Naeem Mohaiemen has just been nominated for the 2018 Turner Prize and, as the sun pours in on a blazing hot afternoon in Mumbai, I am staring at a news piece in the Guardian that describes “a more overtly political [list] than in previous years, featuring artists tackling issues of post-colonialism and migration, queer identity, human-rights abuses and racial violence.” I put it to Mohaiemen that watching historically white institutions scramble to remain relevant with showy displays of “solidarity” and “good politics” makes for a messily implausible spectacle. We are speaking over Skype, and Mohaiemen, who is sat at his desk at home in New York, is wrapped in a blanket and sipping a green smoothie. “Today we may have anxieties about how political work is being seen,” he replies, “or concerns about how non-white bodies are being seen. But fifteen years ago, whiteness dominated the art world in a way that we felt it wasn’t for us. In 2004 the Iraq and Afghan wars were raging and you would walk into an American museum and there was no sign that the country was fighting two wars oversees. It was brutally alienating. I know that the art world ‘correction’ can be very strange sometimes, but I much prefer the correction.”

It is early morning in New York. Late April, but still wintery. Mohaiemen is elegant, his hair slightly tousled. As he speaks he moves in and out of the camera, leaning his head lightly to one side. I am struck by his generosity and by his indirect approach he takes when discussing his work. Mohaiemen sets off on tangents, moving deftly between anecdote, event, and analysis, always totally animated. He is fond of the phrase, “the thing I keep circling around,” and circling is exactly right. Like a kite catching thermal wind, he swoops over dense histories to draw out broad patterns.

In the media frenzy around the Turner Prize nominations, several publications referred to him as a “British artist.” The Daily Star, a Bangladeshi newspaper that has published Mohaiemen for many years, described him as an “expatriate Bangladeshi.” Neither description is right, exactly. He was born in London, where his father was studying medicine; the family returned to Dhaka, then part of East Pakistan, while he was still an infant. He has lived in the US off and on for nearly three decades. Today Mohaiemen divides his time between Dhaka and New York.

Mohaiemen came to the US in 1989, the year the Berlin Wall fell. He did a degree in economics at Oberlin College, where he participated in the campus activisms of the era. In 1996, he joined the editorial collective SAMAR (South Asian Magazine for Action and Reflection), a pioneering progressive journal based in New York. The small team of editors and contributors would carry boxes of the magazine to sell at South Asian events around town, celebrating when they had fewer copies to lug back home. The members of the SAMAR collective, whether Indian, Pakistani, or Bangladeshi were united in their opposition to right-wing politics, particularly Hindutva, which was already a major concern in the diaspora. Many of their conversations revolved around how to keep the BJP out of power. “We did not see what was to come,” Mohaiemen tells me quietly. “But maybe nobody did.”

After September 11, 2001, “Muslim” became a racialized identity. Mohaiemen began moving with groups like the New York Taxi Workers Alliance, Youth Solidarity Summer, 3rd i South Asian Film, and the collective behind the club night Mutiny. In 2005, the Queens Museum presented Fatal Love: South Asian American Art Now. Mohaiemen participated as part of a group of activists, lawyers, filmmakers, and photographers who called themselves Visible Collective. His work with Visible Collective marked a turning point. “For years, the only two topics from Bangladesh that you could work on — and that there was funding for — were climate change and the refugee crisis,” he says. “The show at the Queens Museum was the first time I was working on something that wasn’t about back home.”

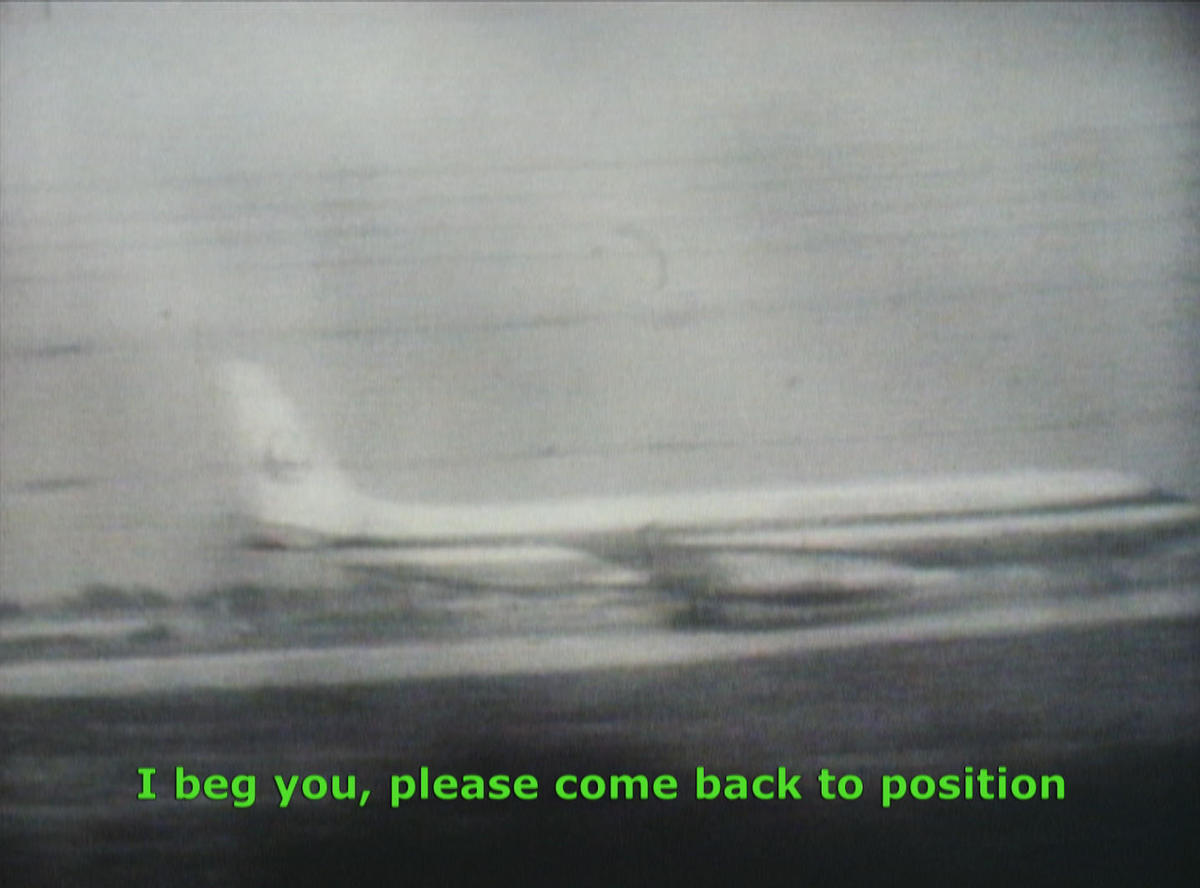

A lot of this work involved advocacy, and many consider these to be Mohaiemen’s “activist years.” He visibly shudders when I ask how his activism and art practice overlap. “I feel that the word “activist” is still attached to a positive value judgment, and I’d rather leave that to the side,” he says. The remark is characteristic of Mohaiemen’s distrust of definitions; he prefers to keep things ambiguous. This quality is evident throughout the work. Mohaiemen is not interested in presenting neat narratives; his work suggests a notion of history as untidy, and marked by the incidental. “I feel like the films I make are about the sort of thing that you would find in the footnotes to an essay. Like, by the way, in 1977, there was a plane hijacking that happened against the backdrop of a Maoist coup, although the Maoist coup was the main tendency in Bangladesh at that time.” Mohaiemen is referring to United Red Army (2011), which depicts the events of late September 1977, when Japanese Airlines Flight 472 made an off-course descent toward Dhaka Airport. News broke that the flight had been hijacked by the Japanese Red Army, a high-profile group of revolutionary communists who had seized the plane in a show of solidarity with the Palestinian cause. And as plane hit tarmac, three nation states were flung into a ring together.

In grainy CCTV footage, we see the control tower at Dhaka airport flooded with officials, including Air Force chief A. G. Mahmud, in charge of negotiating with the hijackers. Neither party knows enough about the other. The JRA believes that Bangladesh is an independent socialist state, when in fact it is a military government that came to power in a coup against a leftist government. The Bangladeshis know little about the group’s violent reputation, their penchant for brutal executions — of their own comrades, as well as hostages. As the film progresses, we listen in on fragments of conversations between Mahmud and the spokesperson for the hijackers, who goes by the codename Dankesu, over the course of five days. In the film, a transcript is overlaid onto the recorded conversation, the voices identified by color. Mohaiemen’s edits reveal the innate humor and idiosyncrasy of the stuttering dialogue: being privy to the footage feels like being let into a secret.

Mohaiemen’s films rarely present us with plot twists or definitive images; he prefers to unroll the whole contact sheet: the succession of small and overlooked moments that subtend the larger events of history. The films can be seen as essays, but Mohaiemen insists that they allow him to move beyond the bounds of the essay format. Moving-image work helps him access a subconscious. “Filmmaking for me is often a departure, a flight away from the specifics,” he says. His most recent work is in fact a piece of fiction. Tripoli Cancelled (2017) premiered at the Athens edition of documenta 14. A ninety-three-minute feature in which a solitary man drifts through an empty, abandoned modernist airport.

The film is perversely slow. The man reads aloud from letters to his wife, or from one of his only possessions, a copy of Watership Down, his son’s favorite book. He plays out elaborate fantasies. In an airport bar he chides the imaginary bartender for forgetting that as a “Muselmann,” he prefers soft drinks; in the pilot’s chair of an idle helicopter he puffs his mouth like he is smoking a cigar — chug chug chug — before taking the chopper for an imaginary ride. The camera pans across the deserted landscape, both inside the airport’s interior as well as its exterior facades, with broad sweeping angles, its movement mimicking the pace of the film. “Toward the end of each scene, the crew would all be looking at me, expecting me to say cut,” Mohaiemen tells me, “but I shake my head — no— keep going.” Slowness is used as a formal device, a deliberate act of stretching time, testing the limits of our patience. It also intimates the experience of the protagonist, alone in the airport for 3,753 days.

The protagonist’s musings are full of small citations. Muselmann is an old German word for Muslim; it is also the title of a chapter in Giorgio Agamben’s Remnants of Auschwitz, an enquiry into the testimonies of those who survived. In the book, Agamben explains that Muselmann was a slur directed at prisoners who seemed to have given up completely, who were seen as exhibiting no will to survive. Another segment refers to “our philosopher friend” who is on assignment covering the trial of “the mass murderer” — a reference to Hannah Arendt’s Eichmann in Jerusalem, with its infamous discussion of the banality of evil. “We are the lines of control,” the protagonist of Tripoli Cancelled reflects. People do terrible things in order to belong. He does not exempt himself as he writes to his wife, “I know that if ever I was cruel, you would not sit quietly.”

Then there is the airport itself. Designed in part by Eero Saarinen, the Ellinikon International Airport in Athens was closed in 2011, and in recent years refugees had set up informal camps in its halls. For Mohaiemen, it was a site of family history as well: his father was trapped there for seven days in 1977, after losing his passport en route to Tripoli.

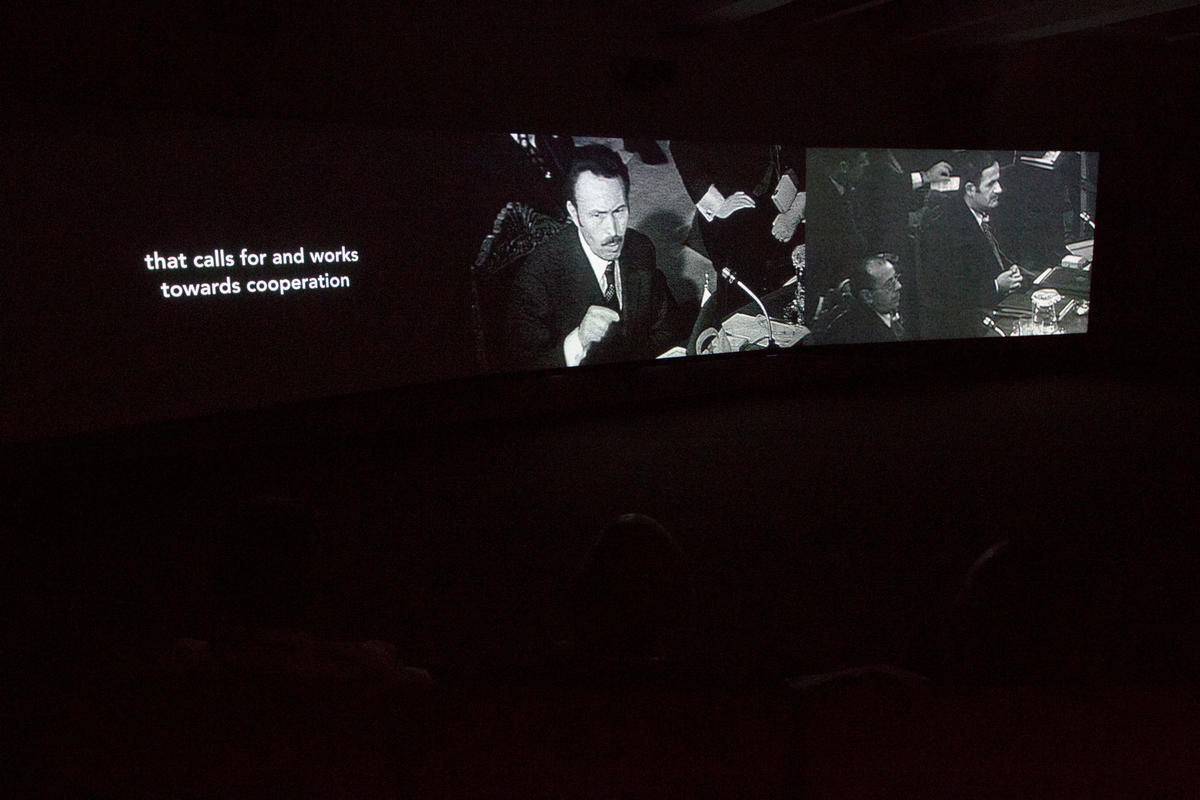

At the Kassel leg of documenta 14, Mohaiemen premiered Two Meetings and a Funeral (2017), a return to nonfiction. Making extensive use of archival footage, Mohaiemen presents a dashing cast of youthful political players — celebrity leaders of independence movements across the world, including Muammar Gaddafi, Yasser Arafat, Indira Gandhi, Fidel Castro, and Bangladesh’s own Sheikh Mujibur Rahman, among others. Two Meetings speaks to Bangladesh’s trajectory as part of the Non-Aligned Movement (NAM), in which formerly colonized nations (some of them still colonized) came together to devise a union to rival the Western bloc and the Soviet Union. The film’s first meeting is the 1973 NAM summit in Algiers, to which the new nation of Bangladesh arrives still convinced of finding a secular, socialist path. The second meeting, which takes place the following year in Pakistan, sees Bangladesh reluctantly aligning with the Organization of Islamic Cooperation — a Saudi-led coalition of Muslim countries. Two Meetings is tugged by an undercurrent of longing for this lost moment, and for a future that might have been. “I say what I do is a critique imbricated with love for this movement,” Mohaiemen notes. “But it is not naive. The story is tragic, but it’s more Shakespearean than Greek. Failure was not inevitable.”

Failure is a recurring motif in Mohaiemen’s work. The Young Man Was is a series of films completed between 2006 and 2016 that narrate distinct moments in the slow unraveling of the global revolutionary left, with reference to Germany, the Netherlands, Japan, the United States, Palestine, and Lebanon, but always centered on Bangladesh. (United Red Army was first installment in the series.) “The turbulent 1970s were a text-book case of third-world disillusionment,” Mohaiemen wrote in an essay in the Sarai Reader, and his films explore several varieties of disillusioned experience. He speaks often of the need for a “global history” that does not simply replace Western historical narratives with those of the “Global South.” Mohaiemen stands for history as an uninterrupted, living narrative, in which individual stories can only be fully understood in relation to one another.

In Afsan’s Long Day (2014), another chapter of The Young Man Was, the central protagonist is Afsan Chowdhury, a trilingual activist and intellectual whose family migrated from West Bengal to Bangladesh. He is an unusual choice: neither a party member nor a “major player” in the leftist movement, today Chowdhury is a development consultant working with human rights NGOs. In 1971, however, he was a high school student in Dhaka. “To me, Afsan Chowdhury is interesting,” Mohaiemen says. “He wrote a diary entry in English about almost getting killed in 1973, and a novel in Bengali about the war and its aftermath, called The Betrayers.” Mohaiemen treats him with great empathy. In the film, Chowdhury sits at ease in the center of the frame, wearing a thin white shirt, the camera cut close to his face. He is a proud man, making a point of informing us that he has read Marx in English, and emphasizing his family’s distinction as migrants from West Bengal. Chowdhury’s “betrayers” are not those who sided with Pakistan in 1971 but those who led the country in later years.

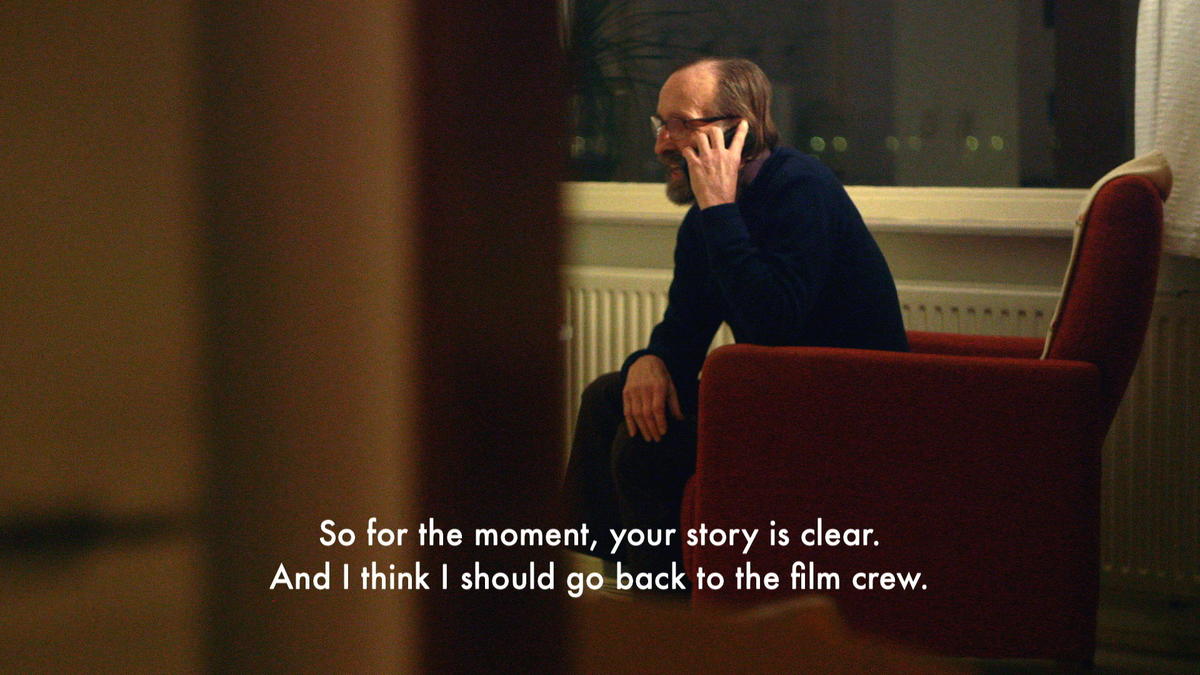

Mohaiemen is adept at finding unusual and compelling protagonists. Alongside his art practice, he is pursuing a PhD. in anthropology at Columbia University, where his dissertation focuses on Bangladeshi communists from the liberation struggle who are now historians of that period. In his research he discovered that many Europeans, inspired by Che Guevara’s moves in Africa and South America and excited by the prospect of a leftist moment in Bangladesh, had come to the new nation to volunteer as doctors, journalists, and lawyers. Peter Custers was one such individual. In Last Man in Dhaka Central, which premiered at the Venice Biennale in 2015, Mohaiemen conducts an extended interview with Custers, a Dutch man who abandoned his graduate studies at Johns Hopkins University in the US. “He comes into Bangladesh imagining himself a part of it all and gets swept up in things,” Mohaiemen tells me. “He gets arrested, tortured, expelled — and then, for the rest of his life, he is waiting to tell that story.” Custers first approached Mohaiemen at a film screening, speaking in Bengali, and they exchanged numbers. “I don’t know that I was the right person to tell that story to — I was just the person that showed up.”

Mohaiemen’s work may seem melancholic; it dwells with bleak histories and often hinges on moments of dashed hopes and lost opportunity. But as his relationships with people — and even with the archive itself — suggest, his approach is one of tenderness, and he is not immune to optimism. He is generous with his time, and critically attentive to his own privilege. I began an email correspondence with Mohaiemen a few years ago, shortly after I moved back to India from the UK. I was interested to know how he negotiated the dissonances of arts infrastructure in the subcontinent, where everything always comes down to caste, class, and who has access to what discourse. I was consolidating my own cynical readings of the South Asian art scene, reading Eve Kosofsky Sedgwick on “paranoid reading and reparative reading” and trying to be less paranoid. “You mention ‘reparative readings of the art scene,’ and I think this is of less interest to me just now,” Mohaiemen wrote to me at the time. “Because I am bilingual, I have a more-than-I-should-have space in the discourse, and that’s not healthy for me. There is no dream time in such a situation.” I wonder about this “dream time” now, particularly in the wake of his Turner Prize nomination.

Near the end of our long conversation, I share with Mohaiemen my concerns about the system of visibility governing access to the international art world — how artists are expected to speak to and for certain politics, synthesizing (or flattening) complex histories. Politicized work can be so fraught, so many of its gestures, empty. “But who’s to say that my gestures are not empty, too?” he says with a playful smile. “All the conversations about where the work is being shown, who is buying it, what the artist stands for — they’re still part of the art world’s circular conversations. We forget to look at, to talk about, the work. Let’s get back to that.”