In late December of last year, Egyptian security forces wielding automatic weapons raided the offices of ten NGOs, among them American pro-democracy groups like the National Democratic Institute, International Republican Institute, and Freedom House, along with a number of Egyptian human-rights groups. Among the effects they plundered were computers, paper files, and, in at least one case, an office coffeemaker. The raid set off a frenzy of stories in the state-run press about the foreign provocateurs who had illegally received millions of dollars in order to sow unrest in the country. One Arabic language TV program, called al-Haqiqah, or “The Truth,” featured the confession of a former Egyptian employee, who claimed the organization was full of intelligence agents seeking to provoke sectarian strife… and who drank alcohol on the weekends. By the time formal charges were filed against forty-three defendants — including some nineteen Americans, sixteen Egyptians, three Serbs, two each Lebanese and Germans, a Palestinian, a Jordanian, and a Norwegian — a prosecutor revealed that the groups had been working “in cooperation with the CIA” and “serving US and Israeli interests.” At least one of the raids had yielded a Wikipedia map of Egypt divided into four parts. The foreigners wanted to carve up Egypt!

In February, a coalition of twenty-nine leading Egyptian NGOs issued a press release declaring their opposition to the crackdown and called for the immediate reform of a restrictive Mubarak-era NGO law that required organizations to register with the Ministry of Social Solidarity. The press release went on to decry the “slandering and intimidation” of civil society groups. Back in the US, the charges inspired growls in the Congress and talk of cutting the US’s annual $1.3 billion outlay to the Egyptian military. Presidential hopeful Newt Gingrich went so far as to liken the crackdown to the Iranian hostage crisis (seven of the charged Americans sought shelter at the US Embassy after being denied the right to leave the country).

Of course, denouncing foreign conspiracies is a time-honored tradition in Egypt; the House of Mubarak routinely discredited its adversaries as Israeli, American, or Iranian spies. And during the eighteen days of protest that led to the downfall of President-for-Life Hosni Mubarak, foreigners were routinely accused of sowing the unrest that had gripped Tahrir Square and the country at large.

Several theories have circulated as to what had inspired the crackdown. Some offered that the ruling Supreme Council of the Armed Forces had hoped to distract the country from a recent spate of violence. Others said it was born of a high-level feud between the Egyptian government and its American patrons. Yet others, seeing the hallmarks of Interior Ministry campaigns of past years, intimated that remnants of the former regime were trying to stir up trouble. Every single theory lingered on a woman named Fayza Abou El Naga, a steely-eyed but petite force of nature who, as Minister of Planning and International Cooperation, was a rare Mubarak-era holdover who had survived the revolution and was widely seen as the architect of the current crackdown. Abou El Naga, who is sixty-one years old, is frequently described as the most powerful woman in the Egyptian government.

Bidoun spoke to a number of individuals who have stakes in the ongoing drama — people who run human-rights organizations or art spaces, funders, activists, and one official from the Muslim Brotherhood. Fresh from parliamentary victories that have left it dominating the country’s first post-revolution legislature, the Brotherhood will surely play the most significant role in defining Egypt’s future. What follows is only the beginning of a conversation that is likely to be vast and vexed. This is not the first time we have looked into the contentious question of foreign funding in the Middle East, nor is it likely to be the last.

Issandr El Amrani is a freelance journalist and commentator. He blogs at Arabist.net.

Moukhtar Kocache is a former program officer for arts and culture at the Ford Foundation.

William Wells is director of the Townhouse Gallery.

Alaa Abd El Fattah is a blogger, software developer, and political activist.

Khaled El Qazzaz is a spokesperson for the Muslim Brotherhood’s Freedom and Justice Party.

Basma El Husseiny is director of Mawred, a cultural resource center. She is a former program officer for arts and culture at the Ford Foundation.

Oussama Rifahi is director of the Arab Fund for Arts and Culture.

Amr Gharbeia works at the Egyptian Initiative for Personal Rights.

Sarah Rifky is a writer and curator. She is the founding director of CIRCA (Cairo International Resource Center for Art).

Hossam El Hamalawy is a journalist, blogger, photographer, and socialist activist. He blogs at Arabawy.org.

Angela Harutyunyan teaches art history at the American University of Beirut.

Marwa Sharafeldin is a women’s rights activist. She is cofounder of the Network of Women’s Rights Organizations in Egypt, and NGOs including Fat’het Kheir and Nahdet el Mahrousa.

Participants were interviewed independently, and the text below reflects a quilt of their responses. With the exception of Oussama Rifahi and Angela Harutyunyan, who are based in Beirut, all interviewees live in Cairo.

What do you make of the current campaign against foreign funding and NGOs at large?

Amr Gharbeia: It feels more and more like the beginning of a campaign to target local NGOs, period. As much as I may not like NDI or Freedom House, I do worry that this is just the entry point to a crackdown on the NGOs we like. A lot might change, including the marginal freedom we’ve enjoyed these recent years.

William Wells: There’s no question this is the beginning of something. There’s been nonstop discussion about the whole business of Egypt’s reliance on America’s $1.3 billion in aid each year. We were in the coffee shop last week and there were some guys asking me about the Chinese — you know a few weeks back twenty-three Chinese workers had been abducted in the Sinai at a cement factory — and these guys at the coffee shop were like, “You really think there were twenty-three Chinese?” They thought it sounded fishy. But then a couple of security guys sitting nearby turned and said, “Yes, Chinese! You know, the Egyptians are buying weapons from them, too.” It sounds like the military has reached a point where they’re saying, frankly, we don’t need this money and we don’t want the restrictions that go with it. This is why they can snub the Americans, as if to say take your weapons and take your democracy money — they’re getting their weapons from elsewhere now. But you know, I have no idea. That’s just coffee shop talk.

Is there a sense that this is part of a pattern in Egypt, occasional scaremongering about foreign conspiracies?

Gharbeia: They’ve used it the whole of my political life, which is all of seven years. It was used to discredit the Kifaya movement in 2004 and 2005, and the 6th of April Movement more recently. Today, the same groups and individuals who were targeted back then remain targeted now — which tells you really how much of a “transition” this has been.

Wells: We’ve been harassed since the moment we opened up. At some point Al Qahira newspaper, which is a cultural weekly published by the government, accused us of taking money from Israel to carry out our projects. It’s the same narrative of people having taken Kentucky Fried Chicken during the revolution to burn tires in Tahrir Square. And you know, other people who have tried to open arts spaces, especially foreigners, in Cairo or Luxor, have been shut down because of these accusations. If you opened up a space that wasn’t in line with the powers that be, they would delegitimize you with calls of foreign agendas. It’s never been easy.

Angela Harutyunyan: Or take the occasion of the Egyptian Pavilion at the last Venice Biennale. The pavilion included the work of Ahmed Bassiouny, who lost his life in the revolution. It was organized by his friend and colleague Shady El Noshokaty, who teaches at the American University in Cairo. At a press conference for the pavilion, Shady was accused of receiving “American funds” by a government official who on the one hand created bureaucratic obstacles for the realization of the project, and on the other hand made sure to distribute Tahrir stickers at the opening of the pavilion in Venice. You see a lot of this playing out in local cultural politics. In this case, Shady had received a travel bursary from the American University as well as equipment to display the work. The government didn’t provide enough funding for the execution of the pavilion, but also accused Noshokaty of accepting “foreign” funds.

Moukhtar Kocache: The government creates this atmosphere over and over again to allow them more control over civil society. They take advantage of a mostly old-school leftist fear of foreign funding, which had its moment in the eighties and nineties, mingled with standard Arab fears of intervention and imperialism.

How many times have you been called a foreign agent?

Hossam El Hamalawy: I’m a member of the Revolutionary Socialists, and they’ve gone so far as to accuse me of being a CIA agent, if you can believe it. Here is the biggest client of America using the US card as a weapon against its enemies. The biggest recipient of foreign funding in Egypt is the Egyptian government, and the most corrupt entity within it is the military. These are the guys that receive $1.3 billion in US aid per year and control a business empire that covers twenty-five to forty percent of our economy, producing everything from pasta to mineral water to missiles. They should be investigated before anyone else.

Alaa Abd El Fattah: I’ve been accused of being a foreign agent millions of times. But that doesn’t work so well with me. People don’t buy it. So they call me gay. Or since that doesn’t work, a gay-rights supporter. I’ve been called an atheist, too. As funders have you encountered resistance? Kocache In the eight years I spent in the region it would come up in public forums and conversations, and in the press now and then, but by the end of my tenure it had mostly disappeared. People have become more sophisticated, more knowledgeable about the diversity of the funding matrix and what it’s there to do. Money doesn’t always come from foreign governments; it comes from foundations, agencies, ministries of foreign affairs… People may feel there are foreign agendas or that some institutions have a poor understanding of the region, but in large part they no longer believe the conspiracy theories.

Basma El Husseiny: It’s true, there’s been huge improvement. Today there are only a few organizations that hold out against foreign funding and the criticism is much less than say three or four years ago. You find people today explicitly saying that without foreign funding we wouldn’t have such a vibrant arts and culture scene. The criticism is limited to a few people from a much older generation who tend to stick to a limited nationalistic discourse. Still, if you ask the average person on the street about all this, they will be critical because they’ve been taught through the media that foreign funding means foreign meddling.

Civil society groups, whether human rights groups or even arts spaces, tend to exist in legal limbo in Egypt… . How has that played out?

Gharbeia: This is the crux of it: the fact is that most activities in Egypt are illegal but tolerated. Like the fact that five people standing together on a corner violates a law that goes back to 1914 and British attempts to halt the nationalist movement. In this day and age, we have articles in our draconian penal code criminalizing labor organizing, and these articles were taken from no less than Mussolini. It’s the same with the existing NGO law. Most independent human-rights groups wouldn’t register under the existing law because it’s very restrictive, so they tend to exist as nonprofit companies. The organization I now work for, EIPR, was denied registration once, we fought it in court, and then we were denied again.

Marwa Sharafeldin: Under Mubarak, to set up an NGO you had to get permission from State Security. We would go to the Ministry of Social Affairs, and it in turn would then send our files to State Security for approval. Whenever we would apply for something, or were waiting for approval of funds, we’d go to the Ministry, and the answer would almost inevitably be, “it’s still with security.” They create a system that’s impossible to deal with because it’s so twisted.

Wells: It’s true, even those organizations that manage to get NGO registration have found that this brings on even more restrictions. Every grant has to be held at the Ministry and reviewed, and the process could go on forever.

Do you think there’s a real fear of civil society groups from those directing this crackdown?

Abd El Fattah: Fayza [Abou El Naga] has publicly talked about how the human-rights sector played a role in bringing about the revolution. This is a pretty correct assessment, though she probably can’t tell the difference between the radical rights activists and the charlatans. The regime is consistently trying to dismantle and cripple anything that played a role in the events, be it individual activists, independent media, Internet kids, football ultras, human-rights groups, the 6th of April Movement, et cetera. Also remember that the current controversy isn’t as much about funding as much as it is about applying for funding without getting permission from security. Or establishing an NGO without complying with the draconian NGO law. It’s about the freedom to organize, not about funding. Funding is just the excuse they use in the media.

El Hamalawy: NGOs like the Nadim Center and the Hisham Mubarak Center — both of which incidentally refuse US funding and were founded by former communists — played a central role in helping the street movement after 2000 and getting us where we are today. They were key in mobilizing the Palestinian solidarity movement, too. And later, both NGOs were central to getting legal support for striking workers and victims of police torture. If that means there’s reason to be afraid of them, then yes.

Sharafeldin: The attacks at the moment seem to be on the very NGOs that stand to monitor the Egyptian government. From this crackdown you can see that funding for these types of NGOs will never come from the government. This is an attempt to paralyze them completely by playing on nationalist sentiment and xenophobic fears.

There are allegations that a lot of money was dumped into the country after the revolution, most of it unregulated.

Sarah Rifky: That’s inevitable, I guess. There were a lot of grants with the usual, predictable key words: democracy, crisis, new social order, new social politics, youth, youth, youth, youth. There were two types of responses to this: those who really milk it, and those that push back. There are concrete examples of the push back, as when the Berlin Biennale curatorial team wanted to do research in Egypt. I think their open call came just after the Tunisian Revolution. Talk about bad timing.

Oussama Rifahi: Since the Arab uprisings, AFAC has had additional funding to make available to the public. We came up with two programs. One involved a quick reaction to the uprising, an “express program.” It ended up ruffling feathers.

How so?

Rifahi: There were questions raised: how could you react so quickly? In fact, we ended up giving a lot fewer grants than originally expected; quality was an issue. But I think the conversation was dogmatic and even out of touch with some of the realities of what artists needed. I think of Doa Aly’s essay, “There’s No Time for No Art” as a reference.

Khaled El Qazzaz: You know it was announced that over $100 million was sent to Egypt after the revolution. The question for me is, where did this money go? It’s an alarming number. We have a broken NGO law and urgently need legislation that regulates NGOs and allows them to be active, as long as their activities are transparent.

Doesn’t a lot of that money go back to where it came from?

Sharafeldin: Yes, absolutely. You have to remember that a lot of these funds are self-serving. Some donors give money to NGOs on the condition that they work on very specific issues that fit into their agendas, or on condition that they buy equipment — like computers, for example — from the donor state. Someone told me that for every dollar that comes to us as foreign aid from the US, ninety-five percent of it goes back because of the conditions attached. Canadian aid isn’t that different. Apparently on their website they have a sort of transparency that says something like, “Hey taxpayers, the money we give in aid comes back to you again…”

Abd El Fattah: It’s been much easier to fundraise since the revolution, especially since nobody bothers with the law. But since the judiciary is slowly siding with the bloody state, that will change soon. They’ve already arrested people for providing sandwiches to protesters, calling it material aid to rioters.

Unregulated foreign sandwiches!

Abd El Fattah: These are veiled middle-class moms who go to local sporting clubs distributing sandwiches…

Where do you draw lines when it comes to funding, or do you?

Wells: Me, personally, not at all, but for the sake of the gallery I have red lines that come and go. Take, for example, any money affiliated to Israel — for all sorts of reasons. At the moment I wouldn’t touch the American Embassy. In a different situation, I would so long as they didn’t impose any restrictions. It has to do with the mood of the landscape at the moment. They are offering so much money to so many people, but I wouldn’t touch it.

El Husseiny: At Mawred, we don’t receive State Department funding or governmental American funding, but we welcome private American funding. The agendas of many American private foundations are close to our agenda, while the State Department has an agenda we can’t support.

Is it tenable to say “no” completely to any and all external funds?

El Husseiny: How could we? The portion of civil society concerned with human rights, civil liberties, environment, and arts and culture is like ninety-five percent dependent on foreign funding, so if we were to prosecute everyone who is implicated, the number to be prosecuted would be in the thousands, or hundreds at least.

Rifky: It would be naive to say no. There’s no money in our economy generally that is “pure” politically speaking, and in the case of the arts, much less. Receiving foreign money doesn’t mean you’re complicit. The Egyptian state borrows money from the army and the army from the US. It would be bizarre to then say someone is guilty for taking Belgian money. Where the money comes from and moves to is so opaque. The debate also reminds me of [the lawyer] Amr Shalakany’s argument regarding the political naiveté of the Israeli boycott. Refusing to enter Israel means that you’ll never be able to visit Palestine or develop a real rather than imagined relationship with the Palestinian people.

El Hamalawy: I’m against all foreign funding. Absolutely. But I do respect the intentions and actions of many NGOs that receive these funds. I’ve personally worked with many NGOs who take foreign funding, so I can’t take a sectarian position, but for those in bed with the Americans in particular, I have many reservations.

Issandr El Amrani: It’s only possible to cut foreign funding if Egyptians start funding organizations themselves…

El Qazzaz: A vast amount of money left our country with the revolution, mostly with people from the previous regime. We have a huge cash flow problem because people are hesitant to invest or spend money in general. I think western countries in general, especially the ones that supported the previous regime, have a responsibility to the people of Egypt. We need immediate help, but this help shouldn’t come with intervention in our internal politics.

Does true “independence” exist?

Harutyunyan: There’s no such thing as independence. We’re all complicit in one way or another. The notion of being independent is often used to present oneself as a heroic victim of circumstance.

What of the gesture? Is there any value to the gesture of saying “no”?

Rifky: The gesture is not productive. It would be more productive to try and radically rethink the infrastructural questions related to arts funding and try to generate new ways of supporting the arts.

But there must be some forms of fundraising that are sanctioned?

El Husseiny: It depends on what you want to do. If you want to do charity work, like working with street children or other straightforward charity causes, you could find local funding. But if you want to touch human-rights activism, civic education, or any kind or arts and culture and media advocacy or reform, there’s no chance you’ll find local funding. You might find small donors, but for the most part they will want to be invisible. The people who have money don’t want to be associated with big change at any level. Even now, after the revolution.

Gharbeia: The field and the practice of fundraising don’t really exist in Egypt. Our closest experts on fundraising are the people who fundraise for Islamic charities. The alternative for civil society organizations is appealing to the government and, guess what, they’re usually the main target of work that a lot of NGOs do.

Abd El Fattah: The reason we’re so dependent on donor funding is limitations set on collecting donations. There’s also pressure on rich businessmen who’ve opted to fund such activities in the past. Since the homegrown charity replaces the nonexistent social security net, we won’t be able to cultivate a full replacement for donor funding at the moment. We’ll have to either depend on the state or big business, and both are not good for independence, so a mix of sources is best. The serious radical centers have multiple sources of funding, severely underpay their employees, have strict policies of wage discrepancies and spend most of their money on travel or legal fees.

How did the association between NGOs and foreign agendas come about in the first place?

El Hamalawy: If you go back in time and look at when the NGO movement began mushrooming — it was back in the 1990s — most of the founders of the sector were communists. They were disillusioned by the collapse of the Soviet Union. At the time there was no social movement left, and all you had was right-wing Islamic insurgency in a fight with the government. As a result, a lot of the secular intelligentsia sided with the state. Initially they had a bad reputation and were regarded by radicals as sellouts even if they didn’t take money from the US government… Then other leftists started NGOs, most of which got their funding from western countries. Some took and continue to take a stand against American money in particular — and though I consider this decision trivial, personally, it’s definitely the most corrupt NGOs that went for the American money. In the 1990s we described those NGOs as the “human rights boutiques.” They would issue occasional reports in English to feed their donors so they could get more money…

So who are the institutional holdouts against foreign funding?

Kocache: Surprisingly or not surprisingly, the groups that have maintained the most entrenched anti-foreign funding views tend to be the groups that hover around the government. These are people who work in semiofficial NGOs or the government-created NGOs or the cluster of individuals who benefit from government services and perks. And they’re mostly marginal.

Wells: It’s also a generational issue. I remember the first Nitaq Festival, which was an arts event held in spaces downtown. That first year, Basma, who was at Ford, offered us $85,000 for the festival, but no one from the older generation would take part. We ended up approaching younger artists who had no problem with it and everything went fine. Those refusing to participate were major players who reject any foreign affiliation whatsoever — many of them are involved in theater and music — and they will never back away from this.

Abd El Fattah: There’s always been a spectrum of positions not only per group but also per situation, from the Revolutionary Socialists who abhor all forms of funding to others who subsist on it. Don’t forget that many activities are done without donor funding at all.

Like what?

Abd El Fattah: Like material support for prisoners or for workers on strike. Food, clothing, medical support. There’s also pure campaign work, like the work of the anti-torture umbrella group or the Front to Defend Egyptian Protesters.

What effect is the current crackdown having?

El Husseiny: It’s intimidating a lot of people. It’s threatening small NGOs that might have been contemplating applying for funding from outside the country and might not do so now. It’s also intimidating the well-established NGOs who haven’t been touched by the campaign yet, but who might want to stay below the radar. I think the real purpose of all this is intimidating the donors themselves, to say: “We could prosecute these people. You’re endangering them…”

Wells: I am about to find out. I recently had a meeting with partner organizations — basically Townhouse, CIC, ACAF, MASS Alexandria — and we’re trying to map out alternative ways to raise money from the region. This is obviously something that we’re looking into quite closely because of what is happening…

Have donors reacted?

Wells: For the most part, they’re more careful. A lot of organizations, for example, won’t insist that we put their logos on fliers anymore.

Have you ever gotten in trouble for a logo?

Wells: Only the US Embassy, but it was actually my other funders who called me and said, “Remove that!” But yes, they are very insistent on their logos being placed on any project they fund. Logos are paramount to them.

Do you worry about the abundance of money and how it’s being used or abused?

Wells: I worry about some of the younger initiatives and emerging artists, because they lack experience and skill and might sign on to grants and projects and not realize the consequences down the line. On the part of the grant makers, this reflects a lack of sensitivity to people on the ground.

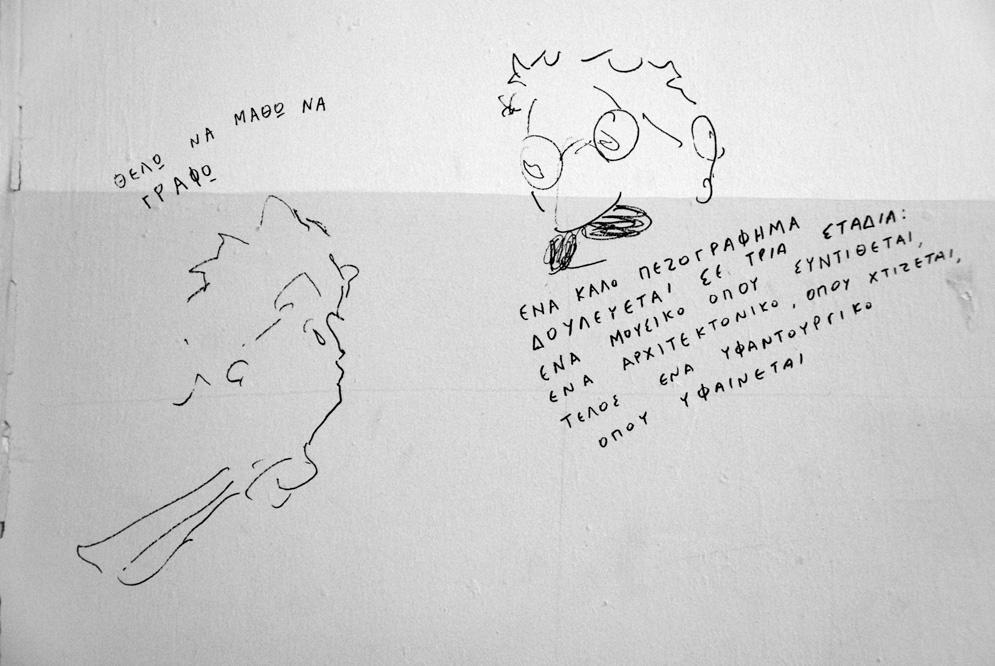

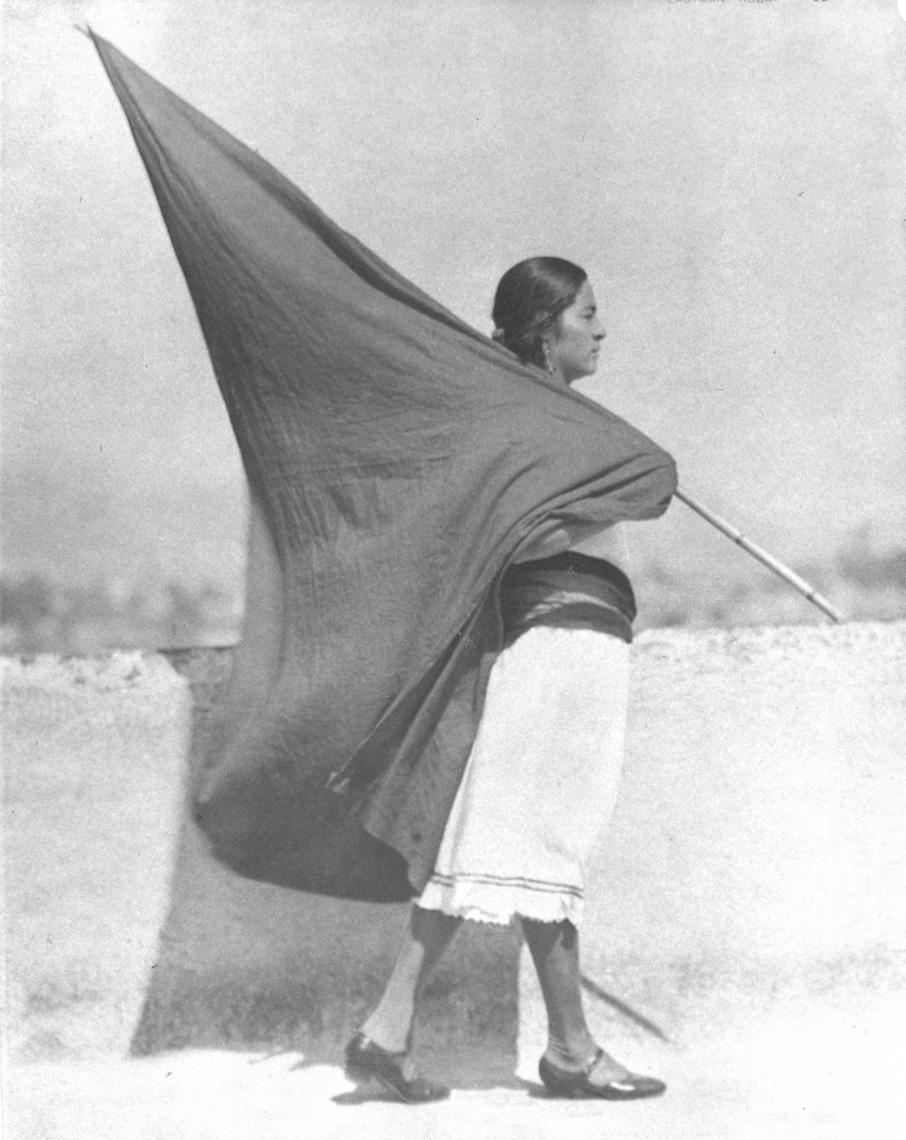

Harutyunyan: It’s also affecting the kind of art that’s being produced. In postrevolutionary Egypt — or I should say, in revolutionary Egypt — there’s great demand for fossilized monumental representations. You can see certain genres of revolutionary art — like paintings of the revolution in the form of graffiti. I find this problematic, the monumentalization and representation of something that is ongoing… How is it possible to paint a revolution?

Is there a way for artists to productively push back?

Harutyunyan: There is “resistance.” But when I talk about resistance I don’t mean active resistance and false claims to being independent, but rather carrying out an autonomous practice. These are artists who are engaged with their own practices, who aren’t willing to succumb to the hype surrounding the revolution, and who don’t give in to producing iconic or representational work.

What have you done historically to try to deflect easy attacks of foreign conspiracy?

Wells: Years ago we were really dismissed as foreign by the Ministry of Culture and official state organs. We couldn’t even hang Townhouse posters at the state schools to invite students to come to our exhibitions. So we started a student council, and by actively offering a space to people who didn’t like the gallery, offering to produce a show or a book, we won a lot of people over and diffused the perception that were outsiders. I think [the artist] Malak Helmy — she was part of the council — once said to me that there was no way in the social world of Cairo that such a mix of students would meet and share studios. We won them over.

What about as a funder, what do you do to give smartly?

Rifahi: We’re an Arab fund. Our pot is made up of international and regional funds. This is the intelligent thing to do — an in-between. The pot is independent, and when we give a grant to an artist in Egypt, for example, it’s a mix drawn from international, regional, and local sources.

Rifky: I’m not entirely convinced of that approach. It feels a little like a money laundering operation. The foundation is acting as a middleman or dealer for other funds. A portion of AFAC’s money comes from the Open Society Institute, for example…

Let’s talk about donor agendas.

El Amrani: There is clearly an overt agenda by governments and foundations that spend this money: they want to spread a culture of human rights, they have concerns about minorities, etc. The rise of human-rights culture is not entirely innocent. It has its roots in the late Cold War, the Helsinki Accords, and so forth. But the Egyptian government itself has signed on to plenty of agreements and accords. Funnily, the US Embassy recently hit back with a primer on how NGOs work in the US, noting that they can accept foreign funding, too…

El Hamalawy: At the moment, they’re obsessed with elections as a marker for democracy. It’s no secret that the National Endowment for Democracy was charged with very nasty interventions in both Palestine and Latin America. These funders are not innocent.

Do the grant themes influence the form projects take?

El Husseiny: Of course. This happens both consciously and subconsciously. It’s a global thing, not specific to Egypt. If you know there’s money available for women’s issues and your project involves women at some level, you might try to emphasize that aspect. Fund seekers must stay focused on what they really want to do.

Wells: I would apply to a cultural department with a grant, and I would find myself in a meeting with civil society and human-rights organizations. As soon as you use the phrase “freedom of expression,” you get the grant. In the past, the key words may have been drawn from the development or, say, gender world… there are cycles.

What about subversion, taking money and running with it?

Rifky: For me it’s not about subverting. It’s a question of being given autonomy and time. These projects need time to gestate.

How has the uprising influenced the perception of artists, if at all, vis-à-vis the nation?

El Husseiny: The arts have gained a lot of credibility given what has come to pass in Tahrir. We’re in a strong position, and now it’s up to the artists to build on that.

What next?

Gharbeia: Society is opening up. There will necessarily be a lot of public money floating around — for the election campaigns, people trying to organize charities, cooperatives, etc. We need to invent a number of legal forms of organizations and fix others so that all the activity that is buzzing around could find ways to organize.

Sharafeldin: We need to be a bit more complex in how we look at this issue, how we address it, how we react. We are active citizens and we have rights, like the right to associate. And yes, they have the right to audit. Corruption does happen, of course, and some funds are being used the wrong way — no one can deny that. So yes, there needs to be monitoring, but the system of monitoring needs to change, and the questions the government is asking need to change.

El Husseiny: Frankly, I don’t think people believe this bullshit at all. I think people will speak against it soon…

Rifahi: We’re hoping to raise more local funds. If we manage to move from fifteen local donors to thirty in one year, that would be fantastic. These are the first steps for philanthropy in the region.

Wells: We’re unbelievably busy. Everyone is offering money. We’ve received three proposals in the past four days to partner with institutions on a major EU grant — just this week alone. It has, you know, the language of “building bridges across the Mediterranean.”

Will you go for it?

Wells: Probably. As long as there are no strings attached.