From high in the California sky, a camera swoops over Los Angeles’s Westside, makes a treetop-level sweep of a tony street, and proceeds to a full-frontal view of a generic rich-person mansion, finally settling on a spacious bathroom interior. A bald white man is singing a merry tune from behind a foggy shower door. One beat we’re nodding along to a Mary Poppins song, reassured that life is sweet, the job’s a game, that ev’ry task we undertake might yet become a piece of cake. The next we’re crammed inside the stall, the man’s rangy, wet, seventy-year-old torso partly obscured by steam as he seethes at a soap bottle’s uncooperative pump, his whole being pledged against these few bits of plastic, a small metal spring.

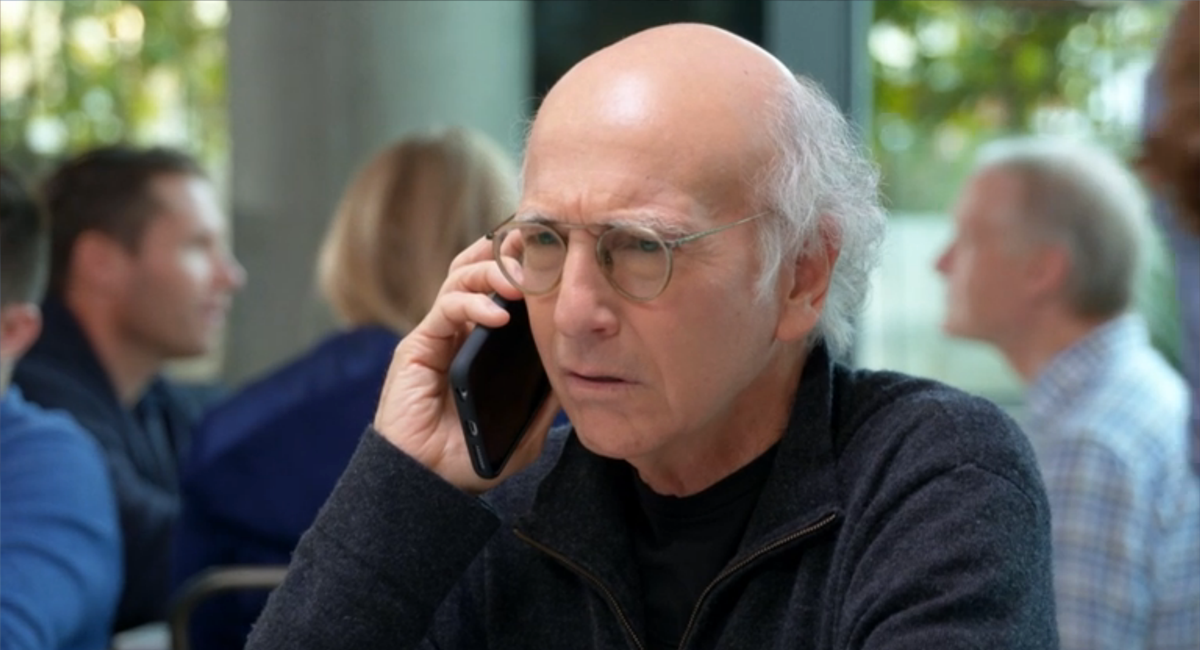

The man is Larry David, auteur comedian, in the opening moments of the latest season of HBO’s Curb Your Enthusiasm. The segment raises one of the show’s oldest questions — is Larry enraged by the thing in his hands or by the hands themselves? The eruption of barely-motivated slapstick hostility has been one of Curb’s go-to moves, as evidenced by any number of memorable skirmishes over the show’s nine seasons:

Larry ignores instructions not to use a bathroom where a dog is being kenneled, is bitten on the penis.

Larry comes to blows with the Joseph in a Living Nativity scene after making suggestive remarks about the Mary.

Larry flips open an umbrella, tearing the veil off a shy Muslim girl’s face.

Larry fights a rapidly escalating battle against various forms of packaging.

The entertainment factories may roil with the discovery of epidemics of workplace harassment, assaultive masturbation, rape. Donald Trump may sit in the White House, changing the country’s channels. And yet Larry’s speedy unraveling when faced with the soap-pump seemed to suggest that not too much had changed in Curb’s universe, the war of all against all against nothing proceeding apace.

Signs of Curb’s return from its six-year hiatus had begun to appear in the summer of 2017, the promos thrumming with low-frequency menace. “The world needs him now more than ever,” the billboards read, Larry David’s face projected onto a cloudy sky like the Bat-Signal. Another advert showed him in Roman drag, a bespectacled Caesar having crossed some Rubicon. We are living, no doubt, through a dire and complex moment, but HBO’s campaign was vague as to precisely which exigent circumstance was summoning David out of retirement.

Soon after the season arrived in October, however, it seemed clear enough. The first few episodes were effectively lightning rounds of “Things It May Be Politically Incorrect To Joke About.” A list of people, really. Muslims, gays and their weddings, and the disabled all made the list, as did black girls living under threat of female genital mutilation and white transgender people. (“Keep up the good work,” says series regular Marty Funkhouser (Bob Einstein), by way of introducing his ex-daughter, now son.)

Season 9, it turns out, is Curb’s woke season — or rather, its anti-woke season.

Although the show’s white-on-white assaults (Jewish-on-Jewish, as often as not) have tended to outnumber all others, David has of course been fighting a low-intensity war with the etiquettes and protocols that structure polite society for decades. Indeed, most of these folks have been targeted before to better effect, in story arcs more akin to conspiracies than to plots. The straight description of a given episode barely hints at the scope of its yucks and affronts, as with HBO’s encapsulation of Season 2’s “Trick or Treat”:

Larry offends a Jewish neighbor at the premiere of another friend’s movie. Later, Larry experiences the ‘trick’ side of the Halloween expression ‘trick or treat’ when he questions the age of two girls who want candy.

That the incidents will be linked; that the alleged offense will be Larry’s whistling Wagner’s “Seigfried Idyll” past the graves of six million Jews; that the moviemaking friend, Cliff Cobb, is in a wheelchair, and that Larry’s attempt to appear sympathetic to his disability will produce its opposite; that Larry will offend Cliff by yawning during the premiere and offend Cliff’s wife by declining to sleep with her; that the uncostumed trick-or-treaters are indeed too old to be begging for candy; that Larry will tell the police that he has been the victim of a hate crime against bald assholes; that Cliff will assert a spurious biographical link to the inventor of the Cobb Salad; that Larry will give his wife Cheryl a gently beautiful birthday gift of music; that he will ruin this gift, only to find a gloriously mean-spirited profit in it; that Larry’s glorious profit will itself prove to be the episode’s only hate crime, in the form of a rousing live performance of the overture from Wagner’s Die Meistersinger von Nürnberg on his Jewish neighbor’s lawn, conducted by Larry himself — that all of that can fit within the show’s synopsis and also completely exceed it is Curb’s peculiar genius.

David performs a similarly audacious trick on his own character, creating a funhouse version of himself — let’s call him Larry — that magnifies any quality that might be considered obdurate, difficult, or absurd, and somehow recasts him as an everyman (or anti-everyman), the bulk of his interactions a sort of echolocation by chutzpah. It’s a remarkable achievement on multiple levels, not the least of which being his relative anonymity before he materialized fully-formed on HBO in 1999, a man in his early fifties, his co-creation of Seinfeld reconfigured as a semi-secret origin story. David’s brazen self-reinvention effectively introduced a new character to that show retroactively: hovering over Jerry and his neighbors Elaine, George, and Kramer, we can now make out Jerry’s fellow comic and collaborator, Larry.

Curb Your Enthusiasm is widely admired by critics and audiences for its volatile yet remarkably stable amalgam of mockumentary, reality television, and situation comedy. Our ongoing sympathy for Larry and David for nigh on two decades testifies to Curb’s mastery of its formulas, the improvisatory genius of its cast, the acumen of its editors.

Like Seinfeld, the show from which it spews like bounty from a cornucopia, Curb is full of minutely-crafted doppelgangers and weird doubles. Having cloned David and force-multiplied the absurdist zig-zagging at the core of his standup, Curb rearranges select parts of David’s Los Angeles milieu into a maze for its lab rats to run. The carefully-maintained cleanroom’s outer membranes are semi-permeable — the more famous the guest star, the more likely they are to play themselves — but once inside, the gap between personas grows. Perhaps the finest (and most terrifying) of these simulacra is Curb’s version of Michael J. Fox, Larry’s upstairs neighbor in Season 8. Against a typical barrage of Larryian provocations, the actor and activist weaponizes his Parkinson’s disease, casting shade, clomping around in heavy boots above Larry’s bedroom late at night, proffering an explosively well-shaken bottle of Coke, always with plausible deniability. (“It’s all Parkinson’s, Larry,” Mike says, not unsmiling.)

In its way, Curb’s obsession with doubling and duplicity targets the insular world of Lalaland, its limousine (or Prius) liberals and their various causes, and — foundationally — its Jews. David’s ongoing assault on his coreligionists is one of Curb’s core fixations, as is the general frame of group identity. Even as Larry’s world remains vividly, resolutely Jewish, he is constantly running up against the boundaries of that world’s local proprieties as they relate to various shades of people of color, the gays, and the differently abled.

Larry’s relationship to African America is a particularly rich seam. In Season 6, Cheryl’s penchant for checkbook crusading ultimately results in a family of displaced hurricane survivors — the proverbial Blacks — moving in with them temporarily. Before the season is over, Larry will hook up with the Black family matriarch Loretta, played with real relish by Viveca A. Fox. But despite the pretense that Loretta might be Larry’s perfect woman, Curb denies its audience a peek at their liaison, preferring to insinuate Loretta and Larry’s sex the way a crumb-strewn plate insinuates a sandwich: in bed, the morning after, both of them somehow fully clothed. It’s at best a hieroglyphic insert.

Riding high over all of these Blacks is Loretta’s cousin Leon, played by comedian J. B. Smoove, who moves in and never vacates — Cato to Larry’s Inspector Clouseau, Kato Kaelin to his O.J. If Curb has a single clearly-identifiable relationship ideal, it is Leon and Larry, bald ebony and bald ivory. Like almost everyone in Larry’s inner circle, Leon is a dependent, but the penny-ante scope of their financial entanglements means he can take or leave Larry in ways that, say, his manager and factotum Jeff (Jeff Garlin), with his mortgages, cannot. Although he sits several rungs down the totem pole, relentlessly hype-manning from the guest house, Leon — like one of Norman Mailer’s (black) Negroes — embodies a complete freedom to which Larry, with his near-billions, can only aspire.

Crucially, Leon is impossible to offend, being cut from the same cloth as Larry. There is no excess on which Leon will not double down, no unmentionable he will not mention. Leon performs a necessary office for his patron: he normalizes Larry, transforming his stray less-than-salutary thoughts into conventional wisdom through the force of his amplifications.

Consider Leon’s Goatse-like riff from Season 6, a response to Larry’s embarrassed confession that he has allowed a skinhead to verbally abuse him:

“Listen to this, alright?” says Larry. “In the doctor’s office earlier, there is a guy sitting there — a skinhead, okay? He looks at me and he says: ‘What the fuck are you looking at, jewboy? Fucking faggot.’”

Leon leans into Larry’s face and, correctly diagnosing the root of Larry’s disquiet, skips over the anti-Semitic slur to go directly to the homophobic one. He then rehearses for Larry a phantasmagoria of a new, indomitable self, holy and giddily unhinged:

Leon: Next time a man calls you a fucking faggot, you get in that ass, Larry. Know what I mean? You get in that ass, Larry. That’s what the fuck you do.

Larry: What are you talking about?

Leon: You let that man slide today. You gotta immediately get in somebody’s ass when that happens to you. You pull their asshole open, step into their asshole, close the door behind you. Take a spray-paint can, right?

Larry: Uh-huh.

Leon: “Larry was here.” You spray paint “Larry was here,” “wash me,” all that kind of shit. Fuck his whole asshole up. Eat some Snickers bar, throw some paper on the floor, read a newspaper, ball the paper up… throw the newspaper on the floor. Fuck his whole asshole up, you know what I’m saying? Then you open that asshole one more time. Open it again! Open that asshole again!

[Larry, using two hands to pantomime the opening of a person-sized asshole]

Leon: Uhnnh! Step out of his ass [stomps foot] and leave that motherfucker wide open so he knows you’ve been there.

Larry: Open it up, step in…

Leon: Step in their asshole —

Larry: Spray-paint “Larry was here.”

Leon: “Larry was here.”

Larry: Leave garbage… Snickers, eat Snickers. Leave garbage…

Leon: Spit! Fuck it.

Larry: Get out!

Leon: Mmmm!

Larry: Get out, open it up again.

Leon: Step out their asshole —

Larry: Step out…

Leon: Don’t even close that motherfucker. Leave it open so he knows you’ve been there. You feel me?

Larry: I got you.

Leon: That’s how you handle people.

Leon looks down on him with genuine tenderness. Larry walks out spent, energized, and grateful all at once.

“Get In That Ass” is a masterpiece of frustrated desire and detourned animosity. Beautiful and awful at once, its undisciplined energies collect and bloom in safety by virtue of having been directed by both men toward unnamed and absent third parties — toward the that-ass at the heart of the world.

Curb’s previous season, back in 2011, saw Larry fitfully settling into post-divorce life, charting the vicissitudes of reverting to singledom in one’s sixties. The final episode introduced Greg, the son of one of Larry’s fleeting love interests. A six-year-old obsessed with Project Runway, Greg the Flamboyant Kid takes a special interest in one of Larry’s Hitler doodles:

Greg: Ooh! What’s that right there?

Larry: Oh, that’s called a, uh, swastika.

Greg: I like how the lines just go straight… and then up and then down and then straight and then up and then down. It’s beautiful! My birthday’s coming up in a week, so — can you get me one?

Larry: A swastika?

Greg: Yeah!

Larry: I dunno, Greg, I’ll have to think about that.

Greg: They should start selling them in every gift shop in New York City.

Larry: Yeah, I don’t think Jews would like that.

Greg: Get a life, Jews!

Larry gives Greg a sewing machine for his birthday, instead. Had Season 8 turned out to be Curb’s last, it would have been a perfectly fine end to things, a satisfying coda to a television-altering run.

Season 9 finds Curb in a rush to ruffle its audiences’ pieties. A show that would spend whole episodes, sometimes whole seasons, working through its provocations now seems content to namecheck them. This robs Curb of certain alchemical possibilities; some of the show’s best jokes have been those that go unuttered. Riffs that might have looped around several times, compounding their payoffs, now arrive fully articulated as annoyances and demands for conformity.

This brisk, lean pace is apparent in an early spat with Richard Lewis, who plays himself in the role of Larry’s oldest friend (and hence oldest living human subject):

Richard: My bird died, and you sent the most ridiculous, despicable text…

Larry: You know, it’s a dead parakeet. That’s a funny thing…

Richard: There’s a lack of empathy and compassion and sympathy for practically everything in your life.

Larry: There is — there’s a lack of everything. Look, you’re a comedian. You’re supposed to be able to take a joke, you know. You’re supposed to laugh about everything.

Richard: Just because I’m a comedian, I have to find everything in the world funny?

Larry: Yes! Yes. Yes. Everything’s funny.

This is not the first (or hundredth) instance of Larry lamenting someone’s inability to take a joke — or of someone taking issue with Larry’s sense of humor. But it is a stilted exchange, somehow both bloodless and overblown.

Larry’s insistence that everything be fit to joke about echoes similar notions expressed in recent years by Jerry Seinfeld, his former co-demiurge, who has been keeping himself busy with the aptly titled show, Comedians in Cars Getting Coffee. Seinfeld has taken to decrying “this creepy PC thing that’s out there” and its harrowing effect on American comedy. “They just want to use these words,” he told ESPN radio host Colin Cowherd. “‘That’s racist. That’s sexist. That’s prejudiced.’ They don’t even know what they’re talking about. I have no interest in gender or race or anything like that. But everyone else is kind of, with their calculating — is this the exact right mix? I think that’s — to me, it’s anti-comedy. It’s more about PC nonsense.”

Larry David, of course, is very interested in gender and race and anything like that. Despite their long friendship and lucrative working arrangements, David’s shtick — belligerent and incisive and self-defeating all at once — has always been distinct from that of Seinfeld, with his blithe dismissiveness and imperturbable self-regard. Both men trade in forms of high-end obliviousness, but David’s craft has been defined by compulsive self-examination, a habit of mind that places his lodestar more in Woody Allen’s anxious constellation.

2017 too often finds Curb in a defensive, Seinfeldian crouch. In one of the season’s first gambits, Larry gets called out for failing to hold the door open for a butch woman named Betty (Julie Goldman). “I didn’t really get an ‘after you’ vibe,” Larry explains. As their interaction devolves, Larry winds up giving what might be the Platonic form of the misunderstood nice guy’s non-apology: “I was just trying not to offend you and yet I wound up offending you. Which is quite ironic…” Larry proceeds to play a role in scuttling Betty’s marriage to femme Numa, played by Iranian-American SNL alum Nasim Pedrad, on the grounds that their planned roles in the proceedings (Betty as bride to Numa’s groom) are inverted.

“You’re not groomey, she’s not bridey,” he tells Numa.

“What kind of psychopath interferes with the nuances of a lesbian wedding?” Numa demands. While Numa’s cause is righteous, the line is more than a little on the nose, as though a guideline about lesbians from Curb’s show bible (“Larry is the kind of psychopath who interferes with the nuances of a lesbian wedding”) somehow found its way into the script.

Contrast these bland contretemps with a signature moment from Curb’s very first season, in which Richard and Larry are squabbling down by the water in what appears to be Santa Monica. Their argument is interrupted when Richard recognizes a friendly face jogging by and stops to introduce Larry to the man, who is black.

Richard: Doctor Grambs, this is my friend, Larry David. [To Larry] This is my dermatologist.

Larry: Really?

Grambs: What, for fifteen years already?

Larry: Even with the whole affirmative action thing?

Grambs: I’m sorry. I beg your pardon, what?

Richard: What do you mean?

Larry: It was a joke.

Grambs: What do you mean, “The whole affirmative action thing?”

Larry: It was a joke.

Richard: He’s like a buddy.

Larry: No, no, no.

Richard: I know him, he’s a sweetheart.

Grambs: The implication being that I wasn’t good enough to be a dermatologist?

Larry: No, come on, it was a joke.

Richard: He’s a liberal — he’s like you and me.

Grambs: So, if I wasn’t black, he would have said the same thing or not? Do you see my point?

Richard: I see it in a historical sense, but not in a nice-day sense.

Grambs: You know, Richard, I’ve worked too hard and too long at this. I can’t do it. I don’t know what his trip is, but I can’t do it.

[Grambs turns to leave]

Larry: [calling after him] I don’t have any trip! No, it was joke!

Larry, in a daze, repeats the phrase, “I was just trying to be affable” before suddenly interjecting, to himself as much as anyone: “I tend to say stupid things to black people sometimes.” David nails the scene, Larry’s confusion, self-awareness, and sense of alarm all vying for attention. The scene is both genuinely cringe-inducing and disarmingly funny. Larry’s defects here are questions of character with political implications, rather than the other way round. He is a loose cannon aimed in every direction, including at himself.

All of which is to say that that perhaps Seinfeld has a point. Curb’s decision to sign up for the rearguard action against political correctness has had a numbing effect on its sense of humor; its comeback season is, by most accounts, its least funny on record. In making so strident a case in defense of pure humor, Curb now seems too willing to let itself off the hook. But that wriggling, ethical and otherwise, has always been a big part of its appeal.

About twenty-five minutes into Season 9, a fatwa is issued by Iran’s Supreme Leader calling for Larry’s death. The offense: an appearance on the Jimmy Kimmel show to promote a Broadway comedy about Salman Rushdie — Fatwa! The Musical — which Larry has apparently been working on for years. Larry watches his television with mounting, dumbfounded alarm as a (fictional) ayatollah denounces him in Farsi. Larry promises to do anything, face any (reasonable, low-grade) punishment, repent, convert to Islam, whatever, even as his newfound Iranian nemesis explicitly anticipates each such effort as too little, too late to save body and soul.

While putting Larry under a death sentence might seem like a promising ratcheting-up of dramatic stakes, a fatwa feels like an oddly dated storyline at this moment in time, a guest star from another era. Indeed, true to David’s yen for eternal (comedic) returns, this is neither Rushdie’s nor his fatwa’s first appearance in Greater Larryland. In “The Implant,” a 1993 episode of Seinfeld, a curious, perhaps spurious analogy is drawn one afternoon at the gym. Kramer believes he has spotted Salman Rushdie chatting up a woman named Sidra who Jerry has been dating. The writer may be going under the name Sal Bass; in fine Davidian-Seinfeldian form, whether Sal is Salman becomes joined to whether Sidra’s tits are real or fake.

Elaine brushes off the details of l’affaire Rushdie with a quip: “you got five million Moslems after you, you wanna stay in pretty good shape.” Curb does not linger on the details of the doom hanging over Larry, either. The ruling has no discernible underpinnings, theological or otherwise, beyond the ayatollah’s failure to appreciate Larry’s unskillful impression of him. (And who would, really? David is a brilliant comedian but a mediocre impressionist, born to play just two characters, Larry David and Bernie Sanders.)

The lack of specific texture allows the edict to stand in for something more fundamental to Curb, the exercise of judgment itself. John of Damascus considered judgment “greater than any other virtue, the queen and crown of all the virtues,” and Larry would agree. His inability to leave well enough alone on any subject ever is best understood as a quest for near-scientific levels of discernment. This compulsion undergirds his daily sense of injury and demands for satisfaction, his tendency to blurt unsolicited, producer-like notes at every and anyone around him. (It should be noted that, like the worst Hollywood producers, Larry’s judgments tend to fall most heavily on underlings: waiters, waitresses, and administrative assistants, as well as an array of service workers.) Larry’s increasingly elaborate escapades over the years have been a search for higher power in this regard, the fatwa story serving almost as a culminating event. When a skeptical Jeff wonders aloud who Larry imagines in his play’s starring roles, Larry admits that he’s thinking of playing the ayatollah himself.

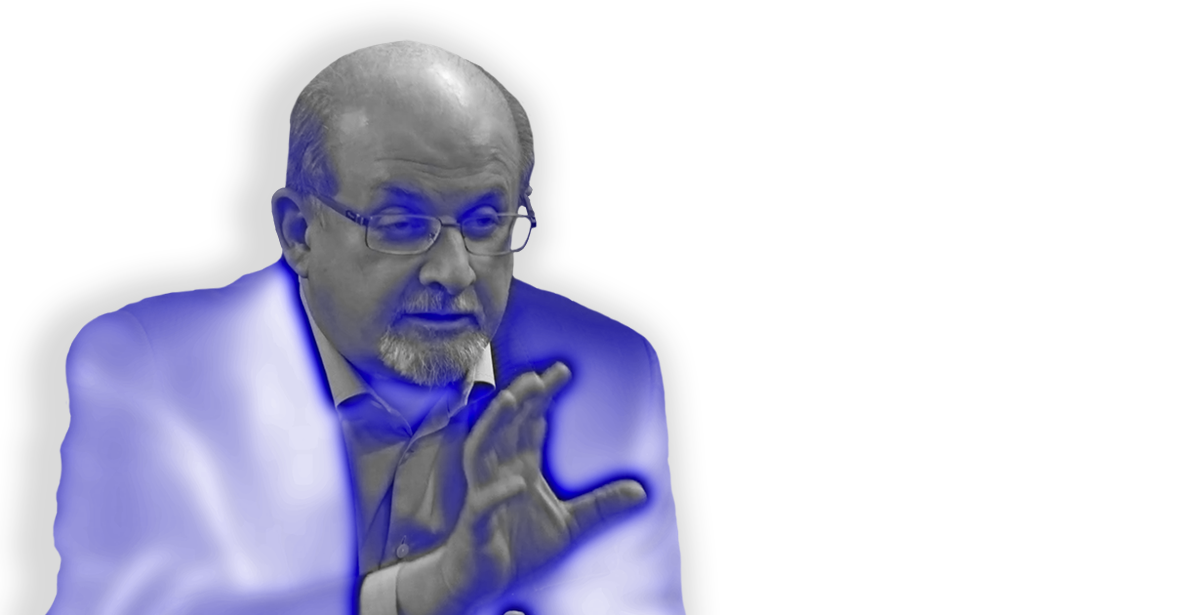

Of course, the fatwa on the author of Fatwa! casts Larry in the Rushdie role — not a bad alternative, given that spirited self-justification comes as naturally to Larry as spirited prosecution. A scene in which Larry submits the shape and texture of his life under fatwa to the judgment of Salman Rushdie, playing himself, ought to have been one of the season’s apogees. The great man holds court in a butlered Los Angeles mansion and renders a snap thumbs-down on the whole of Larry’s post-fatwa existence, beginning with his disguise, a grey-wigged and mustachioed getup that marries the Unabomber and Travis Bickle.

Larry’s meeting with Rushdie results in something akin to a generic talk show field interview. He sits across his fellow septuagenarian, interviewing him from a posture that can only be described as deferential, Curb’s native comedic imperatives attenuated to public-service journalism.

Rushdie tells Larry that fatwas and their issuers must be vigorously resisted. He also tells him to ditch the disguise, venture out into the world and live his life naked and unafraid. Literally. “There are things that you gain,” explains the knighted winner of the Man Booker Prize for Fiction:

Salman: You are a dangerous man. There are very beautiful women who like that.

Larry: Really?

Salman: Yeah.

Larry: Even with me they would like it?

Salman: It’s not exactly you; it’s the fatwa wrapped around you. Like a kind of sexy pixie dust.

Larry: Huh.

Salman: Be a man. Stop this, and fatwa sex will follow.

Larry: Fatwa sex?

Salman: The best sex there is.

Mind you, “the best sex there is” is no small boon, considering Larry’s difficulties getting properly laid — whether married, single, on wife-approved commitment leave, or divorced. But having Rushdie on hand to deliver this good news does neither Curb nor the author much credit. Rushdie’s blank expression breaks every shot it appears in, while his words — presumably largely improvised, like the bulk of the show’s dialogue — only serve to underline certain judgments that have attended him, mostly to do with smugness and vanity, skirt-chasing, the enthusiastic pursuit of a glitzy non-literary celebrity that felt dated even when it was new.

Padma Lakshmi, Rushdie’s wife for four years in the 2000s, discussed her experience of fatwa sex in her 2016 memoir, Love, Loss, and What We Ate. A contemporaneous New York Daily News item provides an unstinting portrait:

Lakshmi was suffering increasing menstrual pains, which were actually an undiagnosed condition called endometriosis, in which womb tissue grows outside the uterus. The agony was so severe it could leave her hunched up in bed for days. It also made sex incredibly painful, but the ever-libidinous Rushdie simply assumed she was inventing an excuse for their lack of intimacy.

Denied sex on the night of their second wedding anniversary because she said she was in such pain, he acidly commented: ‘How convenient for you … what is it this time?’ Later that night, she had to be rushed to hospital, but even then Rushdie fretted only about his own unsatisfied sexual needs, she says.

On closer inspection, most of Rushdie’s instructions on how to turn a fatwa-frown upside down — his only real comedic function — merely recapitulate Larry’s longstanding practice. There is no disadvantage that Larry will not attempt to put to dialectical use, particularly in the swamps of his own making. A few episodes after this encounter with Rushdie, Larry will successfully reset a strained relationship (he has alienated a friendly African American auto mechanic by blurting out that he doesn’t “sound black”) by pretending to have Asperger syndrome. Larry can and will make lemonade out of anything, up to and including imaginary lemons.

Rushdie’s superfluous presence tells us more about David than Larry, the “get” testifying to his and HBO’s off-screen powers. Rushdie’s superfluous advice, meanwhile, seems uncomfortably close to “locker-room talk,” just a few degrees to the side of the assurance that “when you’re a star, they let you do it. You can do anything.”

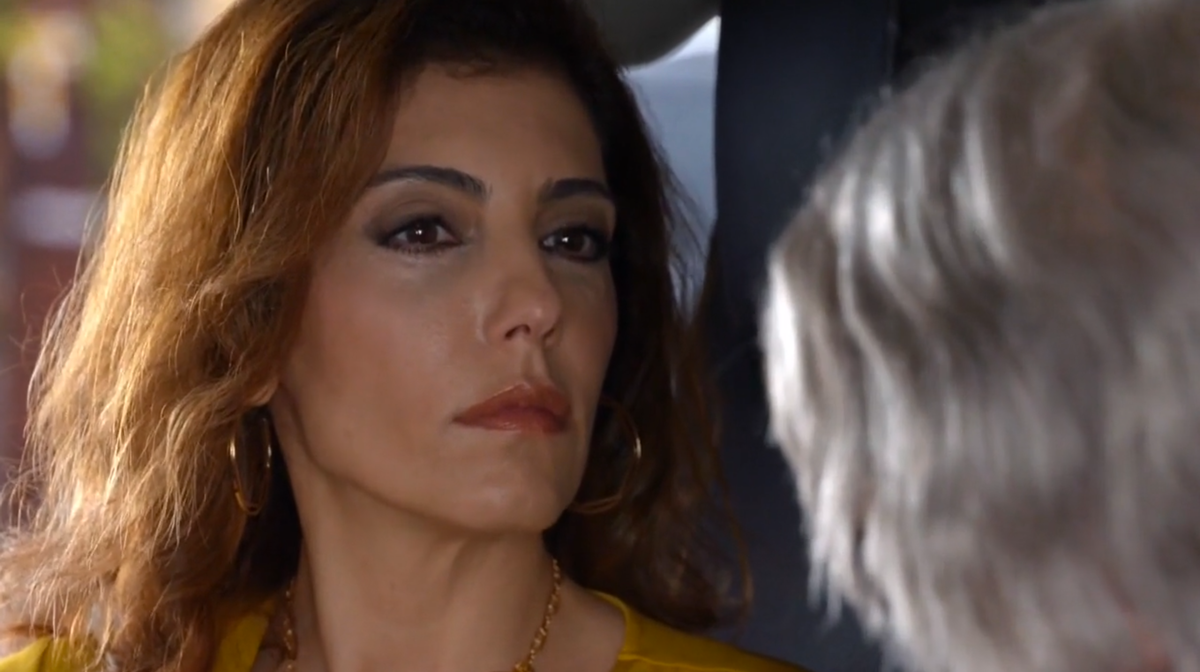

The promise of the pixie dust proves similarly illusory. Larry is too Larry to take sexual advantage of his fatwa glamour; his one confirmed bout of fatwa sex will be with a repeat assignation — a Muslim, no less. For Larry, the best sex there is was the sex he had with a Palestinian woman named Shara, during Season 8’s milestone episode, “Palestinian Chicken.” Like many of Curb’s experiments, their encounter proceeds from social fact — the gap between Palestinian and Jew in America — to articulate an internally plausible and reasonably comedic non-resolution. Played by Canadian-Armenian actress Anne Bedian (née Nahabedian), Shara gives as good or better than she gets. Their dialogue — her monologue, really, with Larry’s annotations — during the deed is redolent of “Get In That Ass.”

Shara: Fuck me, you fucking Jew!

Larry: “Filthy Jew.” Filthy Jew!

Shara: Filthy fucking Jew! You Zionist pig. You occupying fuck. Occupy this!

Larry: Yeah, yeah, I’m an occupier. I’m an occupier.

Shara: I’m going to fuck the Jew out of you.

Larry: Yeah, well, that’s not so easy.

Shara: You want to fuck me like Israel fucked my country? Show me what you’ve got!

Larry: This reminds me of something Theodor Herzl once said…

Shara: Take it, Jew. Take it, Jew. Oh! Fuck me, you Jew bastard! Fuck me like Israel fucks my people! Show me the promised land, huh? Labe, son of Nat.

Larry: Keep my father out of it, will you?

Shara: You circumcised fuck!

Larry’s first response to the fatwa is to go see Shara. He tells her that he has no choice but to come to her, that he has nowhere else to turn: “I don’t know any Muslims. They’re not in show business. They don’t hang out at the deli. Am I supposed to go into a mosque and then start chatting them up? Sure, maybe I can make a little more effort to seek them out, but they’re not really coming up to me either!”

These hyperventilations are more breathless than usual, Larry stumbling over pronouns, local demography, and the basic facts (such as they are) of Curb itself. The Los Angeles where David’s show is shot and set has the third-largest population of Muslims in the United States. Southern California in general is home to more people of Iranian descent than any place outside of Iran, their enclaves so much a part of the region’s mise en scène that they’re collectively known as Tehrangeles among even non-Iranians. Los Angeles is also said to be home to more Iranian Jews than anywhere in the world, many of them concentrated in Larry’s Westside stomping grounds. But all this is somehow beyond the show’s ken.

Curiously, it seems not to occur to Larry to reach out to Omar Jones, the Muslim private investigator Larry hired in Season 5 to find out whether he was adopted (this, in an effort to avoid donating a kidney to his friend Richard). Jones, carefully underplayed by Mekhi Phifer, first appeared in an episode titled “The Bowtie,” looking like a member of the Nation of Islam or perhaps a conservative political commentator. An African American Muslim, Jones is initially skeptical of Larry. Jones has lines he does not want crossed, and he is miraculously able to convey these to Larry and insist on their observance without blowing up their working relationship. He patiently listens to Larry from behind steepled manicured fingers, surrounded by Afrocentric paintings, African sculptures, and framed photos of his beautiful, safe, and healthy black children. (Jones has the air of someone who understands very clearly what money can buy.) Jones leaves Larry at the end of that season well-paid and open to working with him again, but Omar Jones will not be called upon to help Larry now with the fatwa. He is diligent and as generally capable as anyone can be in Curb. But he is also black. No matter how orthodox his piety, he operates under a different sign.

As it happens, Larry’s salvation will come from another Muslim PI, the Cutting Man. Near the end of the season, Larry comes to the defense of a man who is being pilloried for cutting the line at a buffet. Played by Iranian-American actor Navid Negahban of Homeland, 24, and other better-than-the-material turns, this man turns out to be one of Larry’s would-be executioners. Their accidental encounter pitches the story in another direction. Moved by Larry’s outsized defense of obscure principle, he decides not to kill Larry, choosing to advocate for the lifting of the fatwa, instead.

Cutting Man does this by staging a Greatest Hits of Curb Your Enthusiasm under the pretext of investigation. Notebook in hand, he interviews such signature set-piece subjects as the Car Pool Prostitute, the Not-Dead Kamikaze Pilot, and Wendy Wheelchair (or was it Denise Handicap?). He talks to Big Vagina Lady and Krazee Eye Killer. He politely declines a Coke from Michael J. Fox. He relitigates the past, really, extracting testaments to Larry’s good character from each interviewee.

The sequence is a live-action rendition of a staple of Curb fan blogging, the listicle detailing “X Times Larry David Was Right.” It is also a recapitulation of a far stronger sequence in Season 5, in which Larry, on his seeming deathbed, is asked by a rabbi if he has anything to atone for. Larry looks off into that middle distance where all flashbacks take place and bears witness to a nearly three-minute crescendo of shouting, scuffles, accusations, hurled expletives, and anguished cries of LARRY!? “Nah,” says Larry. He’s good, thanks. It is one of Curb’s finest sequences, at once appalling and comforting. It seeks to prove nothing beyond Larry’s willingness to die with his boots on, fully committed to the life he’s lived.

By contrast, Cutting Man builds a case for Larry’s virtue through sometimes hostile cross-examination, his questions designed to carry weight with the imaginary theocrats from the Islamic Republic. Evidence is tendered that Larry is no Islamophobe; that he is not a pervert, not actually racist, nor sexist; that he harbors no ill-will toward the disabled or the chronically ill. The Cutting Man never attempts to disprove that Larry is a self-hating Jew. On the contrary — he interviews_ an orthodox Jewish woman whose devotion leads her to leap from a ski lift in mid-air rather than be caught next to Larry after he scoffs at her request that he jump himself.

“So he refused to follow the tenets of Jewish orthodoxy,” the Cutting Man summarizes, as if maintaining gender segregation on a ski lift after dark were a tenet of Jewish Orthodoxy anywhere outside of Larryland.

“Oh, absolutely,” says the Orthodox woman. “Big time.”

The jumping woman sits close to both David’s pet interests and Larry’s pet peeves. The overall strangeness of Los Angeles’s under-assimilated or culturally resistant Jews is a recurring theme. The peculiarities and hilarities of Jews who are not Larry, Jeff, or Richard, their fealty to obscure forms of specificity, constitutes a category of otherness unto itself in Curb that is anterior to all other Others, from African Americans to Muslims to lesbians to women. Family and seders, charity events and funerals — many, many funerals — form a charged grid of affinity into which Larry (and, for seven seasons, his non-Jewish wife) is fully plugged even as he renounces its more atavistic currents.

It is, for example, impossible to imagine either Larry or David attending, as Jerry Seinfeld and his family recently did, what Haaretz described as an “anti-terror fantasy camp” — the Caliber 3 Counter Terror and Security Academy, a live-action theme park in the West Bank that featured “a simulation of a suicide bombing in a Jerusalem marketplace, immediately followed by a stabbing attack, a live demonstration with attack dogs, and a sniper tournament.” Whereas it is not at all difficult to imagine David joking, as he in fact did during a Saturday Night Live appearance late last year, about the difficulties he might have encountered trying to pick up women at a concentration camp.

This all likely cuts closer to the bone for David than he allows it to cut for Larry. Appearing on Finding Your Roots, Henry Louis Gates, Jr.’s chromosomal update of This Is Your Life, David shares that his family refused to discuss their respective heritages with him. His own sense of self, as he describes it at least, begins with his childhood in Jewish Sheepshead Bay, Brooklyn, and does not extend past the deliberately vague recollections of a few aunts and grandparents.

Gates uses Larry’s DNA and a team of researchers to fill the gaps. In a crisp, salesman-like litany, he informs David that Rose, the name he has known as his mother’s his entire life, was not her birth name; that the entirety of her Polish family was wiped out in the Second World War; that his father’s family was mostly German; that another portion of his father’s family had roots in Alabama’s antebellum Jewish enclave; that they owned five slaves. This torrent of new information leaves David visibly subdued, and in that quiet we get a more definite sense of the gap between him and Larry. David is smarter than Larry, more self-assured, slower to quip as he works out an idea. We can see more than one wheel turning behind his eyes, where Larry has just one gigantic wheel, which spins faster or slower as needed, and is prone to wobble.

David is shocked by Gates’s news, but maintains enough comedic sangfroid to apologize for the whole owning slaves thing. It seems like something Larry would say. This exchange sets certain things about the show in high relief, revealing that the uneven, slippery ground where ostensible character and actor meet is the fault line on which Curb has been built. Our shifting feelings about the biographical fallacy is the very mechanism that creates the show’s funhouse effects. The man who claims not have much by way of deep identity has created a show almost entirely about identity.

The Cutting Man presents the case for the defense to a council of lunching mufti, who come to see in Larry a kindred spirit. And why shouldn’t they? Like Larry, the empaneled are aging judges, their performances pitched in the rough vicinity of the Moses scene from Mel Brooks’s The History of the World Part 1. They all find the present confusing and annoying in equal measure; everyone hates it when someone hogs the ketchup. “What choice did he have?” one of them exclaims after the Cutting Man makes a particular case. Larry will be allowed to live, the fatwa lifted with two episodes to go.

Before leaving his tribunal, Larry asks the mufti whether he could perhaps mount his musical comedy Fatwa! after all? Indeed he can, so long as it stars Lin-Manuel Miranda, creator of Hamilton. The stipulation opens the door to a very fine casting “get,” ushering in a range of productive difficulties. First, there is the problem of Miranda, who plays Lin-Manuel as a blandly conniving operator who can’t help helping himself to full control over Fatwa! During their first meeting at his agent’s office, Lin-Manuel positions himself behind the desk, relegating Larry and Jeff to the role of supplicants. Lin-Manuel corrects Larry’s pronunciation of “Salman,” summarily rejects each of Larry’s suggestions as to casting and venue. He pauses the meeting to take a call, asks to be given the room.

“It’s the desk!” Larry fumes while they cool their heels. “He’s up high, I’m down low. Everything he says, I say yes to. He’s in the boss chair. It’s like he’s my boss!”

Like many such foils over the seasons and years, Lin-Manuel is kin to Larry, born under different stars. But where Larry’s demanding eccentricities almost invariably impel him toward self-defeat, Miranda plays Lin-Manuel with the self-possession and caffeinated drive of the victorious twerp, his pushiness reminiscent of the sort of nerd übermensch found on HBO sister sitcoms Silicon Valley and Veep. They could just as easily be working on an app as a play.

Then there is Hamilton. Larry is not usually cheap with his opinions, but he is uncharacteristically circumspect about Miranda’s illustrious creation. His feelings about the play are neatly sidestepped by the in-story fact that he has technically not seen it, having fallen asleep in the first act. Jeff, of course, thinks partnering with Lin-Manuel will be great, his assessment more art of the deal than theater arts. Larry has no real choice in the matter — the mufti have spoken, and like everyone else, they love Hamilton.

David, being a member of the One Percent in good standing, did not fall asleep on Hamilton in real life. “The real Larry David has seen Hamilton three times and hasn’t fallen asleep even once,” a Curb executive producer told The Hollywood Reporter, attesting that “I saw it with him for his second time, and I can say that he was one hundred percent engaged the entire time.” David himself is on the record calling it “pretty amazing.” The New York Daily News printed his capsule review: “No doubt about it, it’s an incredible show.” There was an asterisk, however, a slight reservation. “But I have a feeling there are a lot of white people who are saying they are completely blown away even though they didn’t really understand half of the things the people on stage were saying.”

On one hand, Hamilton is a walking, talking, rhyming apotheosis of the sorts of fraught crossroads encounters likely to draw Curb’s attention. Its admirers span all sorts of divides — “It’s the only thing Dick Cheney and I agree about,” Barack Obama enthused, via tweet. On the other hand, Hamilton’s success came at a mild but real cost to David. In the long hiatus before Seasons 9, David wrote and starred in a Broadway play titled Fish in the Dark. (David bequeathed his role to Jason Alexander, his actorly doppelganger of choice, for half of the play’s six-month run.) Fish in the Dark broke a Broadway record for spring-season presales and held it for two years… until Hamilton came along.

Diegetic or not, abstention from Hamilton fits Larry’s depicted temperament. (His specific concern over his inadvertent nap is framed as a typical “he said, Larry said” involving a professional oyster shucker who overhears Larry admitting his lapse and tries to extort him for Hamilton tickets.) Larry’s problem is analogous to his problem with Betty earlier in the season — he fears his new boss-partner Lin-Manuel will take offense despite his assurance that he did not intend to offend. Given that Larry is a habitual liar, his declaration that his yawn was not a review cannot be trusted. Given that Larry is also a compulsive oversharer, the absence of an opinion seems equally suspicious.

Offense and opinion — intentional and otherwise, spoken and unspoken — circulate like a preschool cold during these last episodes, dogging Larry in his dealings with Lin-Manuel and with the Fatwa! production more generally. By the end, judgment seems to be the characters’ only language in common. Larry is offended by how Lin-Manuel says thank you after he convinces Larry to put up some cousins visiting from out of town. Larry is annoyed that F. Murray Abraham, whom Lin-Manuel has cast as Fatwa!’s ayatollah, is paying too close attention to Larry’s daily fashion choices, while F. Murray does not appreciate that Larry has branded him as an outfit-tracker to the cast and crew. Larry is pre-offended at the notion that Bridget (a bawdy love interest played winningly by Lauren Graham) might spill the beans on his sexual prowess and tries to get her to sign a bedroom Non-Disclosure Agreement. (Leon’s idea.) Soon she is scoffing about “Larry Long Balls” behind his back.

Looming over all these proffered opinions is Larry’s non-opinion about Hamilton. The question is never resolved — Larry goes for a second time and again falls asleep. One wonders just a little how Miranda was convinced to participate in the whole affair. (The same executive producer who, shades of Sarah Huckabee Sanders, testified to David’s 100% attention, told The Hollywood Reporter that “Lin was totally in when we pitched him, and he was so happy to play a different version of himself, [one] very happy to get in Larry’s persnickety sandbox and get dirty.”) Season 9 may be Curb’s most Latino season ever thanks to these closing beats (which include a side-thread involving Larry’s Mexican office handyman). But the diversified palette comes primarily in the form of Larry’s stupendously grasping Puerto Rican guest star, who is entitled in the way that only successful people of color are depicted. (His fictional cousins, meanwhile, are presented as grating, entitled super-hipsters.) Even though he is effectively doing Larry a favor, Lin-Manuel’s leverage and his exercise of it come off as undue. There will remain something unearned about this cameo to the very end, something unprocessed, exterior to Curb’s frame.

In a sense, the bulk of this season — Larry’s putative offense to the sensibilities of 80 million Iranians and some portion of the world’s 200 million Shia, his dinner with Salman, his reencounter with Shara, his trial and retrial — represents a sort of head-fake, setting up a question that it doesn’t quite dare to ask, which might be summed up as the question of whether it is permissible in certain circles not to love Hamilton. If there’s an object lesson in the workings of what might be called multicultural neoliberalism, it is the notion that Hamilton, attended firsthand by at best some 450,000 mostly rich, mostly elderly, primarily white worthies, constitutes an unalloyed good for everyone else. To abstain from that opinion is to risk any number of offenses against all manner of things, mistakenly or not. Against hip hop as a heuristic. Against color-blind casting. Against the specific prosperity of the enterprise’s cast and crew. To suggest, as David quite literally does, that Hamilton’s white fans extol it the way some people share links on Facebook — without clicking, reading, or comprehending — risks offending Miranda’s talent, as well as the myriad aspirations of those who, sight unseen, have chosen to invest in him.

That David should risk such a thing, however offhandedly, while Larry remains mum? This is Season 9’s great failing. Once upon a time, David might have spoken some of this in Larry’s voice, but now the show cannot even bring Leon to say it. Instead David conspires to have Miranda perform a kind of implicit, attenuated auto-critique. History may well judge Hamilton a great work, but its status in Curb is the inverse of the status of, say, Wagner’s music. The play beloved of Obama and Cheney alike can only be spoken well of, while Larry’s affection for Hitler’s favorite composer is at best a little off, at worst proof of race treason.

In the case of Wagner, Larry actively refuses his duty to despise. Recall his rejoinder to his neighbor, the conductor’s baton in Larry’s hand, leading the performance on his antagonist’s lawn. It’s an indelible scene, astounding in its audacity, joyful in its depiction of what could be construed as a symphonic cross-burning. Is there a better, more terrifying, example of the committed intellectual at work? David conscripts art and anger, making of each a kind of soldier; he trips headlong into the fray, risking as much as a fabulously wealthy white man could be said to risk.

That was then. This season, near the end of the final episode, Curb restages a bit from Hamilton — Alexander Hamilton’s famous duel, this time fought with paintball guns. Lin-Manuel is cast in the title role, while Larry stands in for Aaron Burr. It does not end well for either man, but Lin-Manuel gets the worst of it, a paintball to throat. Larry swears it was an accident, but as the mufti might say: what choice did he have?