The story of “the permanent exhibition of arts and crafts and cultural heritage of the captives of the holy war and their ways of living, hygiene, and treatment,” goes back to the early years of the Iran-Iraq war, with the establishment of what was intended to be a temporary camp for Iraqi prisoners at the Heshmatiye military base east of Tehran. In those days, Heshmatiye was a beautiful place, with flocks of birds and tall trees. It was not at all like a POW camp as you might imagine it, not least because the soldiers had not been specially trained to deal with prisoners of war, which seems to have made it easier for friendly relationships to develop between guards and captives.

Among the early arrivals was an artist named Ostad Monghaz. Monghaz had been a professor of sculpture and painting at a university in Italy. The unlucky professor, who returned to Iraq to see his family, was forced by the Ba’athist regime to go to the frontlines for propaganda purposes. During his initial interrogation at Heshmatiye, it became clear that he had no political record in Iraq and had simply been caught by accident. But war has its own rules, and the professor had entered the camp as a prisoner. There wasn’t much that could be done for him. Still, Monghaz managed to make art in the camp, thanks to the martyr Mohammad Ali Nazaran, for whom the base is now named.

At the time, Nazaran was the head of the Prisoners of War Commission and, he created an uncommonly pleasant atmosphere for the captives. Despite the ongoing war, Nazaran somehow secured the necessary permission for the families of many of the captives to come and visit their sons and husbands in Iran. This was exceptional not only in the context of this war, but also in the history of war. His compassion gave the Iraqi captives hope. Even after his death, his memory was kept alive in the minds of Iraqis.

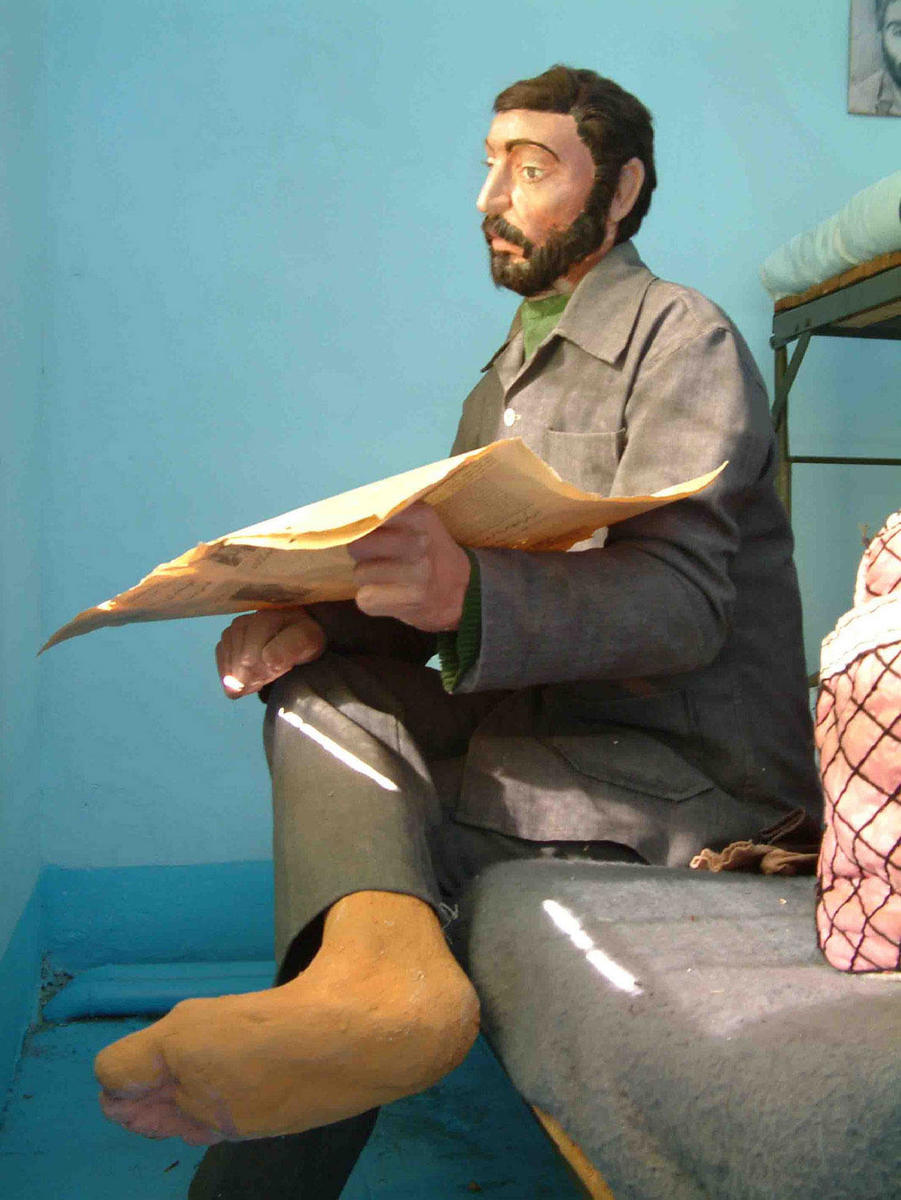

In 1990 and 1991, as the issue of prisoner exchange came to the fore, the question of how and whether to preserve the prisoners’ works was brought up. Over the course of four years, and through evaluation sessions of the prisoners’ artworks by the Committee of the Prisoners of War, those responsible for the camp agreed to build four halls, containing sixteen rooms, to exhibit and preserve the paintings, calligraphy, woodwork, needlework, and sculpture produced by the POWs. This was a great victory for the captives who came to this camp in their youth and now had to leave it. The new museum would showcase the creativity and humanity of the captives — and also of the captors. The camp itself was part of the exhibition. One of the former captives, an aging engineering graduate named Medhat Hosseini, stayed on, building delicate life-size sculptures from available materials — construction plaster, sometimes even dental plaster. These figures recreated life in the camp for visitors. There were even figures of Saddam Hussein or King Hussein of Jordan.

But in the decade and a half since the end of the war, the museum had few visitors beyond Red Crescent representatives, the occasional politician, and tours of distracted schoolchildren on the anniversary of the Iraqi invasion. Most people were unaware of its existence. Over time the number of staff at the museum was cut to a minimum. Soldiers took over the job of cleaning and maintenance, and many of the most powerful works made by the captives were damaged or simply suffered because of poor preservation. These days, Hosseini wanders around repairing sculptures, kept company by an old cat.

In 2008, a huge highway project was announced that would run straight through the museum site. A concrete wall was erected on the eastern part of the base for security purposes. Gone were the beautiful pine trees that surrounded Heshmatiye. Already a large part of the camp is used to collect urban and industrial waste.

Soon after, the Tehran city council passed a law requiring all military camps to be removed from the immediate area. Today the museum is awaiting its destruction.

Soon, beneath a mass of dust and concrete and the yellow lights of the highway billboards, the stories of 57,000 Iraqi soldiers who once lived on these grounds will lie buried and forgotten.

In 2007, Vahid Zare Zade directed a short film about the museum called POW 57187.