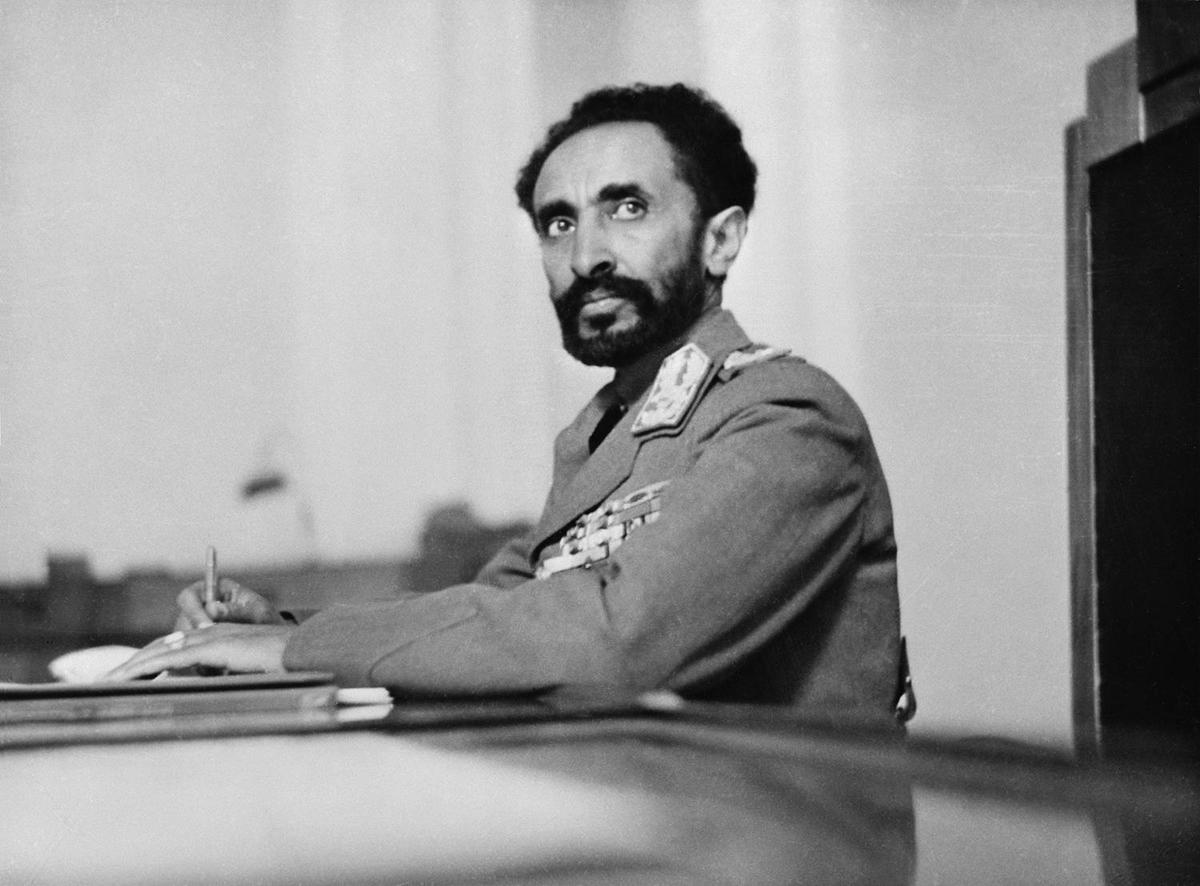

As the motorcade crept up Broadway, the shower of tickertape and confetti was so thick that one might have failed to notice Emperor Haile Selassie I, serene as a saint, buried in the pomp and protocol of his own welcoming. In 1954, the small yet dignified despot arrived in New York to partake in a liturgy of champagne toasts. Accompanied by the exotic Princess Semble and the thunder of a twenty-one-gun salute, the Ethiopian monarch impressed himself upon the Eisenhower White House, the deans of Harvard, the Boy Scouts of America, and the Redwoods of California. On this, his first state visit to America, Haile Selassie swapped Coptic crosses for autographed baseball bats, elephant tusks for honorary degrees, and confessed a taste for milkshakes. Wearing his field marshal uniform, as always, crested with ten rows of medallions, the Emperor flew to Hollywood, where he met Marlon Brando on set as Napoleon. Somewhat perplexingly, Brando exclaimed, “You’ve won more battles than I have.” (By most lights, Selassie’s signal military distinction was surrendering his country to Mussolini in 1936.)

At Stillwater Regional Airport in Oklahoma, the Emperor was met on the tarmac by a Native American in full Pawnee regalia, who gave the Conquering Lion of Judah a war bonnet and renamed him “Great Buffalo High Chief.” Governor Johnston E. Murray was more tongue-tied. “Welcome to Oklamopia,” he said. Before him stood that most inapproachable figure, the self-styled King of Kings who traced his lineage back to the Biblical Solomon and came laden with enough treasure for all three Magis combined — as a State Department memorandum would later put it, “Ethiopian court etiquette makes the Hapsburgs look breezy.” In the airport, Oklahoma had clumsily hung Ethiopia’s flag upside down, but what was up and what was down, anymore? Suddenly, as Lion became Buffalo, everything was sliding toward Oneness.

In 1927, the Jamaican-born Black Nationalist Marcus Garvey had prophesied, “Look to Africa, for there a black king shall be crowned.” Three years later, on November 2nd, 1930, Ras Tafari Makonnen took on the title Haile Selassie, “Implement of the Trinity,” in a lavish coronation ceremony designed to convince the world of Ethiopia’s civility, high style, and large portions. As the New York Times headline ran, “5,000 Cattle Slaughtered for Feast of 25,000 on Raw Meat and Wine — Americans at Ceremony.” Not just Americans — the BBC, National Geographic, and radio and film crews from across the globe had converged on Addis Ababa. During the gilded pageant, Tafari Makonnen became not only His Imperial Majesty but also Elect of God and head of the Ethiopian Orthodox Church, an unspoken declaration of his inviolability, the divine right of kings.

A few years later, Haile Selassie had been recognized as “the Messiah returned to earth” by Leonard Percival Howell and other apostles who founded a religion in Jamaica literally in his name. Garvey was declared His John the Baptist. In 1966, when Haile Selassie made his first state visit to the island, an estimated 100,000 Rastafarians awaited him at Palisadoes Airport in a cloud of sanctified smoke. His landing would ever after be known as Grounation Day, the second holiest day after the Coronation.

For his part, Haile Selassie rejected his deification. He claimed to be greatly distressed at being worshipped as Jah, and sent a missionary to Kingston in 1970 to establish the Ethiopian Church in Jamaica, confiding to him, “My heart is broken because of the situation of these people. Help them find the True God. Teach them.” And yet one might argue that Haile Selassie’s involuntary deification represents a perfectly appropriate response to the spectacles that he himself created. All the state banquets, motorcades, and photo ops — the pageantry of power celebrating itself — aims to instill reverence for authority and submission among its subjects. As the 3rd century theologian Origen wrote, in his commentary on the Song of Songs, “It should be known that it is impossible for human nature not always to love something.” It should also be known that it is impossible for human nature not to love too much.

On the tarmac, that temple of the accidental deity, America itself has been apotheosized. The first record of the worship of “John From America,” or John Frum, dates back to 1940, when reports from British colonial administrators on the island of Tanna in New Hebrides, today’s Vanuatu, warned that the natives had all stopped going to church and spoke of an American who existed in two places at once — beneath the seething red lava of the Mount Yasur volcano and in the United States, from whence he would arrive one day in an airplane, bringing with him great wealth. The prophecies came true two years later, when the US Army descended in a flurry of strange gear, military drills, and marching bands. The Americans occupied Tanna until 1945, only to vanish as suddenly as they had come, leaving behind lonely offshore islands of discarded supplies. Frumists dreaming of John’s return began to build airstrips and control towers, constructed an iconography of red wooden crosses and model aircraft, and enshrined as holy relics old Army jackets with sergeant’s stripes. (Later, photos of US astronauts on the moon.) In rituals that are still performed to this day, the faithful worship GI God in faded blue jeans, their bare chests painted with the letters U-S-A and wooden rifles slung over their shoulders. As one of John’s priests has put it, “The Promised Land is still coming, America will bring it,” along with “freedom and all things.” Like Haile Selassie, America itself has found this interpretation of the American Dream uncomfortable. US officials have variously blamed its deification on Japanese spies, “Axis influence,” the mental turmoil of wartime, “fifth column activities,” communist plots, misguided missionary policy, and even the work of Satan himself, with one Presbyterian minister, Charles McLeod, calling John Frum “the embodiment of evil” — a deeply peculiar form of self-loathing. And yet the deification of an all-American John as the God of Freedom is merely an especially literal reading of the message American soft power sends. For their part, the Frumists are quick to remind foreign journalists that to wait sixty years for a John is no more strange than to wait two thousand for a Jesus.

Perhaps islands are the perfect place to watch soft power pitches go awry, peripheral isolates where auratic hierarchies ramify out of control. At the other end of Tanna, members of the Yaohnanen community have come to worship an even unlikelier deity: Prince Philip, consort to Queen Elizabeth and brother of John Frum. According to Philipian apologetics, a villager gardening on the crater’s edge was impregnated by the volcano and gave birth to a son, who traveled overseas to marry a Queen and would in due time return to his home. The Philip cult was bolstered in 1974 when Queen Elizabeth’s notoriously boorish husband sailed into Tanna on the Royal Yacht Britannia. As Chief Jack Naiva, one of the paddlers in the war canoe that greeted the royals, remembered, “I saw him standing on the deck in his white uniform and I knew then that he was the true Messiah.” Prince Philip came and went, but his worshippers still hope the Duke of Edinburgh will return to Tanna to spend the last years of his life there. As Chief Naiva put it, “He won’t have to hunt for pigs or anything. He can just sit in the sun and have a nice time.”

Marx, writing of the distended cult of personality and near-divine self-regard of Napoleon III, famously observed, “Hegel remarks somewhere that all facts and personages of great importance in world history occur, as it were, twice. He forgot to add: the first time as a tragedy, the second time as farce.” When he heard about the cult a few years after his visit, Prince Philip established a long-distance relationship with his estimated four hundred worshippers, routinely exchanging portraits and trinkets. Islanders sent him a pig-killing stick — Philip sent back a photograph of himself, wielding it on the lawn of Buckingham Palace. (In fact, no pigs would die.)

On nearby New Hanover, a rival congregation that favored the American president Lyndon B. Johnson devised a kind of homeopathic ritual to bring their chosen one to his people. In the territory’s first democratic elections in 1964, islanders voted for LBJ and offered him $1,000 to come to New Hanover to rule over them. As thousands awaited his arrival at an election-night vigil on a mountaintop, LBJ was in the State Dining Room of the White House, towering over none other than Haile Selassie, in Washington on yet another state trip. As LBJ said in his toast to the Emperor: “With God’s help, we have always stood proud and free upon our native mountains.”

Another John-from-elsewhere, Brigadier-General John Nicholson, ascended to godhead in India in 1849. A hero from the First Anglo-Sikh War, the fierce and charismatic, “strong yet upright, even-handed” English sahib was appointed as district commissioner in the Northern Punjab, where he had once “striven manfully” against Sikh rebellion. According to an 1897 biography, “The name of this particular sahib was in every mouth.” A certain swami had declared Nicholson to be an incarnation of Brahma and began to preach at Hasan Abdal the worship of his new god, Nikalsain. Five or six others embraced the new creed, and a sect was born, gathering at daybreak to chant hymns to their adopted deity. And yet Nikalsain was a jealous god — as history has recorded, “Nicholson treated his apotheosis with unexpected vigour of speech and arm.” He beat his followers with a riding-whip, occasionally releasing them on the condition that they transfer their adoration to a fellow commander by the name of John Becher. As the biography records, “In one respect at least the Nikalsainis differed from the votaries of any other creed: their only persecutor was the divinity whom they adored.” Their god was admonished to control his temper by his superiors in the East India Company; when that failed, he was transferred to a different district.

Nikalsain exemplifies the greatest pitfall of godhood: it can go to your head. Though the Brigadier-General exemplifies gods behaving badly, even the most placid deity’s powers can be abused. In February of 1921, on an early speaking tour of what was then United Province (now Uttar Pradesh), Mahatma Gandhi, a self-styled ascetic, became a god unto the peasants of the villages of Gorakhpur. At a rally attended by over 200,000 people, the secularist leader of the Indian National Congress was seen as an avatar of Vishnu and greeted with shouts of “Gandhi-ki-jai” and floods of offerings. People told stories of the Mahatmaji’s miracles — smoke rising from wells with the fragrance of perfume, a stark raving Brahmin soothed by the invocation of the divine name, a girl who took a kernel of corn in her hands and blew on it, saying his name, and one kernel became four.

Yet the miracles attributed to Mahatma often fixated on lost wealth — stolen wallets returned, missing cows restored to their herd. Or he was seen as a wrathful god, punishing those who violated the Cow Courts or the Gandhian creed. The man himself was treated like a temple statue, moved from place to place to see and be seen. As the nationalist magazine Swadesh reported, “Outside the Gorakhpur station the Mahatma was stood on a high carriage and people had a good darshan of him for a couple of minutes.”

The state of Swaraj, or self-governance, that Gandhi preached, began to take on the trappings of moksha, salvation. One night an entire village stayed awake, banging on kettledrums and cymbals and shouting that it was the drum of Swaraj. They proclaimed that Gandhi had bet the English that he could walk through fire without being burned, with Indian self-rule in the balance; the Mahatma had taken hold of a calf’s tail and emerged unhurt. The story, which peasants were compelled to pass along (on pain of incurring the sin of killing five cows), underwent further elaborations involving a cow, an Englishman, and a Brahmin, plus the news that everyone’s rent would be reduced. This last detail excited still greater crowds to loot fairs and bazaars across the region, in one incident overturning stalls of sweetmeat and halwa. The editor of Swadesh, who had encouraged the devotional tendency in the district, promptly denounced the story. The real Gandhi, in turn, responded with printed statements that he was neither avatar nor god.

But his disciples did not believe him. When local activism entered a more militant phase in late 1921, the coming of a utopian Swaraj was interpreted as the direct supplanting of the authority of the police. In February 1922, an angry mob of Gandhians set the Chaura police station on fire, killing twenty-three policemen. “Maharaj Swaraj has come,” they chanted amid the flames. The veneration of the god of nonviolence had led to violence.

One may deify in order to defy. In 1921, the same year Gandhi went to Gorakhpur, General Jules Brevie described France’s civilizing mission: “However pressing may be the need for economic change and development of natural resources, our mission in Africa is to bring about a cultural renaissance, a piece of creative work in human material.” The following year, with the pacification of the desert Tuareg tribes, Niger finally became a French colony, administered, along with the other French West African territories, by the Governor-General in Dakar.

In 1925, at a social dance in a Songay village, the first gods of colonialism began to possess their human mediums. It was said they came on the wings of the Harmattan, the wind that blows south from the Sahara, in response to the new sense of powerlessness the French regime had wrought on the cosmos. The first Hauka spirit took the body of a woman and announced himself as Zeneral Gomno Malia, the Governor of the Red Sea. Then other gods began to appear: Istanbula, from Istanbul; King Zuzi, the colonial chief justice; Sekter, the secretary; and Kapral Gardi, the corporal of the guard. Soon, there was a whole pantheon of sergeants, foot soldiers, and petty bureaucrats. Every youth in the village had been possessed. Appalled at this bizarre turn of events, the district commander sent word to Niamey, the capital, where the commanding officer, one Major Croccichia, ordered the spirit mediums, sixty in all, to be arrested and imprisoned. Upon release, and having been expelled from their villages, the sixty-odd gods of the Hauka traveled from place to place and established new congregations. The movement spread rapidly. For his brutal suppressive tactics, Croccichia himself was soon deified as Krosisya or, Korsasi.

“Hauk’ize,” Istambula shouts, “Present yourselves for our Roundtable.” In order to oppose the state power, Hauka rituals partook in its officialdom. As infamously captured in Jean Rouch’s 1955 documentary Les maitres fous, possessed mediums would draw upon all the trappings of military regalia and protocol — in khaki and pith helmets, the deities goose-step and stamp across the sand, performing right-handed salutes and pouring out gin libations under a Union Jack. At the same time, foaming at the mouth and eyes blazing, the gods would do backflips and vomit black ink, burn themselves with torches, and plunge their hands into boiling cauldrons. In sacrifice, dogs were killed and eaten raw. When Les maitres fous was released, it was banned in the French and British colonies and received among some European audiences with disgust and horror, as they confronted a gruesome mimesis of themselves, a copy conjured up in a language that even subtitles could not translate. (The film has been received by African audiences in much the same way, but for different reasons.)

Some say the human body consists of flesh, the life force, and the double or bia, the self one catches sight of in shadows in the sand. To enter the medium’s body, it is said, the colonial spirit, invisible to all save the medium, places the bloody skin of a freshly slaughtered animal over the recipient’s head, capturing the double and securing it under the skin. When the spirit has firmly entrenched itself, the medium’s body has become the god. In this way, in occupied Niger, military deities occupied Songhay bodies and their worshippers in turn occupied the French colonial administration. (Occupy Colonialism!) By 1927, the Hauka cult had emerged as a political force. The religion founded villages in uninhabited areas of the countryside and set up its own, anti-French, society. Yet it continued to expand its pantheon and practices, as the colonial administration became more complex. Hauka began to possess government officials and army officers, eventually making their way into the Presidential Palace. In the 1970s, it was even said that the military dictator of Niger himself, General Seyni Kountche, was possessed by these same gods.

Under the animal skin sack, where the double lurks, is the inner space of influence, where ideas move over the waters like smoke. What the colonial gods and the gods of diplomacy and wartime occupation can teach us, in the accidents of their theogonies, is that if one truly wishes to coerce without violence — the manifest destiny of soft power — one must act in the dreamworld of the popular. And yet to achieve its ends, soft power so often overshoots the mark, producing uncanny doubles, parodies of power — not all of them laughable. Years after his ascension in the Punjab, Nicholson/Nikalsain led the British siege of Delhi and died the next day. Hearing the news of his god’s death, the last of the Nikalsaini swamis dug his own grave and slit his throat.

It is time for a new accidental god — a happy accident — who could cut across regimes and diplomacies and transcend contexts. In the 1920s, Deguchi Onisaburo, the charismatic, fez-wearing prophet of the Oomoto religion in Japan, had a bold notion — to worship L. L. Zamenhof, the creator of Esperanto, as a truly supreme being. Though Zamenhof was a Russian Jew who died too soon to witness his own apotheosis, he might have been amused by his 170,000 worshippers today, and by the quixotic Nativist movement — one that embraces humanity’s Oneness while upholding Japan’s essential superiority within it — for whom he is God.

And why not? It is impossible for human nature not always to love something, and impossible for human nature not to love too much. Zamenhof created his universal language, “Hopeful,” not just as a means of communication, but as a way to promote the peaceful coexistence of nations and enact his philosophy of Homaranismo, the universal love for humanity. A world in which Zamenhof is God is a soft world with hard consonants, which doesn’t sound so bad at all.