Recently I saw the first scenes of Shahla Khadijeh Jahed’s court defense. Shahla was accused of the first degree murder of Laleh Saharkhizan, wife of famed Iranian footballer Naser Mohammadkhani. This soap operatic affair, which has captured the attention of millions, began more than three years ago.

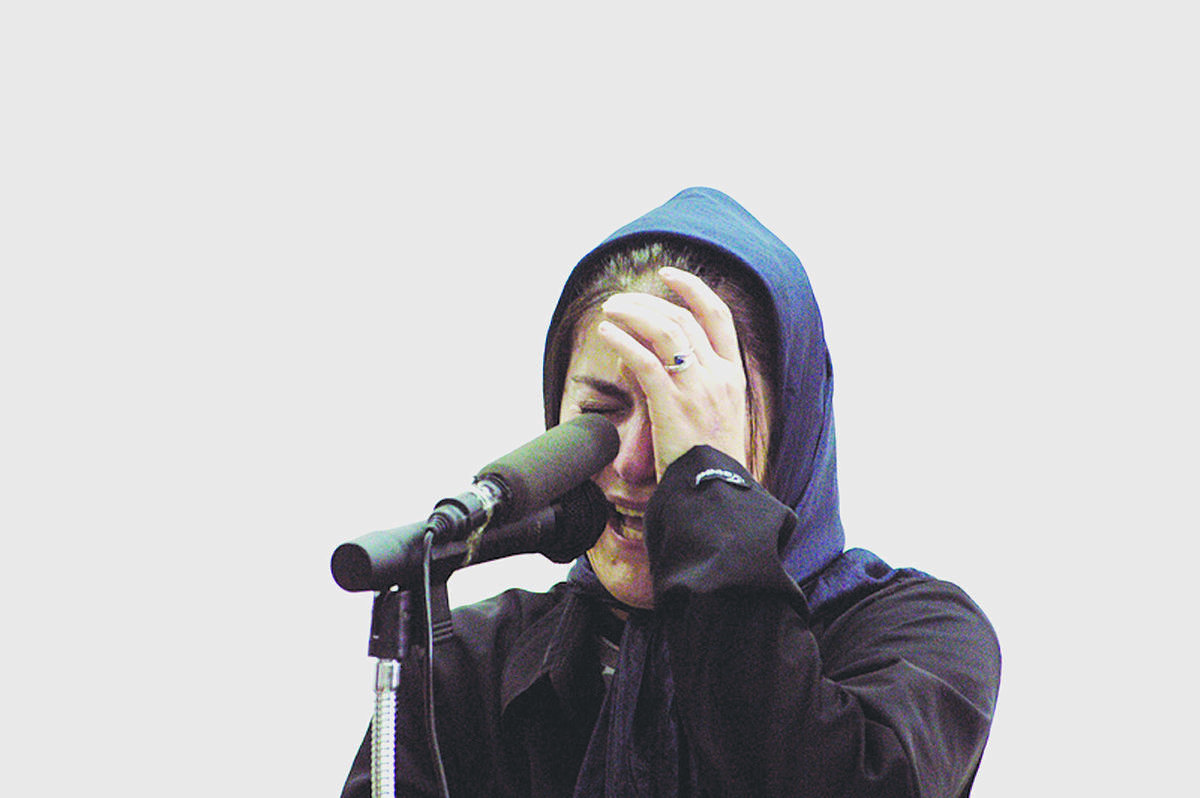

As a woman in Iran, Shahla has less legal power than her famous lover, but seeing her in action in the courtroom reveals another story; the very last adjective that comes to mind is weak. She sings poetry, teases the judge and is generally an enormous flirt, playfully adjusting her chador. She wears a yellow scarf that enhances her bright brown eyes — the very eyes that presumably once caught Naser’s attention. In short, she’s in control.

Shahla’s tale has dominated the headlines of Iran’s papers and weekly “family” magazines since the story first broke. Somehow she has involved everyone in her story, from those who casually peruse Tehran’s newspaper stands to those who unabashedly follow the story religiously.

The Red Card, a film in progress by Mehrnaz Afzali, has followed and documented Shahla’s tale for the past year. The work, a pastiche of sorts, consists of scenes from the trial (which began last year), images from national TV, scenes from Naser’s football matches, and Shahla’s personal home videos. These videos are especially fascinating, and nearly give one the impression that she made them only in anticipation of later use in a film or some other retrospective. She follows her lover Naser in the house, talking to him — or interviewing him, oddly announcing the exact date and time of most of the shots. Such a rough home-video approach is compellingly voyeuristic. Incidentally, the famed couple never share a single frame.

In the end, the glories of Mohammadkhani’s national reputation and multitude of football feats quickly fade, and we are left sympathizing with the somehow endearing accused murderer — not your typical hero, even in the noir sense. We remain in the dark as to whether she is in fact responsible for stabbing the victim to death thirty-seven times, and watching The Red Card isn’t much help: the movie ends just as a new inspector in charge of Shahla’s case appears. We see his suit but not his face, and learn that new evidence may eventually help her out of the cell. The last scene is marked by Shahla’s voice on her home video as she prepares her traditional Haft Sin (decorative ritual) for the Persian New Year.

Afzali’s previous films include Without Witness and Zananeh, the former also about a female killer (a heroine named Farangis who slaughtered two Iraqi soldiers with an ax). Perhaps more than anything, Afzali has a winner of a subject; it is hard to go wrong with such compelling characters. As we wonder if Shahla is guilty of first degree murder, we might momentarily note that our bizarre fascination with the case reveals more about us than it does about a love affair gone awry. Either way, we have the privilege of not seeing the execution before the credits roll.

Shala was originally convicted on June 17, 2004, and then again on January 11, 2005. On October 30, the Supreme Court of Justice ordered a re-trial for the accused murderer.

“Work in Progress” is an ongoing series previewing artist projects.