Mohamed Soueid describes his interview style as a cross between a police investigation and a psychotherapy session. On occasion, he might talk to his subjects for two, four, even six hours — to the point where the experience verges on painful for his subjects. He is drawn to narratives of death, loss, disappointment, disillusionment, and regret. He makes people laugh and cry, boast and tell jokes, perform and ultimately disarm. Like a detective or therapist, he waits, listens, and takes his time. At fifty-one, he is strenuously patient. He might shoot up to forty hours of video footage for a film than runs less than an hour from beginning to end. He considers the act of editing a process of writing, that’s where his authorship emerges. His films are cinematic essays that play with the languages of documentary, fiction, and experimental video. He rarely tells a single story, opting instead for a tangle of narrative threads.

In How Bitter My Sweet, from 2009, for example, Soueid follows several strands at once, assembling a cast of six characters from almost as many Arab countries. He rides from one side of Beirut to the other with a pensive, soft-spoken taxi driver; lingers over tea with the bombastic, self-styled archivist of Saida; listens to music with a shy jewelry designer; goads a loquacious housewife into telling him what a beauty she was in her day; and brings a shopkeeper to tears by probing his relationship with his dead brother. There’s little to no relationship from person to person, yet their stories collectively touch on themes related to migration and belonging.

Soueid is widely regarded as Beirut’s first video artist, the pioneer and progenitor of the wide-ranging, deeply probing visual experimentation that has made the city such a hub for video production over the last twenty years. After years of working as a film critic and an assistant director on commercial films, Soueid made his first independent video in 1990. Al-Ghiyab (Absence) delves into the stories of four people who lost friends or relatives during the civil war in Lebanon, though their deaths were pointedly unrelated to the conflict.

The forty-five-minute piece, a tender rumination on life and death, wasn’t shown publicly in Beirut until last year (according to rumor, it was the subject of a financial dispute between Soueid and a company he had hired to do the subtitling). But it was often screened in private, at a time when the city’s contemporary art scene was just beginning to percolate. It profoundly influenced a generation of artists and filmmakers — Akram Zaatari, Ghassan Salhab, and Mahmoud Hojeij among them — as did Soueid’s later work, most notably the trilogy Tango of Yearning (1998), Nightfall (2000), and Civil War (2002).

Born in 1959 in Beirut, Soueid is too young to be the godfather of Beirut’s current contemporary art scene, but he is a serious contender for the role of elder statesman. There was a time when he was frequently lumped into “the group” of artists, writers, and filmmakers from Lebanon who have become known internationally over the past decade. Soueid’s films were programmed into some of the seminal showcase events — Catherine David’s ‘Contemporary Arab Representations’ at the Witte de With in 2002; ‘Possible Narratives’ organized by Christine Tohme and Akram Zaatari for Videobrasil in 2003; ‘Beyond Truth and Fiction’ in Cairo in 2005 — that served to crystallize and codify the Beirut scene. But Soueid never really decamped to, and was never fully embraced by, the art world, locally or internationally.

Soueid fell in love with cinema as a child. He remembers the plot of the first movie he ever saw in a Beirut theater, the Empire Cinema on the eastern edge of the city center, which has long since been destroyed. “It was a western,” he says. “My father took me to see it. You know, it was the kind of western that takes place in a Mexican village. Not a Pancho Villa film, but something like this. It was about a buried treasure. Everyone wanted to find the treasure. The American heroes arrived to the place where the treasure was hidden. But when they uncovered it and opened the chest, they found it was not full of gold, but an olive branch.”

At that time, film criticism was flourishing in Lebanon alongside the rituals of a robust movie-going public. “I used to read a lot about cinema in the newspapers,” recalls Soueid. “The movies used to change in the theaters on Mondays, so new reviews would always appear in the papers on Mondays, as well as in the cultural supplements that were published on Sundays. Film critics at the time were really serving film culture properly. They were writing about New Wave, Neorealism, and they didn’t encourage people to follow fashion or gossip. They covered European, American, and Egyptian cinema. Youssef Chahine was at his best at the time, and you also had people like Salah Abu Seif and Tawfiq Saleh. Later, in the 1970s, the critics started talking about Lebanese filmmakers like Borhane Alaouie and Maroun Baghdadi. And from my childhood I wanted to be a director. I thought that being behind the camera was the most important place to be.”

When Soueid reached university age, the closest thing to a film school he could find was the theater department at the Lebanese University. Since this wouldn’t have put him anywhere closer to that coveted spot behind the camera, he studied chemistry in the faculty of sciences instead. But he dropped out of school a few months before graduation and began working on the crews of features films. “I’m self-taught,” he says with a cringe of modesty.

Soueid also got a job at the pro-Syrian newspaper Al-Sharq and began writing criticism of his own. Later, he moved to the left-leaning As-Safir, where he took over as the lead film critic when Yousry Nasrallah left Beirut, and began contributing to Al-Mulhaq, the weekend cultural supplement of Lebanon’s largest and most mainstream newspaper, An-Nahar. In addition to accumulating decades of experience and clips, Soueid has written a book about films produced during the civil war, a highly personalized history of cinemas in Beirut; and a novel, titled Cabaret Souad and fueled by an oversize obsession with the late Egyptian actress Souad Hosni.

During the fifth edition of the Home Works Forum in Beirut this past spring, Soueid delivered a lovely lecture — curiously described as such, rather than as an artist’s talk — that traced the history of foreign film production in Lebanon during the 1960s and ’70s, against the backdrop of Soueid’s fascination with actresses such as Hanna Schygulla and Jane Birkin, and his enduring affection for a city he saw refreshed in their eyes. Jumping from Volker Schlöndorff ’s Circle of Deceit to Delta Force, 24 Hours to Kill, The Man with the Golden Gun, Marlon Brando, the disappearance of Mussa Sadr, and an indefatigable Greek singer who was kidnapped in Lebanon in the 1980s, Soueid created a web of wild associations: “We cannot look into things with an investigator’s or a detective’s eyes,” he said. “Things converge that have nothing to do with one another, but then somehow it all makes sense in the end.” If nothing else, this was an incredibly apt description of all Soueid’s work to date.

What is striking, however, is that despite Soueid’s intense love of cinema, he has only ever shot video, never film, and he seems completely uninterested in making features. He tried once, in 1986, but the shooting was repeatedly interrupted, his producer bailed, and the lead actor left the country. “It was a bad experience,” he says, a characteristic understatement. He still has the footage, under the working title Merry Go Round, on U-matic cassette tapes, the first video format available in Lebanon. “I never had the financial means for shooting on film,” he says. “I always worked on underground films, so video was kind of my savior.”

Soueid did spend several years working on other people’s feature films, and in 2003, he collaborated with Egyptian director Yousry Nasrallah in adapting Elias Khoury’s Bab al-Shams to the big screen (a four-and-a-half-hour epic). But overall, he says, “I’m still in love with the documentary approach. It’s therapy, and I need it. I’m very attached to the street. It’s where I can experiment.”

Soueid’s work is prone to dwelling on themes of love, sex, longing, and sorrow. These are the gritty bits of emotional life that are so often absent from the work of his most immediate peers. In the art world more generally, they’re also the subjects that tend to be anaesthetized into oblivion, abstracted in the prevailing lingo as affect, a lame and increasingly overused term that has become a catchall for anything earthbound and messy. Soueid is also somewhat unique in that he doesn’t shy away from issues of socioeconomic class, that elephant in the room of Lebanese contemporary art, nor does he avoid gut-wrenching grief.

“I come from popular culture,” he says. “I still live in the old quarter of Beirut where I was born. If you live in these popular areas, you receive sounds and stories. In these poor areas where I live, there are always problems. I have a great love for Egyptian movies and novels. Take Egyptian movies, plus the influence of the women in my family, and you might call it melodrama, though I would call it tenderness. I was never an optimistic guy, even as a child. I remember in school I was very touched by the melancholic stories of French literature, Chateaubriand’s stuff. I remember the teachers who taught us French literature — some of them used to recite poetry, and they would cry. At some point, being melancholic was a kind of fashion.” Still, the stories folded into his first film are pretty harrowing, particularly that of a young girl who died by falling from her window in the middle of the night.

It’s interesting to consider the relationship that Soueid cultivates between improvisation and control. In an interview for the journal Parachute with fellow video-maker Akram Zaatari, he once said he was sensational rather than intellectual in his work, and that if he evoked intellectual issues, he didn’t do so by intellectual means (he was drawing a distinction between his work and that of Walid Raad). But while Soueid allows for a lot of emotional leakage, and follows issues and conflicts as they seep and bleed into one another, he also exerts a great deal of formal rigor.

When he was preparing to shoot Al-Ghiyab, for example, he studied the sunrise, sunlight, and sunset of every location he intended to film. And despite the fact that his work relies on the unpredictable paths of several interviews, he somehow managed to script the entire thing, talking to his subjects in advance without exhausting their capacity to speak naturally and not sound rehearsed.

“When I did Al-Ghiyab, I was coming out of the experience of working as an assistant director on mainly commercial films. I thought these commercial films were made badly. We rarely worked from fully written scripts. Everything was chaotic. The shooting, chaotic. The editing, chaotic. So I suppose in the beginning I thought the best thing to do was not work like this, to have a full script and sketches of everything. So despite the fact that my first film was a documentary, out of the meetings I had with the people who appear in the film, I was able to construct a kind of script. And I shot the film as it was scripted. I wasn’t surprised or embarrassed by the interviews. It was basically people talking to me about their sorrows.”

Like many creative figures in postwar Beirut, Soueid found employment, and room to breathe, in the local television industry. At the end of Lebanon’s civil war, the country’s media landscape was a mess. Every political party worth its salt had a television station of its own; most of them broadcast only slipshod news programs, all highly skewed toward their respective party positions. They filled the rest of their airtime with Egyptian movies and American sitcoms. But starting in the 1990s, the government began regulating the industry and cut more than fifty stations down to around ten. That time equally represented a moment of fleeting optimism and economic opportunity in the region, when it looked like a substantive peace deal might be struck in the Arab–Israeli conflict, and investments flooded into several of Lebanon’s creative industries.

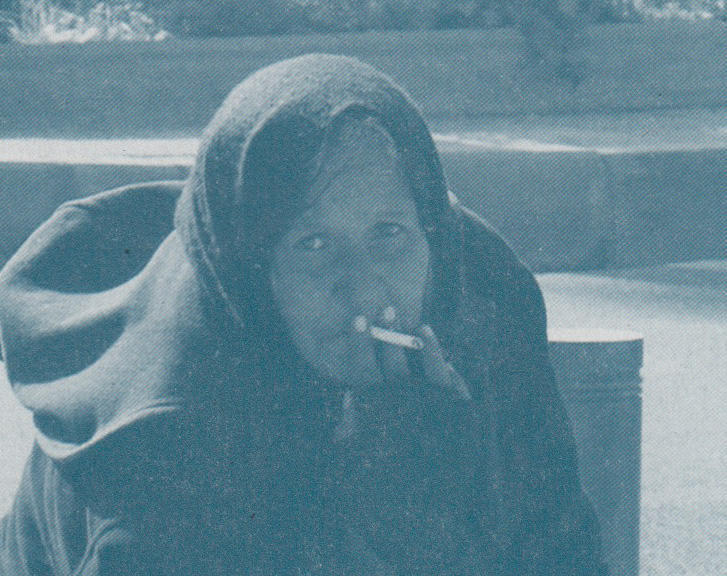

Soueid joined the state-run station Télé-Liban in 1993. He spent the next three years making adaptations from theater, and daring documentaries, such as Cinema Fouad (1994), a sensitive portrayal of a Syrian transsexual — who was living in downtown Beirut at the time; had been a soldier, a servant, and a cabaret dancer; and was saving up for a sex change — that explored identity and desire in the form of a grueling, twenty-eight-minute interview.

For a time, the television industry was aggressively recruiting young talent and providing unfettered access to equipment, along with relative freedom to produce experimental work. But that situation didn’t last long. Akram Zaatari, who worked as the executive producer of a morning show on Future TV, got out of the game in 1997. Rabih Mroué, who also worked at Future TV until just a few years ago, regarded it as little more than a day job. Soueid, meanwhile, is still deeply embedded in the industry.

When he left Télé-Liban in 1996, he often says, he thought his career was finished. But he spent the next six years making the trilogy that in many ways defines him. Tango of Yearning digs into a personal story of heartbreak and obsessive love. In Nightfall, he reunites with colleagues from his days as a member of Fateh’s Student Brigade, for whom fighting in the civil war often meant guarding an abandoned roadside ditch. Civil War, the strongest and most moving of the three, delves into the mysterious death of a close friend, the cinematographer Mohamed Douybaess, who held out a theory that the civil war was caused, at least in part, by sexual frustration.

In 2002, Soueid took a job with the MBC Group. He headed up a documentary division, and now makes films for the satellite station Al Arabiya. One of the downsides of working in television is that he rarely retains the rights to his work. DVDs of his masterful film My Heart Beats Only for Her are widely available, but his name is nowhere to be found. That film — a melancholic portrait of cities such as Beirut and Dubai, poised between the models of Hong Kong and Hanoi — is the second installment of another trilogy, which began with The Sky Is Not Always Above, a winding history of Beirut’s southern suburbs. Both films dig into the subject of revolution and explore the disjunction between the ideologies of revolutionary movements and their practices. Soueid is currently planning the third and final installment, but is reticent about disclosing its subject.

Unusually for Soueid’s later work, My Heart Beats Only for Her was feted with a theatrical release in Beirut last year, thanks to the efforts of Hania Mroue, who directs the art house cinema Metropolis and in 1999 cofounded the film collective Beirut DC with Soueid, among others. (Though supportive of Beirut DC’s work, Soueid is no longer actively involved. Young people still believe in politics, he says, but their politics exhausted him long ago.) Alongside Christine Tohme of Ashkal Alwan, Mroue has been trying to coordinate a retrospective of Soueid’s films for years, an initiative that would necessarily involve restoring some of his older works and subtitling the majority of them. But Soueid isn’t ready to play along. “When I hear the word retrospective,” he says, “the first thing that comes to mind is that I retire. I would have to make a full stop, or end a chapter in my career. I would have to reach a point where I’ve said what I have to say, and that’s it.”