Istanbul

Scramble for the Past: A Story of Archaeology in the Ottoman Empire, 1753–1914

SALT Galata

November 22, 2011–March 11, 2012

A jumble of pots and bowls lay on the ground along a back wall of the basement at Istanbul’s new SALT Galata, part of “Scramble for the Past: A Story of Archaeology in the Ottoman Empire, 1753–1914,” one of the institution’s three inaugural exhibitions. The faux authenticity of the display reminded me of those tableaux you find at folksy, child-friendly historical sites like Colonial Williamsburg or Istanbul’s own military museum — “How the Slaves Lived,” or “How the Turks Conquered Constantinople.” At first, the scene seemed out of place at SALT, a sleekly designed and modern space, all gorgeous marble, abundant light, and unassuming style.

And yet somehow those dusty bowls fit right into SALT’s ambitious enterprise. Among its countless mandates is to fill in the blanks of Turkish art history — and of history, period. The artifacts along the wall were part of the installation Dig Culture, for which the American artist Mark Dion used photographs to recreate a German archaeologist’s 1871 excavation of Troy. As a photograph, the illegal excavation looks like… well, ancient history. But staged here, the looting feels very much like an ongoing process. In fact, the building that houses SALT, the former headquarters of the Ottoman Bank, inspires a similar haunted mood as you enter: replicas of the Elgin Marbles line the stairs above your head like angels, and an enormous picture window frames the dingy, lovely rooftops of the old Ottoman city. They mournfully return SALT’s gaze, as though they, too, fear being left behind. “Scramble for the Past” isn’t just a story of the Ottoman era; it’s a tale of modern Turkey as well.

The relationship between the Turkish republic and the Ottoman empire remains vexed some ninety years after empire’s end. In his memoir Istanbul, Orhan Pamuk evokes the empire as some sort of phantom limb, an achy reminder of former greatness. But for most Turks born in the decades since World War II, any pride of empire was brainwashed away by the exultation of the nation — of Ataturk, of the army, of the great and singular Turkish state. Whatever connoted Ottoman — Islam, pluralism, one or another antiquity — was denigrated.

The past decade, though, has witnessed an erosion of the great Kemalist firewalls. The ruling Islamic conservative Justice and Development Party continues to revere Ataturk even as it casts off the isolationism and xenophobia that long kept Turks out of the Ottoman sandbox; these days Turks are doing business in Tripoli and Tokyo and sticking their noses in every conflict in the Middle East. The new Turkey, many have begun to say, is a star ascendant, a neo-Ottoman Turkey, with Erdogan as its swaggery sultan-in-chief.

Yet “Scramble for the Past” doesn’t portray an omnipotent Ottoman empire; if anything, it will remind Turks that, long before they were snubbed by Europeans, they were being robbed by them. In the show’s catalog, one finds Raymond-Jean-Baptiste Verninac de Saint-Maur, commanding officer of a ship specially built to transport the Luxor Obelisk to France, reflecting on the nobility of looting. “By stealing an obelisk from the ever-rising soil deposited by the Nile, or from the savage ignorance of the Turks,” he wrote, “France has earned the deserved thanks of the learned of Europe, to whom all the monuments of antiquity belong, for they alone know how to appreciate them. Antiquity is a land that belongs by natural right to those who cultivate it in order to harvest its fruits.”

Still, the exhibition doesn’t treat the Ottomans as mere victims, either. The European plunderers were most often authorized by the empire; it was Mehmed Ali Pasha, Ottoman governor of Egypt, who let that obelisk go.

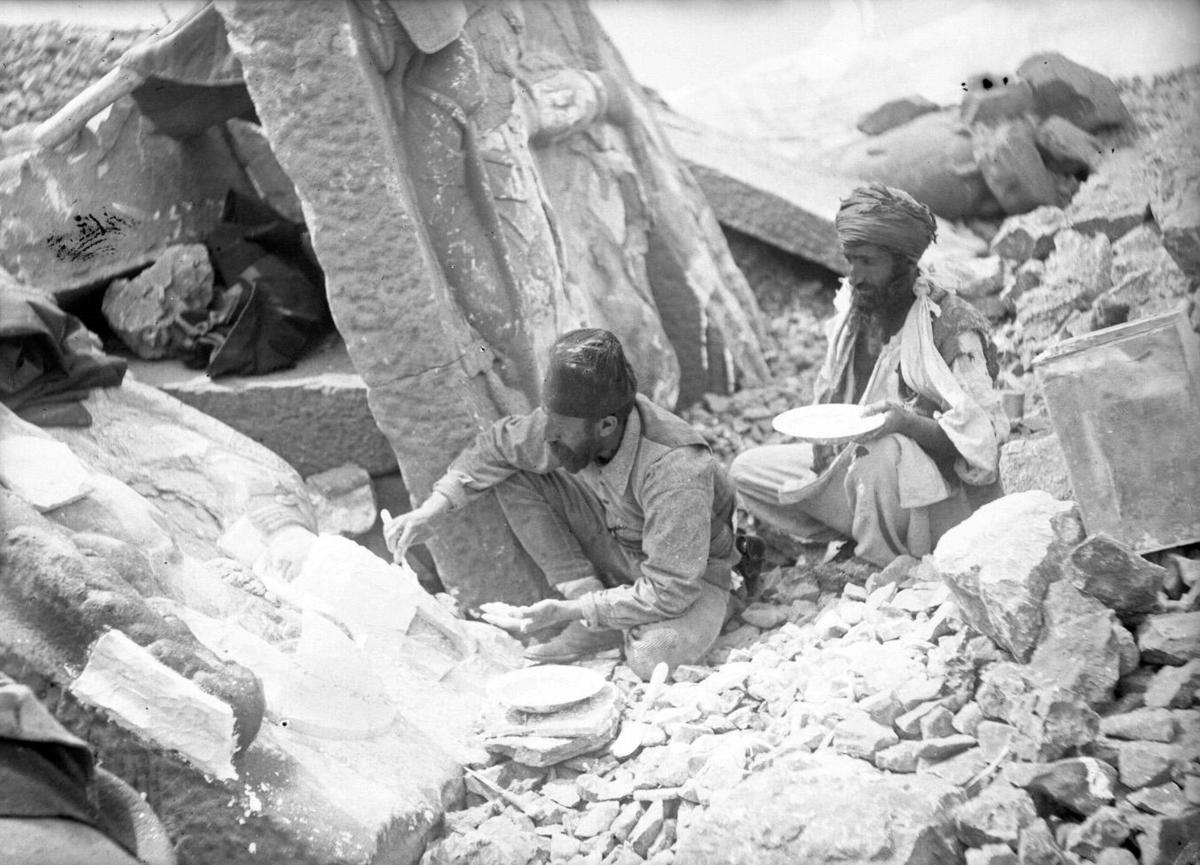

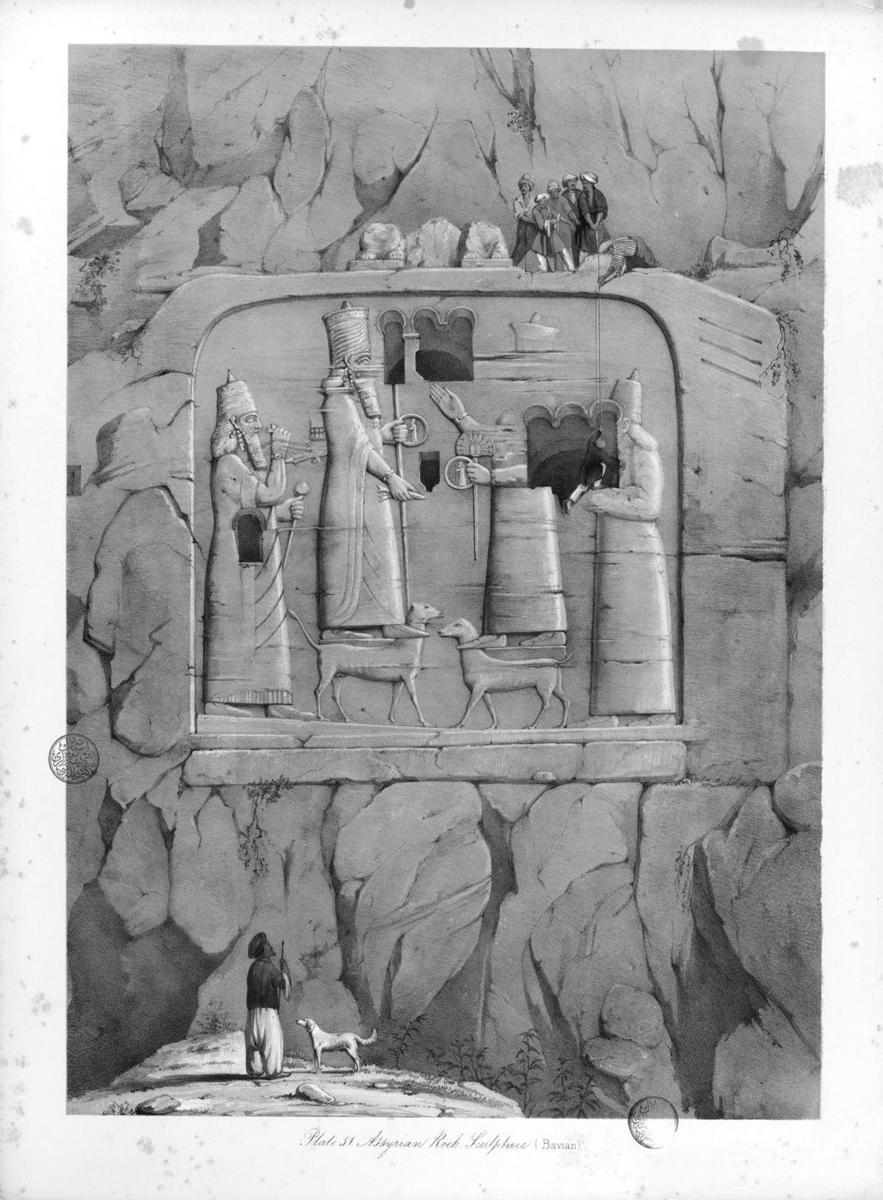

“Scramble for the Past” occupies a large rectangular room on the windowless lower level of SALT. In various cases, curators Zainab Bahrani, Zeynep Çelik, and Edhem Eldem showcase old travel books by Englishmen and Germans, as well as drawings and paintings and records of the explorers’ rediscovery of ancient sites. In one case, a 1789 painting by Jean Baptiste Hilaire portrays ships departing old Istanbul with fragments of the Acropolis, a gift from Sultan Abdulhamid; another case displays part of Napoleon’s Description of Egypt; and another contains a portrait of the queen of Armenia and some drawings of Damascus. Two videos play on a continuous loop: one treating the 1881 discovery of Mount Nemrut in Anatolia, the other about Baalbek in Greater Syria. Running along the walls is a timeline that relates the history of archaeology in the Ottoman Empire.

Like Dion, artist Celine Condorelli was commissioned to intervene upon the proceedings; she designed the support structures for the books and paintings and artifacts to resemble rooms she’d seen before. Some look like the sort of old glass-and-wood cases you might find in an old Englishman’s library, while others have huge swinging doors. One mimics the cutout shape of a church window. These structures cast shadows across the timeline, often marking the onset of a new period in European archaeological excavation. The real beauty of Condorelli’s installation is the experience of following the timeline around the room: the shadows slant ahead of the cases and the artifacts, seeming to move forward in time — as if not only years but darkness, too, is racing ahead of you. This subtle feeling of urgency is braided into the exhibit, which might otherwise seem tame, bordering on staid.

The exhibit begins with the opening of the British Museum in 1753, which inaugurated the age of scientific archaeology in Ottoman lands, and the establishment of the Museum of Administration of Pious Foundations in Istanbul in 1914. But the timeline on the walls doesn’t end with the museum’s opening, as the title of the exhibition might imply — the Turks don’t even get that small triumph. It ends with the outbreak of World War I, when all that newfound potential for preservation was abruptly lost.

The timeline comes as a judgment and a warning. That the Turks more or less allowed the Europeans to dismantle their ancient sites recalls Turkey today: the disregard for Byzantine and Ottoman antiquities, the destruction of Armenian and Greek churches and schools, the belittling of history and facts. The twentieth century arguably saw more violent interruptions than the previous one: coups, wars, the disintegration and obliteration of vital intellectual and artistic communities. And, above all, the specter of Kemalism, which demanded the death of the old for the creation of the new. Preservation did not rank high among the Kemalist priorities; the present-day dearth of museums in Istanbul, a city of fifteen million, confirms as much. If Scramble for the Past is a recovery of one part of Turkish history, then SALT itself pledges to recover another.

Another contemporary piece included in the exhibition seemed to do a little of both at the same time. In For What It’s Worth, the artist Michael Rakowitz asked Istanbulites to contribute objects that meant something to them — things they believed were archaeological artifacts — and assembled them on small intersecting tables. Melisa Sevis, fourteen, contributed a marble that belonged to her grandfather; Esra Bicim, a pendant portrait of Mary, mother of Jesus; Onur Ceritoglu, some crumpled 1970s state-produced cigarette packages he’d found under the floorboards while renovating his house. The objects will make up a “growing permanent collection at SALT documenting archeological history and the ways Istanbulites think about memory and the past.” In exchange for these temporary donations, Rakowitz gave his participants two one-lira Ottoman bills: one to keep for themselves and one to distribute. As he explains in another box on the wall, the short-lived one-lira note was the only currency to include on its face all three languages of the empire’s main ethnic groups: Armenian, Greek, and Turkish. The bill expresses a different Turkish ideology, the one that did not survive.

But by circulating these notes once more, sending them out into the world, Rakowitz seems to suggest that Turkey’s history might yet inform its future. His exhibition is an invitation to the citizens of Istanbul; to those whose memories have been robbed, it’s an invitation to participate in reconstructing their own history. In this way, too, “Scramble for the Past” is an urgent welcome for this contemporary institution devoted to a nation and its vexed relationship to the past. Better late than never.