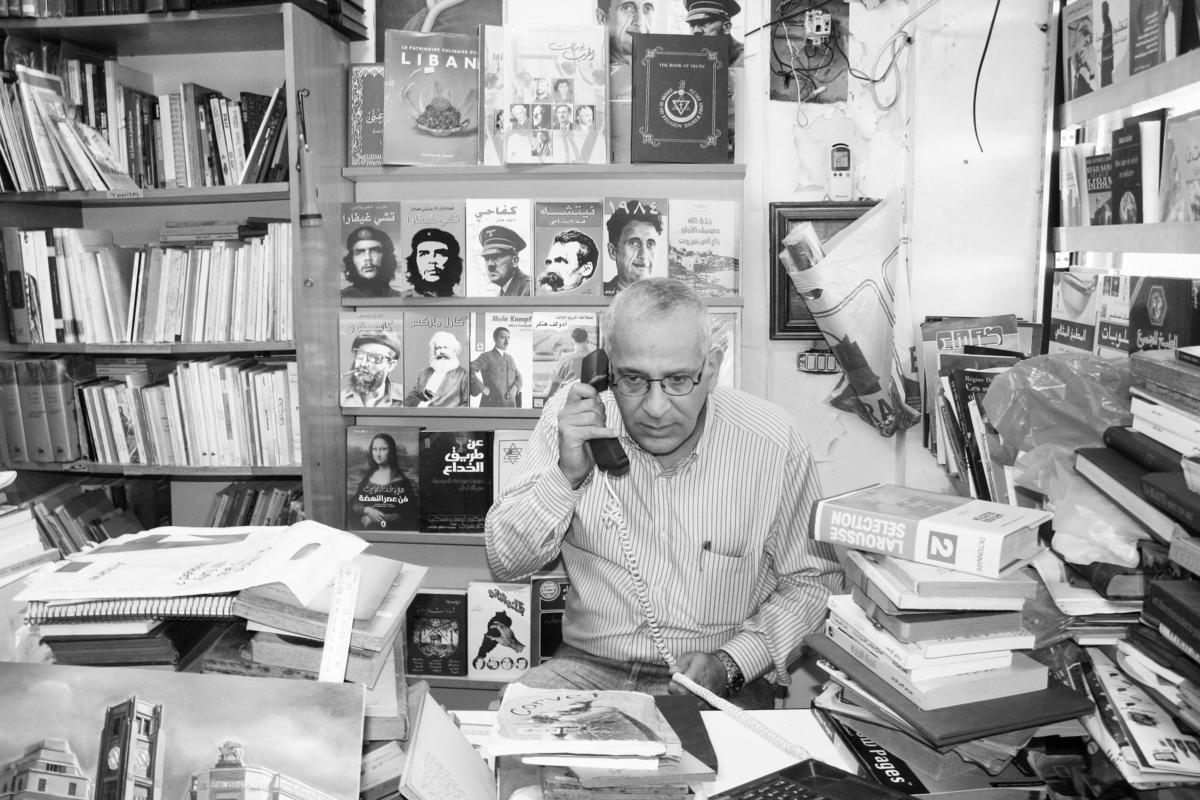

Last year, Bidoun took a field trip to Beirut to attend the Home Works Forum hosted by Ashkal Alwan, to collect phrenological data, and to go book shopping in preparation for our PULP issue. The books, magazines, and pamphlets that would appear in that issue came almost exclusively from two West Beirut bookstores owned by one man — Omar Sleiman.

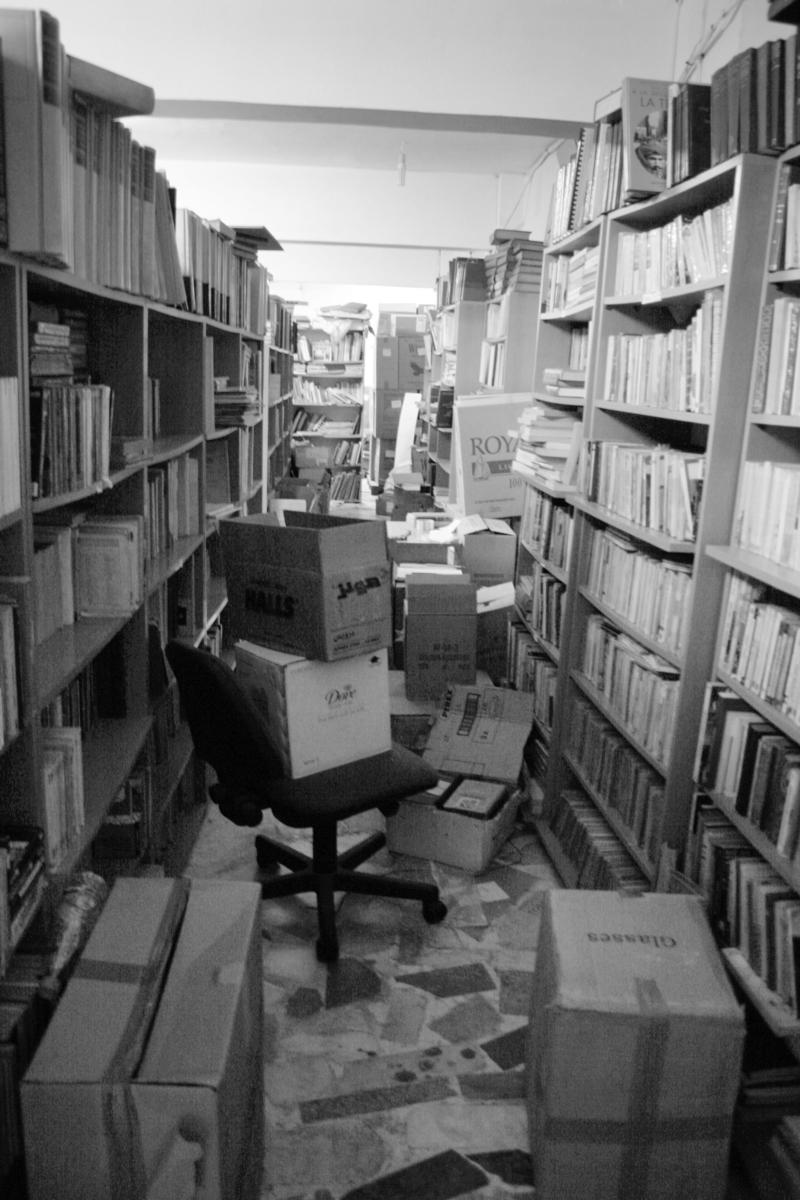

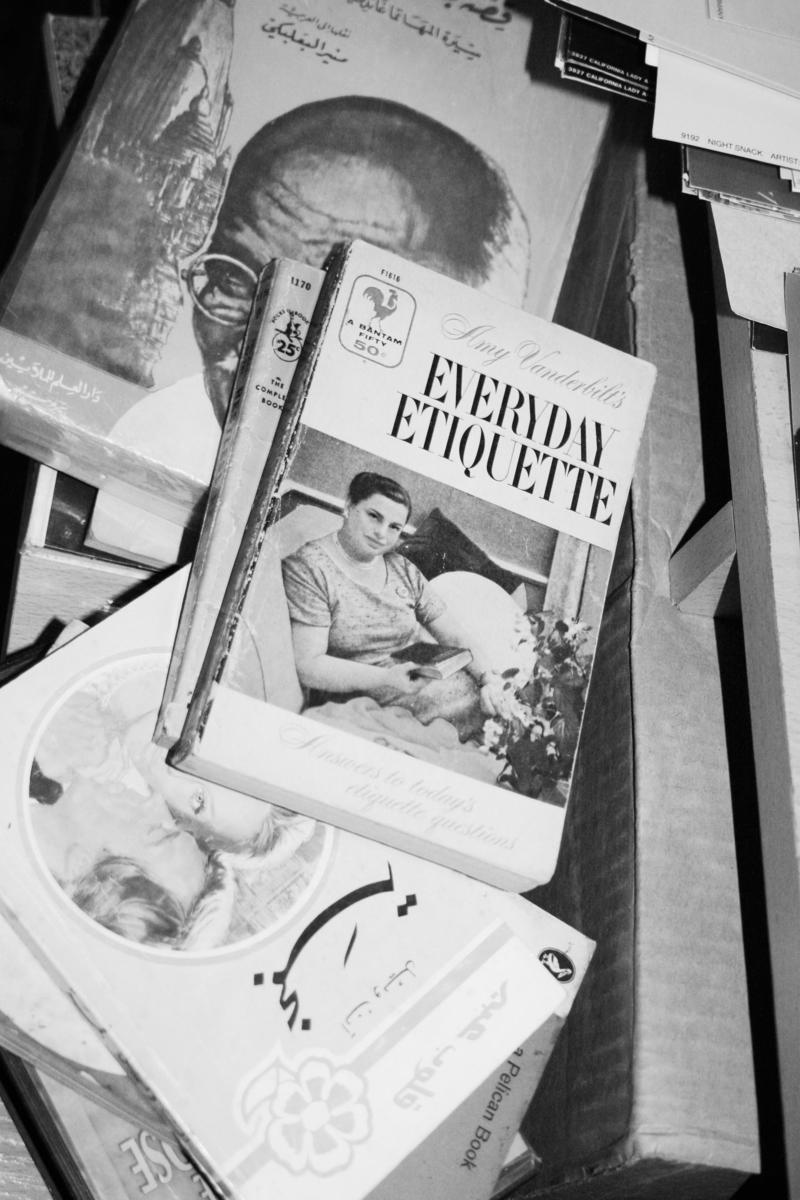

Sleiman’s stores are a dying breed. One doesn’t enter a store like this looking for a specific volume. Instead, the book finds you. Order and disorder intermingle in a way that seems to discredit both. Books are organized by size and format — or else by subject matter — sometimes vertically on the ground, other times horizontally on shelves. And there is, of course, a basement.

Within the disarray, an ethos is at work, and it’s one that is arguably more democratic and more true to the nature of the history, memory, and gestalt mode of cultural production that books are supposed to represent than of any Dewey decimal. Here, there is a small and particular collection of political books translated into Arabic, which Sleiman publishes himself. These books, with their clumsy clip-art covers, happen to appear in the front windows of almost every bookstore in West Beirut. They represent a strange constellation: 1984 by George Orwell, The Antichrist by Friedrich Nietzsche, Das Kapital by Karl Marx, Mein Kampf by Adolf Hitler, The Protocols of the Elders of Zion, and the Kabbalah. Bidoun sent Lana Daher to Book Bazaar to talk shop and try to learn more about where this peculiar canon is pointing, and why.

Lana Daher: Do you collect things at home that you don’t share with the store’s clientele?

Omar Sleiman: Anyone who owns a bookstore — especially if it’s old — has a private collection. The collector doesn’t know what he wants to do with this collection, but he knows that it would be a shame to sell the books in it or give them away. I don’t know what I’ll end up doing with my books, but I would never sell them.

LD: Do you at least share them with friends?

OS: I don’t show them to people, because if I do, they’ll want to buy them, or get them one way or another. I don’t let anyone visit me at home. I have around two thousand books there, each one organized in crates or on shelves.

LD: Are there things that some people buy more than others?

OS: No. You give customers a huge collection to choose from, and they leave with one book. There is no money in the book business.

LD: Do you find people are reading more or less these days?

OS: I’m not talking about reading, I’m talking about buying. When the situation in the country is good, they buy. After Hariri’s assassination and the war in 2006 and the events of 2007 and those of May 2008… all of these situations have affected the economy. In the past four years, in Hamra alone, ten bookstores have closed down, among them some very important ones, like Nawfal and All Prints and Maktabat Ras-Beirut. Many others are practically closed down but have not made it official yet. Of course, these stores are also closing down because people just don’t read anymore.

LD: When did you open this store?

OS: I’ve had an interest in collecting since 1974, when I started buying books in France, where I lived for six years. I used to buy books and send them to Lebanon. But the idea of opening a shop didn’t really mature until sometime between ’95 and ’98. By that time, I had crates filled with books, and I had no more room for them.

This shop opened on September 4, 2001, seven days before September 11. You know, I predicted that event back in July 2001. I knew that on September 11 something massive would happen, but I didn’t know what. I thought something would happen in Lebanon, though. I thought that there would be inflation, that the Lebanese lira would drop and the value of the dollar would increase. So I advised all of my friends to exchange their money and convert it to dollars, which they did. But as we know, what happened on September 11, 2001, had nothing to do with inflation or the Lebanese lira.

LD: Have you ever inherited books from anyone?

OS: Yes. My sister once wanted to throw out some books. I put them inside of the trunk of my car and went off to sell them. Before selling them, I skimmed through the stacks and selected a few for myself. One of them is my most prized book, The Road to Authority, by Fouad Awad. This book truly touched me. He was responsible for the revolution, or the attempted coup by the Syrian Social Nationalist Party in 1961. He wrote the book after spending ten years in jail, after they tortured him and fucked him and his comrades. In this book, he explains how the coup attempt went wrong.

When I read The Road to Authority in the early ’90s, I was a major in the army. I was shocked. I felt cheated. I couldn’t understand why I knew nothing of this story. Something historic had taken place in the army and in my country, and I had never even heard of it. I had never heard of Fouad Awad either. Maybe the coup attempt was a mistake. That’s just a matter of opinion. But whether it was a mistake or not, it resulted in the condemnation of tens of thousands in ’62 and ’63. I couldn’t believe that I hadn’t heard of this event. Isn’t it my right to know what happened in the army? Could the Lebanese army be without memory? This shocked me. I realized I needed to read, or I would never know anything.

You see, when I started to collect books, I stopped reading them, especially after I got my engineering degree from France. I was studying textiles and chemistry in Lille from 1974 until 1980. I used to think that the limits of the world were one’s major in college, and I mostly read technical books on topics related to my field, though I would still collect the rest.

LD: Were you collecting books during the Lebanese Civil War?

OS: Of course. I never stopped. When I returned to Lebanon, I became a lieutenant in the army. At first, I was single, and my pay was meager. It barely covered my expenses, and there was no way I could afford a house on my own, so I lived with my parents. Then there was the chaos of 1980 and ’81. I was still in the army, and in 1982 and ’83, my salary increased, thanks to General Tannous. Then there was the intifada in 1984, and my salary went through the roof, jumping from $300 to $1500 per month. Later that year, political parties began to take over the area… and there was inflation. By 1986, my salary had fallen to $20. But there were always a lot of books available for cheap — and no one was reading, so book merchants were selling at low prices.

LD: What do you read now?

OS: Well, I don’t read technical literature anymore. I stopped reading that sort of thing in 1995 — six years before I left the army as a colonel. Since then I’ve been reading history, philosophy, politics, and a little bit of psychology. I also read Le Point, a weekly magazine that I’ve been collecting at home for nine years.

LD: Do you feel you have any competition now?

OS: The field has no competition, because there are no customers. When there are a lot of clients, you can fight with your neighbor over them, but now there are no clients to fight over. Big companies are monopolizing the market, and what the little people are fighting over is just the remaining 20 percent. In Lebanon there’s also a linguistic problem. When you say “bookstore” (maktaba), people think you sell stationery. This is the Lebanese population for you! If they find books in a bookshop, they are surprised. When I started to sell books, people told me to sell stationery, too. Without newspapers, magazines, and stationery, you won’t make any money, they said. But I refused.

LD: Do you ever buy books because they’re aesthetically appealing?

OS: I don’t buy things because I’m attracted to them. I buy what I think my customers will be interested in. One book is popular this month, I get a stock of it. Then next month it’s dead. Every once in a while, political books get popular, so we translate and publish them. Then all of a sudden, no one wants to read them anymore, they completely die, so I’m stuck with an overstock. I don’t understand it. I should just make my predictions. I work with numbers.

LD: Is this kind of predicting something you’ve done since you were young?

OS: No. But since 1998 I’ve been predicting all kinds of events based on numerical proofs related to past events.

LD: Does it work?

OS: Sometimes yes, sometimes no. But people get stupefied — they always come back when it works. Of course, they also come back to tell me when it doesn’t work. I predicted Hillary Clinton would win the American election. People came back to tell me that I had lost and Obama had won.

LD: What was your last prediction?

OS: I can’t tell you.

LD: Do customers ever buy books that make you roll your eyes?

OS: I am vicious, very vicious. I have no taboos. Sex, erotic novels, porn. I read porn. Every once in a while I enjoy reading an erotic novel. I don’t draw a line between good and evil, and what I allow myself, I allow for others.

I don’t like poetry. I don’t know how to evaluate it or estimate its price — it means nothing to me. So I don’t get much of it, unless it’s in high demand among university students. But now they all photocopy everything. I don’t think they know that they can get the books from my store for even cheaper than the photocopies.

LD: You should advertise that fact with a poster. I can do it for you.

OS: No, I’d rather not. It’s their own problem if they don’t know. People don’t know anything anymore. They don’t understand marriage or politics or anything, because they don’t read. And their parents didn’t teach them anything. Thirty or forty years ago, mom and dad used to teach their children everything they knew, but now they rely on schools. Mothers work and can’t be bothered to spend time with their kids at the end of the day, so they put them in front of the TV.

You sleep for eight hours, work for eight hours, commute for an hour, eat for two hours, and there are five hours left. What do you do in those five hours? TV from 7 to 11. Poison hours of propaganda.

How does reading decrease? You add distractions to the world. You can’t even speak in restaurants anymore, because you can’t hear the person sitting in front of you. The transmission of knowledge takes place through words, and they are trying to drown out words, and our voices, with these distractions.

LD: Tell me about the books you publish.

OS: I choose them based on my own political feelings. All the books that I translated and published had a big bang; they started a revolution in this city. I prepared the titles, published them, and they became number one in the Arab world. They include The Gambler by Dostoevsky, The Prince by Machiavelli, The Jewish State by Theodor Herzl, The Protocols of the Elders of Zion, and lots more.

You know, reading keeps you away from obsessions and rumors, which are some of life’s many traps. I used to be obsessive about conspiracies. I used to be sick and depressed. Then they discovered that I was psychosomatic. I went to many doctors, but eventually I saved myself by reading Health Makes Miracles, Gaylord Hawerz. That book saved my life.