“Darling, I’ve bought you some crack,” purrs Loreta, striding in my front door. “From Satwa.” The crack in question is actually Krack, an antiseptic cream for sore heels, purchased from an area of Dubai known for its bargain basement outlets full of Burberry and Tods, besides the odd illegal substance. To our next meeting, the six-foot-something artist and sometime catwalk model brought a box of Forever Rosemary, the well known “ambassador’s chocolates.”

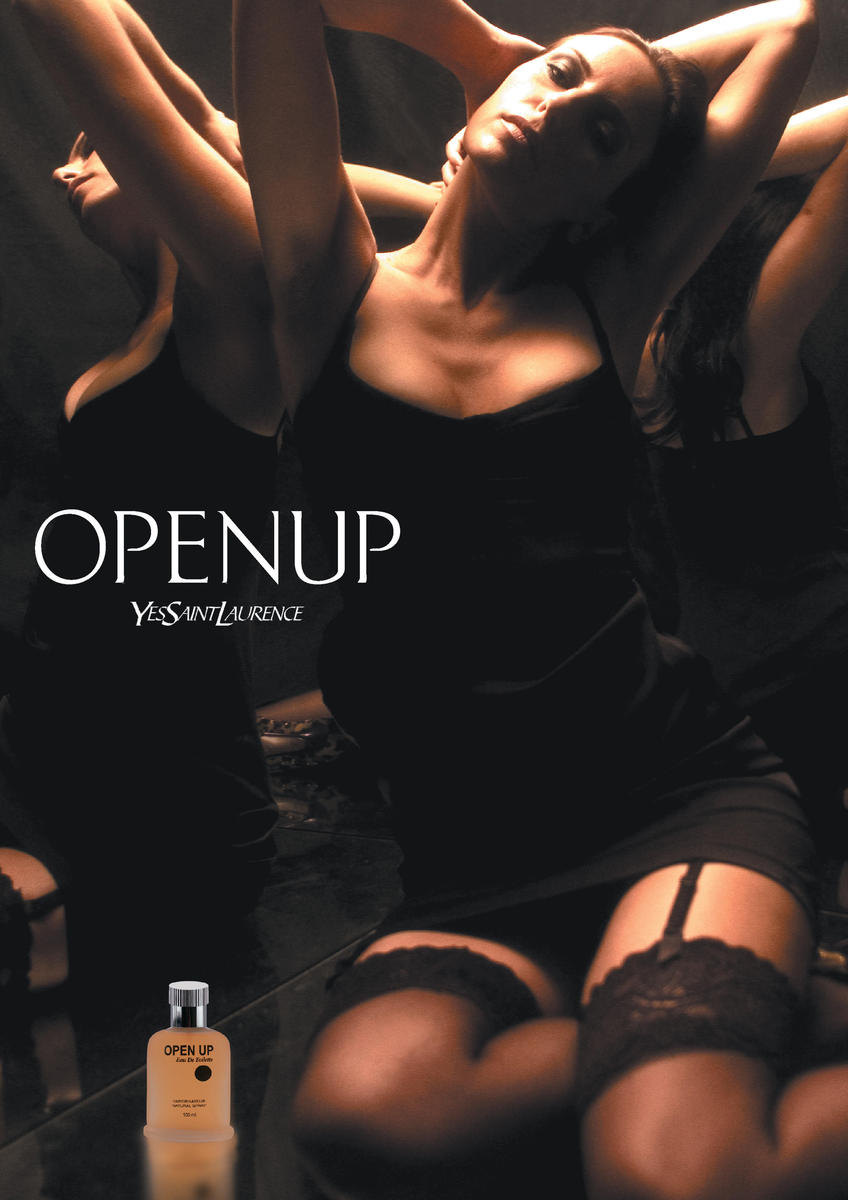

Born in Lithuania, Loreta Bilinskaite-Burke began learning English at the age of nineteen; with the ear of the polyglot, she delights in the creative use of the language by the South Asian traders that rule deluxe Dubai’s reality-check neighborhoods. In a land not known for its developed sense of irony, Loreta’s inventive, tongue-in-cheek art practice is refreshing. (In another persona, she fronts a weekly style program on Dubai’s national radio, discussing the delights of Obscurity perfume, Your Boss and Polite aftershaves, Manly Man from Titanic eau de cologne and so on. Her latest series of work, in part commissioned by Bidoun, sees the artist direct and model for a series of “advertisements,” with all clothes and accessories sourced from Satwa, in a wink at the branding of desire.) She plucks her influences from the most unlikely sources — this in a place where most artists turn their backs on the urban experience, preferring nostalgic pastoral scenes of the desert and imagined times gone by.

For Dubai’s first public art project — a parade of camels that mimicked similar ventures with cows in New York, London, and elsewhere — Loreta collaborated with mosaic artist Jenjira Prasertsin to produce Dubai Dream. Amid a herd of illustrated models, it rose above the cheesiness of the project to actually say something about the city. Covered entirely in a mosaic of rough-cut “diamonds,” Loreta’s sculpture is seductive; sold for 250,000 dirhams (68,500 US Dollars), it is a particularly well-appointed camel, and no doubt broke some world records. Yet we know that the sculpture is fake — created in mirrored glass rather than diamonds. It represents the Dubai dream — from the coveted jewels that fed the trade port’s rise to power to today’s celebration of corporate capitalism. But on closer inspection, the mosaic simply reflects viewers back at themselves. The mirror image is fractured, distorted. Is this the ultimate in kitsch or a thing of great allure? Once again, the Dubai dream has you foxed. Loreta has plans to continue her exploration of the city’s predilection for flash; a current project involves covering a sports car in tiny mirror tiles.

Loreta moved to Dubai only two years ago, yet her practice is arguably representative of the transient city. She takes a sharp yet not wholly cynical eye to Arabia’s land of dreams. Her work dwells on her adopted home’s service culture: Playing with the futuristic city’s reliance on imported labor, she commissions South Asian garment factory workers to produce art for her. One such “manufactured painting” features a white canvas patterned with a concentric eddy of black sequins. “I asked them for a beginning and an explosion,” explains Loreta. “It’s their interpretation. At first, they didn’t want to work off-pattern. But this ‘Madam,’ ‘Sir’ culture is new for me, and I wanted to test it out — in a reverse of the Dubai dream, I’m paying people to have an opinion.” She riffs on a favorite subject: the similarities in practical terms between communism, as she experienced it in Lithuania, and capitalism, as manifested in extreme form in the UAE. “In the end, everyone wears the same, expresses themselves through the same possessions, and is paid not to think.”

Atelier Loreta is a flat overlooking a featureless, inner-city landscape of square towers broken by intermittent scrubby patches of sand. The walls currently feature a series of land- and seascapes on canvas. Inspired in part by the UAE censorship department’s habit of shading or scribbling over offending words, phone numbers, and images in imported magazines and newspapers, she has blocked out notes written along the horizon with simple rectangles of red hand-rolled glass.

Before moving to Dubai, Loreta lived in London and worked predominantly in embroidery and installation, although her interest in needlework lies more in her Lithuanian roots than any Tracey Emin–esque affectation. “At home, everyone can sew,” she assures me. Supporting herself through art college by working as an international catwalk model, she spent hours each week at various embassies, queuing for visas. As an Eastern European, she had to renew her UK visa each month. Every visa became “like an award.” Appropriately, she began silk-screen-printing the badges of admittance onto prized Lithuanian tablecloths — “something you reserve for special guests” — and embroidering letters and symbols in gold and silver thread. “Indefinite period,” “Leave to remain,” “Marriage Single Entry,” are picked out in ironically reverential and lovingly sewed threads.

She professes to be more interested in the process of making rather than the show of exhibiting, as illustrated by video works that she shows alongside major projects. Words (2003) is a collection of rosettes, each carrying an embroidered word, taken randomly from tabloid front-page headlines. Contrasting her life in London with the “medialess existence” of some of her rural relatives in Lithuania, she has created a series of trophy-like tapestries. The “fifteen minutes” of each subject, each headline conjured up by subeditors working to deadline, is painstakingly created in the most time-consuming method. In the accompanying video, Loreta sews everywhere: in London, on the bus, the tube and shuffling along on a protest march against the war in Iraq; at catwalk shows, in makeup; as a “flower pot” (decorative guest) at a fluffy corporate function; dressed as an airhostess for an Emirates airline shoot, sitting in a crowded square in Marrakech. “Kylie,” “Bin Laden,” “clone,” “ripper,” gradually take shape, created in a kind of performance. As an installation, the work plays with the viewer’s perceptions: Anxiously, the mind’s eye tries to connect the arbitrary words, to create sensational sentences.

Loreta’s work in embroidery came to a head with Worship, a vast tapestry featuring footballer David Beckham in a pose that mirrors icons of saints in her local church in Lithuania. Made with the same stitch used in the Bayeaux Tapestry, using gold and silver thread, the work was completed over three months, mostly in Lithuania one long summer. From that season’s spiky haircut, to his gold Adidas shoes, Becks was created in minute accuracy. It was, says Loreta, an explicit effort to immortalize his universal yet disposable fame in infinitesimal, laborious detail — in effect, to materialize time. His fame, following the 2002 FIFA World Cup, was all-consuming; his persona alternately glorified and vilified by a media well-versed in Bushist polarities of “good” and “evil.”

Once again, “the Beckham,” as Loreta likes to refer to it, was a peripatetic work: The accompanying video shows the British icon taking shape at picnics, by the beach, in the family’s summer house, in a concrete landscape in Vilnius. It became, as she documents, a social event, with friends and relatives coming from afar to spend a day stitching and chatting. In a way, Loreta’s documentation of the summer of Beckham is a paean to changing times. Harkening back to her own childhood, she captures Russian cartoons on television. The older generation — those who still live a simple country life, fetching water from the well, living on dry bread in the winter — had no idea who they were creating, but the post-post-Gorbachev youth act all “homeboy” for her camera, lip-synching perfectly to rap and talking knowledgeably about Becks’s latest performance.

Her portrayal of her family is warm, but not purely innocent. Shown alongside Worship at Central St Martin’s College and then (ironically enough) at Victoria House in London, the video prompted gallery visitors to ask Loreta questions such as “Where did you get these people from?” This perhaps says as much about the service culture of contemporary art practice as it does ignorance within Europe.

Loreta’s relationship with her home country is complex, yet she has no truck with the anguish of displacement as expressed through traditional identity politics. A documentary style series of portraits of old women, taken each summer on her return, is a bald attempt to capture slipping time. “I am a part of it, every time I go back. But equally I’m at home elsewhere in the world.” One moment in the Beckham video captures her relationship with her home country: Relatives and friends, all staying at the family summer house in an idyllic, Hansel-and-Gretel forest, dress up in their oldest “country clothes” and mug as models, prancing down the catwalk of the garden path, with Loreta forced to sit in the “front row.” “They do this every year,” she sighs. “It’s kind of taking the piss.”