Amman

Mona Hatoum

Sahel al-Hiyari

Darat al-Funun

September 12–November 27, 2005

There is a vague animosity among artists, curators and critics in the Middle East reserved for Mona Hatoum — a mix of envy for her fame and resentment for what is perceived as her tendency to market her “otherness” by reducing it to apolitical, ornamental gesture. But opportunities to critically engage her work — as physically present, not endlessly reproduced — are rare in the region. Rarer still are exhibitions of her early, experimental videos.

Before the ubiquity of her sculptural work — all those kitchen utensils made massive and menacing — Hatoum began her career as a spiky performance artist in a similar vein as Karen Finley and Janine Antoni. From smearing her naked body with clay to using an endoscopic camera to explore her every orifice, Hatoum moved from video as documentation to video as form in the 1980s. Much has been made of ambiguity in her work. In her sculptures, that ambiguity is a quick and easy punch line (look, it’s a huge mouli julienne, scary!). In her earlier videos and performances, ambiguity manifests itself in technological innovation and a refreshing crudeness of form. These works are messy, untidy things — and compelling to behold.

Darat al-Funun in Amman has two early videos in its permanent collection, So Much I Want to Say (1983-) and Measures of Distance (1988). This fall, the foundation mounted an exhibition to support the first public screening of the former (It was the first time Hatoum’s work had been shown in Jordan at all).

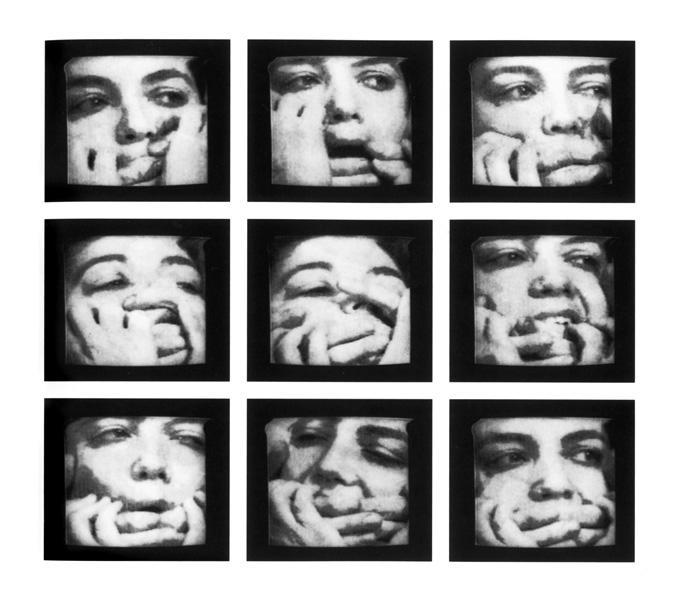

Recorded as a satellite transmission of a slowscan exchange between Vancouver and Vienna in 1983, So Much I Want to Say features Hatoum’s voice repeating the title line at an even speed, while an image of her face and a woman’s face being gagged by a man’s hands freezes and updates in a top-to-bottom sweep every eight seconds. Her expression shifts with each sweep, from fear to desperation to defiance, suggesting the trace of a narrative but leaving it caught like a stutter in the throat. The disjunction between sound and image suggests dislocation, separation, the impossibility of bridging distances and communication breakdown. The video makes use of technology but at the same time exposes its failures. That it looks and sounds so dated now adds another layer of resonance — how quaint the slowscan in an age of Skype.

Sometimes a shift in the geographic context in which an artwork is shown is only additive and not constitutional. To bring Hatoum’s work to Jordan may dull some of the western art historical references (such as her debt to ’70s era feminist performance artists, Surrealism and Duchamp), without losing much. But a shift in sociopolitical context works the other way around. Darat al-Funun director Suha Shoman hasn’t shown Measures of Distance publicly, at least not yet anyway, perhaps because an audience of Arabic speakers will be able to pick up on nuances that are inaccessible to non-Arabic speakers. Shoman worries that those linguistic nuances may be problematic.

The mesh that makes up Measures of Distance starts with Hatoum’s voice over narration as she reads an English translation of an epistolary correspondence with her mother about when Hatoum photographed her body and recorded her voice in the bathroom of their home in Beirut, an incident that outraged Hatoum’s father. On screen are the nude photographs, overlain with the text of the letters in Arabic (a layering that could, of course, be read as overly or cheaply exotic: a veil of script that reveals as it obscures, a gesture that may well detract from the work in dulling its bluntness).

Behind all this is the initial conversation, also in Arabic but untranslated and unsubtitled, visceral in its discussion of sex and marriage, men and women, parents and children. To grasp all of these elements at once adds new meaning and fullness.

Simultaneous to the Hatoum screening, Darat al-Funun held a smaller exhibition for the architect and artist Sahel al-Hiyari. Born in Damascus, based in Amman, Hiyari recently completed a major renovation to the foundation’s exterior facade. Made from steel and concrete, it adds a decidedly contemporary layer to a site with ruins dating back the sixth century. To celebrate the new facade, he built a room to showcase ten years’ worth of architectural projects.

Painted entirely black, the room houses a series of back-lit filtered (layers removed, put on film like a transparency or negative) drawings along one wall and an arrangement of stark white maquettes of architectural projects, buildings, houses and more along the other. Both rows seem to levitate in the space, highlighting line and composition on one side, form and volume on the other.

Hiyari is unique among his peers in his modesty (working with low budgets and self-imposed limitations), his desire to recycle existing building stock (meaning a necessary engagement with the shabby concrete blocks that characterize Amman’s rapid urbanization), and his insistence on nesting his buildings into their environments. At a time when most architects are bent on erecting signature icons, Hiyari is building, for example, a low-lying house in North Yemen with a shape congruent to the surrounding hills, and a pair of midrise apartment buildings in Kuwait City marked by a double façade of aluminum panels. In the end, the diversity of design solutions on view served as an object lesson on a range of regional architectures and provided for a telling insight into Hiyari’s creative process.