-abortion and arguably anti-gay. “The time has come,” it began, “for an ideology and for a movement that is both physically and morally strong enough to do battle against the forces of evil that are destroying the earth (and all life upon it).” Vegan Reich’s sound was fast, bare-bones punk, with a hint of heavy metal, and it seemed to have been calibrated to incite maximum bedlam at concerts. The vocalist was a mixed-race shouter who delivered his rants with a little bit of melody and a whole lot of furious certainty. One song began, “Fuck you, shut your fucking mouth / We didn’t ask for your opinion” (although without the lyric sheet, it might have been hard to tell).

That shouter was Sean Muttaqi, a Southern California kid who took a circuitous route to straightedge; one of his biggest inspirations had been Rudimentary Peni, a caustic British anarcho-punk band. And with Vegan Reich, he helped make the world of straightedge a little bigger and a lot more complicated, delivering a confrontational message of abstention (from drugs, exploitation, and animal products) and all-around defiance. It wasn’t long before punks across the country were debating, mocking, or following Vegan Reich. There had always been conservative currents in straightedge, but some people who heard (or, more likely, heard about) Vegan Reich saw the band as evidence that the movement had gone beyond the pale.

Then, before they had a chance to release a full-length album, the members of Vegan Reich called it quits. Kind of. The same kids were soon playing a fusion of reggae and hardcore as Captive Nation Rising, which eventually morphed into a more traditional reggae band. For Muttaqi, it was just the beginning of an odyssey. He started a label, Uprising Records, which helped incubate the future pop stars in Fall Out Boy. He taught martial arts. And, after years of study, he became a Muslim.

Vegan Reich reunited and released a three-song CD, Jihad, in 1999. Another reunion is planned for this summer. But fans waiting for Muttaqi to launch an in-your-face Muslim hardcore movement will likely be disappointed. Instead of writing manifestos, he’s reading (and occasionally writing) scholarly articles, rethinking the history of animal sacrifice in Islam. He’s doing a lot of writing lately—he’s hard at work on a memoir about his “three decades of resistance.” And one night this past fall, with his wife and two daughters occasionally audible in the background, he agreed to talk about his long, non-linear journey from resistance to submission.

Bidoun: When did you first get into punk?

Sean Muttaqi: I think I first heard punk rock in 1979. We had just moved out of a pretty rough neighborhood, and I got exposed to skate culture and punk culture and got into punk-rock rebellion. If you look at the rebellious aspects of punk, it could go either way. Kids who had a rougher background, it kept them out of trouble. And kids who had a more middle-class, safe environment, it helped nudge them into trouble. I know guys from gang neighborhoods that left that lifestyle behind—they found punk and became peace-punks and vegetarians. Then you’d see them ten years later, doing the gang thing; the neighborhood took control again. And then, on the other end, I knew middle-class kids that became junkies because of punk rock.

Bidoun: What about you?

SM: Well, I came from a working-class neighborhood, but after we moved, I was surrounded by middle-class kids. It was probably a good move, looking back at it — my cousins are now in jail and stuff. [Laughs a little.] Coming into punk at that time and being in the skate realm, we were into Black Flag, Social Distortion, the Dead Kennedys. I was lucky to have grown up in Southern California in the heyday of that scene. I was barely going to high school. I officially dropped out when I was sixteen and got fully immersed into going to shows in LA.

We were very nihilistic, talking about destroying this and destroying that. The SoCal scene was violent. I don’t mean that in a negative way, it was just this energy you couldn’t contain. There was this chaotic perception among everybody. You’d have a group of friends, and one would have a Mohawk, and the other would have Dickies and flannel on, and you’d all be listening to Black Flag. Everyone was searching for these identities, but they didn’t see it as a separate thing.

But I was also hearing stuff from England — stuff like Discharge and the Exploited. It was a natural progression for me — coming from a working-class background and being surrounded by all these middle-class kids that I couldn’t relate to, and then suddenly getting access to all these British bands that were talking about class issues. For me, once I discovered class and leftist opinions and all that, I moved to the anarchist punk scene really fast. But then I would go to these anarchist gatherings, and I would see really bad personal behavior. I think that was the two worlds that collided with me, going, “Hey, we need to be more political — but politics isn’t worth treating each other like shit.” Even before I got into the anarchist punk thing, I’d gone vegetarian, although it took me a couple more years to find out about veganism.

Bidoun: When the members of Vegan Reich came together, did you set out specifically to be a vegan straightedge band? Or did that come later?

SM: No, it was a thought-out conception — I was looking for people to start a militant animal liberation band. This whole time I was interacting with a lot of different activist communities, and from out of that we formed a tight-knit community. We were causing a lot of controversy in the anarchist community, pointing out the contradiction of people demanding freedom for humans and oppressing animals at the same time.

People started jokingly referring to us as vegan fascists, so that’s where the name came from. The notion was, If you’re going to call us Vegan Fascists, we’re going to call ourselves Vegan Reich.

Bidoun: Your first record, Hardline, came with a manifesto that called for people to live in accordance with “the laws of nature,” and to eschew “deviant sexual acts and/or abortion.” That shocked — and pissed off — a lot of people.

SM: For us, as animal liberation activists, the abortion thing was about consistency. Our view wasn’t the same as the right-wing Christian view of abortion; officially, hardline wasn’t saying that if a women was raped, she couldn’t get an abortion. We were saying that you need to acknowledge that life is life. It was more toward the animal liberation group: If you say that a shrimp is a life, and you shouldn’t kill it unless you absolutely need to eat, at least view abortion the same way. It can’t be used as birth control — that was hardline’s stance.

The homosexuality issue — that was tied to different influences at the time. For one, having come out of this punk-rocker anarchist thing — a lot of times, homosexuality was a hedonistic thing for some people. In retrospect, those aspects were influenced by morals, not necessarily politics. There was a conservative moralism there, the notion that sex was for family.

Bidoun: Obviously the band used provocative images — like the famous logo with the two crossed machine guns — and stirred up a lot of controversy. What were the live shows like?

SM: Well, we had a lot of friends in our local scene, and it didn’t really matter what we were saying. But I think in different parts of the country you definitely had people shocked by us having this violent persona…. People from, let’s say, the Midwest, would be like, “These guys have guns!” But in California, we knew peace-punks who had AK-47s in their trunks. They were dealing with skinheads and all sorts of other things.

Bidoun: Did people come to your shows looking to fight?

SM: I think people were more intimidated by us. Sometimes we had shows cancelled because people would call the venue and say they were going to bomb it or burn it down if we played. There were situations where people were there with the intent of arguing, but it usually didn’t go much further than that, although we did have our fair share of fights.

Bidoun: Did you ever wish that you didn’t have all the extra responsibility that came with the name and the image?

SM: Ah, yes and no. There was never regret about having named the band that, or having done what we did. But clearly, by the end, it just became impossible for us to function. Clubs were refusing to book us. You couldn’t pick up an issue of [the punk-rock magazine] Maximum Rocknroll anytime during the nineties and not see some reference to Vegan Reich or hardline. We would book a tour, and we’d get halfway across the country, and it would be cancelled.

Separate from that, my involvement with hardline — I didn’t regret having started it or having done it, but I found myself not happy with where it was going. We started hearing reports of actual right-wing people in Europe who were interested in us. It had started out as a fairly diverse group of people, but it became more and more a very white, middle-class, right-leaning type of thing. The same thing had happened to straightedge.

Even once I left, I still kept in touch with people who were doing it. But I had started my own journey. To me, it just led to other things. I think that hardline in some ways was already highly influenced by my study of Islam and Eastern religions. What’s funny is that hardline itself helped me move on from there.

Bidoun: Were you guys making a living from music?

SM: Yes and no. We were living so cheap, I mean, the whole band was living together in this place that was, like, three hundred dollars a month. So we could go on the road when we wanted to, or stay home and write articles, do whatever. We were pretty much free, it was a great creative time. And I had always been into martial arts, so in the early days of Uprising Records, when it wasn’t a full-time company, I was also a martial arts teacher. I was always able to operate outside the normal sphere of the system.

Bidoun: In the late 1980s and early 1990s, some of the kids in the New York hardcore scene allied themselves with the Hare Krishna movement, which also promoted a straightedge vegetarian lifestyle. Were you ever intrigued by the so-called Krishnacore scene?

SM: That happened at about the same time as hardline. Well, we already had this radical animal liberation thing going on, which was in conflict with their reliance on dairy products. But I think it came down to their whole notion of reincarnation, and how that tied into social injustice and suffering. In my mind, that was what really created conflict between us and them. We don’t buy that. We don’t buy that people or animals are suffering because of something they did before. Most people thought it was a very positive thing, because they were vegetarian and did all these cool things. But it didn’t seem that positive to us.

Some close friends, some who were marginally associated with hardline, ended up getting into that, and they’ve sort of made that their lives — you know, going back to India every year, in the same way that being Muslim is a major part of my life, now. I have a better view of the Krishna thing than I did then. I still disagree with it, theologically, as a Muslim, but I have a positive understanding of it as a spiritual path.

Bidoun: Were you raised with any religious tradition?

SM: Not really. God was a sort of aloof concept.

Bidoun: So how did you first come to Islam?

SM: When I was younger, my dad would give me books, and he also exposed me to Malcolm X’s autobiography. In the same era that I was getting into punk rock, the Iranian revolution was going on, and it made a big impact. So I had an understanding that it was a religion of the oppressed. If someone were to ask, in 1983, “What are your views of Islam?” — my answer might not have been long, but it would have been, “Something against injustice.”

Really, my first journey through spirituality came through the martial arts. I became more exposed to Taoism and meditation. I was also exploring Rastafarianism, and through that I was exploring the Old Testament and studying Christianity. In some ways, Islam was a balance, for me, between those realms, between East and West. And I had known Five Percenters, the Nation of Islam, things like that. So I was marginally exposed to the imagery of Islam. But it took some years until I finally decided to delve in.

Bidoun: How did you make the decision to call yourself a Muslim?

SM: Part of the hardline movement was the syncretistic thing, finding truth where it exists. I still think that’s a good approach. But the danger is that if you just pick and choose from a bunch of different traditions, the end-all, be-all of your decision-making process is you. That wasn’t the mentality of hardline. We had certain standards that everybody had to abide by. But at the end of the day, the decision about what is or isn’t a moral decision — it’s yours. I really felt like I had to find something that had standards and rules, teachings that I could accept and follow. Because otherwise it’s too easy: You come up against something that you don’t want to do in a certain situation, and you can just change your mind about whether or not that’s okay.

That said, I also didn’t want to jump into someone else’s religion, a different culture, and not be able to do it all the way. Probably since 1990, I had been completely sold on Islam’s view of the nature of God. And by 1993, I was saying, I want to convert, but I don’t want to convert and bring in my own ideas that are in conflict with the broader Muslim community. I didn’t want to come in and start arguing with people. The vegetarian thing was the final sticking point. So I started a journey to see if I could find an actual organic Muslim community that had vegetarian views, that existed within Islam — not converts bringing vegetarianism to Islam. It took some time, but eventually I came across the Bawa Muhaiyaddeen community, which was founded by a Sufi sheikh from Sri Lanka who had come to Philadelphia. I found a community where I could still maintain my veganism. That was a more important issue then than it is now, all these years later. And I’m still vegan, personally, but I’m not out there trying to argue that the Muslim world should become vegetarian.

Bidoun: Were there other conflicts between your old hardline identity and your new Muslim identity?

SM: No. Everything else was pretty natural. I really felt at home in my own skin, in some ways more than ever before. In a lot of ways, having a really diverse background — we have a lot of mixture in my family, everything from Mexican, French, Arab, Irish, Sicilian, African, and Cherokee — it just all felt real natural. The cultural and ethnic aspects were put to rest when I embraced Islam.

Bidoun: How had you identified before?

SM: You know, by the time I was old enough to have that become an issue, the punk rock thing had taken over. But when we moved to a new neighborhood, I was always the brown kid. On the other end, I can pretty much travel wherever and blend in, because I have this look that’s in between. If I’m in Jamaica, Jamaicans think I’m Jamaican; if I’m in an Arab country, the Arabs think I’m Arab; if I’m in Mexico, they think I’m Mexican. But for me, especially when punk and hardcore started losing the sense of community and ideology, Islam gave me a place to feel comfortable.

That said, it’s not as if we’ve adopted Arab culture, either. At home we tend to eat Mexican food; for Eid we make tamales…

Bidoun: Are the Muslims you meet surprised or shocked by your punk-rock past?

SM: It depends. There are a lot of Muslims in America who were born here — they’re Muslim and very American. And if it’s an African-American Muslim community, there’s a similarity there, because I spent a lot of time in hip-hop. But if it’s a more immigrant community, people might be more shocked by my background. I’ve had conversations with people who had no idea — trying to explain what punk rock was. Or, even if they did know about it, they’re like, “How do you come to Islam through that?” But for me, it wasn’t so much of an issue, anyway, because I don’t really stand out: I don’t have tattoos, and I look like pretty much everyone else there. I knew some other people who converted to Islam out of hardcore, that are just covered — you know, neck tattoos and everything. Clearly in their situation, it’s something that comes up more, because people are asking about it. But for me, in general, they wouldn’t realize I was a convert.

Bidoun: Is there ever a thought in the back of your mind that you’re not the same as someone who’s been Muslim his whole life, and for generations back?

SM: I feel the same as any Muslim, born Muslim or not. But I think that within the community, it’s important to defer to scholars. Sometimes people that came out of hardline or hardcore and became Muslim come to me to ask about this or that. I’m not a scholar, but I might guide them to a scholar that would know. If you’re talking about politics, then, yeah, as a lay Muslim, I feel fine giving my opinion. And as to the issue of vegetarianism in Islam, I feel fine speaking about it, because I’ve studied and I have an opinion and I’ll express it. But even there, when there were younger Muslims interested in vegetarianism, we went to the scholars and got rulings from them saying that it was permissible. At the end, it’s important for people to have these people — experts — they can go to. But that doesn’t mean that everybody is going to listen to everything they say.

Bidoun: Did you spend time trying to figure out how to reconcile your love of music with your Muslim faith?

SM: There was a certain period where I was like, “I’m just going to back out of the music thing, period.” But after studying, and reading hadith, and consulting different scholars, I came to terms with music’s place within Islam as a halal activity. That doesn’t mean it’s necessarily acceptable in every circumstance. And there were definitely moments when I felt conflicted about it. But everybody has contradictions. Sometimes I think that maybe we’ll move the record label into doing Muslim stuff. But then, if I’m doing this the Muslim way, we’re marginalized. And doing the label as we do it has enabled me to put out Amir Sulaiman’s record — he’s a Muslim poet. Personally, it’s a compromise I’m willing to make, at least at this point. Now, I may reach a point in my being or my faith, where I say to myself that I can’t do this, I can’t compromise anymore.

Bidoun: When you talk about your life, it seems as if there is a lifelong fascination with the idea of orthodoxy.

SM: Well, I would add to that — I would say that I have had a fascination with both orthodoxy and heterodoxy at the same time. I’m always interested in studying stuff that’s on the fringes of different religious currents. I love the Boxer Rebellion and all these Kung Fu mystical cults that existed, that were not mainstream Buddhism or mainstream Taoism. But whenever I study heterodox movements, I find that there are certain weird ideas that are there because of a leader, usually some charismatic person, who wanted to make allowances for himself. So at the end of the day, I always find myself drawn back to orthodoxy.