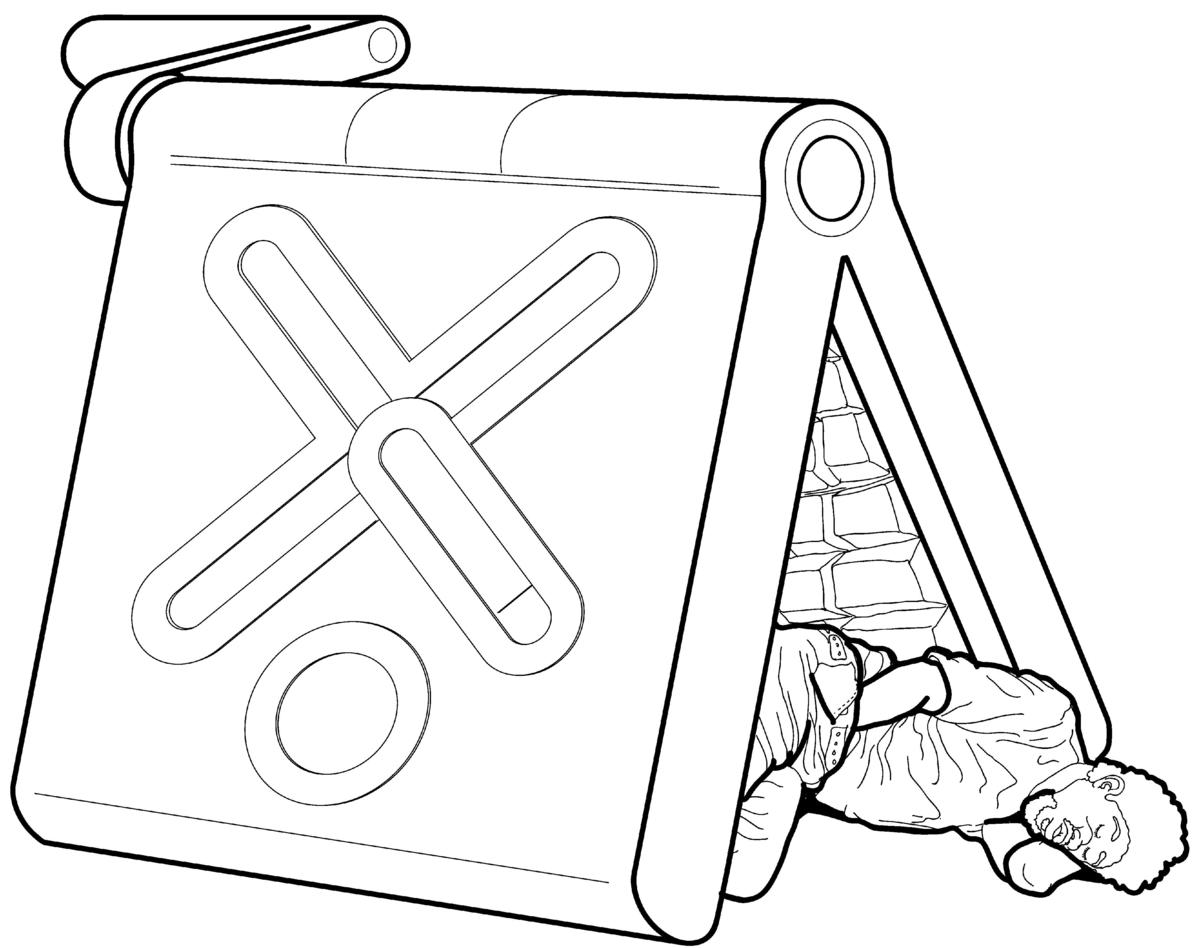

A shiny little green laptop. (It is orange, occasionally.) It has been praised by Kofi Annan as a “breakthrough.” Nigeria’s President Olusegun Obasanjo proclaimed that he was “enchanted” when he came face to face with it. Its biggest supporters, evangelical in their enthusiasm, offer that it stands to revolutionize education in the developing world. (From the very beginning, its designers have insisted that it is an education project — “it is not a laptop project.”) Its detractors, on the other hand, call it a utopian pipe dream, a cookie-cutter concept that is, at best, misguided. It is true that in some circles, it has become fashionable to bash this curious toy-like computer. Either way, few technological innovations of recent years have been the subject of as much hype as the One Laptop per Child project (OLPC for short). Thanks in part to its super-charismatic founder, Nicholas Negroponte (also the founder of the Media Lab at the Massachusetts Institute of Technology), OLPC is ambitious in scale, hardly modest in ambition. Thus far, its organizers have managed to sign agreements with five countries — Argentina, Brazil, Libya, Nigeria, and Thailand — to put these low-cost computers into the hands of millions of students (rumor has it that Negroponte was summoned by Libyan President Muammar elQaddafi to a meeting in a desert tent one evening in August to close the deal). But it has had its share of setbacks, too. India, for example, has rejected the laptop proposal, arguing that the money involved could be better used in tending to the fundamentals of primary and secondary education.

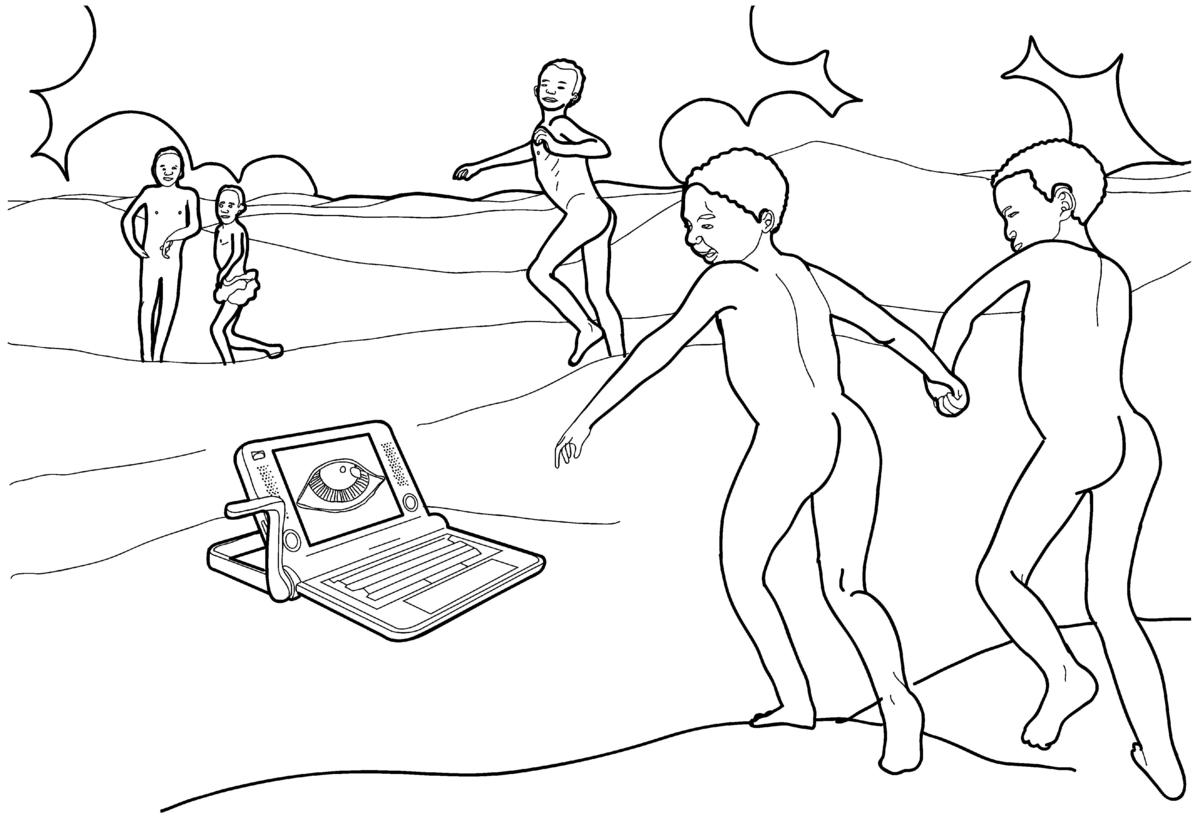

The $100 laptop, as it is often referred to, is spartan. It uses two watts of energy (most regular laptops use between thirty and forty), will be powered by a foot pedal or hand pulley (an initial proposal for a crank has since been thrown out), and will operate with the open-source Linux operating system (an alternative to Windows). The computer will come with a camera, a stripped-down web browser with email, and a simple word processor. The project’s stated goal and ambition is “to provide children around the world with new opportunities to explore, experiment, and express themselves.”

Bidoun, curious as everyone else about these extraordinary little laptops, engaged four persons from different backgrounds and continents to engage in a moderated conversation about the project-to-be. Over the course of a couple of weeks, we could only begin to get some of the most relevant issues out on the table. Here it is, then: a beginning, for there are many more questions to be posed.

PARK DOING:

Hello from Ithaca—

I’m Park Doing, visiting assistant professor in the Science and Technology Studies Department at Cornell and in the Bovay Program in History and Ethics of Engineering. I teach courses in engineering design and ethics, and in the history and philosophy of science. My writings focus on theoretical issues of epistemology in science and the agency of technology.

As I understand it, I am to moderate a discussion (or at least a collection of assertions) with regard to the OLPC project. I am happy to do so. Perhaps you could send me your first round of takes on the project.

Best,

Park

KAUSHIK SUNDER RAJAN:

Hi all,

I’m Kaushik Sunder Rajan, assistant professor of anthropology at the University of California, Irvine. I’ve been studying the political economy of biotechnology and drug development for the past few years. My first project, which looked at genomics and post-genomics drug development marketplaces in the US and India, has been recently published (Biocapital: The Constitution of Postgenomic Life). I am currently researching the outsourcing of clinical trials to India, and capacity and infrastructure building for clinical research there in anticipation of these outsourced trials.

Cheers,

Kaushik

SJ KLEIN:

Greetings from Boston.

I’m SJ Klein, director of content for One Laptop per Child. I have been building and studying creative online communities since 2000, most recently as an active Wikipedian and as a contributor to community projects at the Berkman Center for Internet and Society at Harvard Law School. I’m currently focusing on local collaboration on educational materials in the developing world, something OLPC aims to facilitate.

I look forward to hearing from you all.

Regards,

SJ

ALAA ABD EL FATTAH:

Hey,

Sorry for the delay.

I’m Alaa Abd El Fattah. My life revolves around Free/Open Source Software (FOSS). My day job involves using information and communication technologies for development in the slums and rural communities in Egypt and occasionally participating with groups such as the Association for Progressive Communication and Tactical Technology Collective in other places in Africa.

As a side project, I’ve been deeply involved in the tech side of the democracy movement in Egypt, helping activists use the internet to campaign, organize, and mobilize.

I’m one of those people who think if you give people (especially young [people]) technology, they’ll do amazing things with it. I’m not skeptical about that part of OLPC [but in fact] very excited about it.

However, I have strong doubts about anything that involves governments.

So I’m still confused about the OLPC. The idea is exciting, but I’m not sure it’s the best solution to the problem. In a country like Egypt, where infrastructure problems are not that deep, we can build computers for less than $100 using used components purchased locally.

I’ll make a bold proposal and say that in any slum where there is a reasonable amount of literacy, you’ll find local entrepreneurs assembling computers at the cheapest price possible in that country’s particular economy (I’ve seen it everywhere I’ve traveled). Locals provide a better distribution and support model than OLPC. They lack the ability to affect manufacturer policy and have no software/content component to their work, though. Instead of working on radically different hardware with centralized manufacturing, I’d work on improving the work of the local entrepreneurs.

Cheers,

Alaa

ATANU DEY:

Hello from Mumbai, India.

I’m Atanu Dey, an economist at a technology firm providing mobile value-added services. I’m interested in understanding the factors that underlie economic growth and development. Specifically, I focus on two broad areas: infrastructure, and the use of information and communications technologies in education.

I think the OLPC is a great idea and will benefit a lot of people. Unfortunately, that lot does not include students in poor underdeveloped economies such as India. The OLPC is irrelevant in the context of Indian education. It’s a technological solution, and the problem in India is largely non-technological. It doesn’t make sense to me to recommend an unaffordably expensive technological fix to a non-technical problem. I think that some very clever people have misunderstood the nature of the problem. It is as if someone recommends casting spells to fix a broken car. Psychological methods cannot address mechanical problems.

I hope to explain my position at some length during this conversation.

Cheers,

Atanu

PARK:

OK,

By way of early moderation, let me say that I welcome Atanu’s comment, as it goes to the heart of the matter, but let me also say that I’ll bet that this is precisely the issue that SJ, as director of content for the OLPC project, is taking on and wrestling with and trying to make work somehow. I look forward to hearing his response from the trenches, as it were, about what kinds of linkages are possible or have been forged.

SJ:

Hello again,

I hope that Atanu does write at more length about his ideas. OLPC is an education project, not a technology project, though we are providing tools for learning and collaboration. “Technology” is itself a chameleon word. Alan Kay likes to say technology is anything invented after you were born. In the context of learning, these laptops are toolkits for creativity — and for reading, listening, researching, playing, communicating, working with others, calculating, recording, archiving, and publishing.

If one considers the “non-technological” alternatives: books, tape players, libraries, telephones, chalkboards, calculators, measuring devices, cameras, and printers were each new inventions in their own day. So, too, were materials for writing, drawing, and making music.

I would frame the discussion a different way, starting with a discussion of what is relevant in the context of students in underdeveloped regions and what new tools and learning environments can provide — how they can change the interest of students and teachers in education, their capacity to learn from and teach one another, their ability to study and discover new things, their ability to review what they have learned.

On Alaa’s comments about building cheap computers with local components, I’m not sure that this would scale. What kind of design do you imagine being built for under $100 — would it be robust? And how many could be made? Finding a way to work with local entrepreneur networks is a great idea, but I’m not sure this is the way to produce great hardware. Have you had a chance to use one of the prototypes?

PARK:

Hi Atanu,

Go for it.

What does he mean by “learn” and the “interest” of teachers and students and “discover new things”? It’s so abstract. What does “learn” mean in the institutional context of India, and why would computers for students and teachers have any meaning? Is the ability to work with computers seen as a marketable ability? Does “marketable ability” make any sense? How is technology (inside or outside of quotes) use gendered? Does that matter in an educational context?

ATANU:

Hi all—

SJ, since you asked, here is a little bit of how I see the problem of education in India. India’s primary education is in trouble, which spells trouble higher up the chain. Around ninety-four percent drop out by grade twelve. Only six percent go to college, and of those who graduate college, only about a quarter are employable.

Why is the Indian education system in the pits? Primarily for the same reasons that the Indian economy is in the pits: government control, indeed governmental stranglehold. It is instructive to see that wherever, for whatever reasons, the government has let go of the stranglehold (or was not involved to start off with), that sector has flourished, and how!

For example, consider telecommunications. In five decades of governmental monopoly the telecommunications sector had a base of twenty million users; now that the monopoly is released, we add twenty million users in three months.

Let me reiterate that: THREE MONTHS as opposed to FIFTY YEARS. Sure, technical progress (cellular technology) is a factor. But it is not the major factor.

I could go on for a long while demonstrating why government intervention in the Indian economy explains why the Indian economy performs miserably. This background information is relevant in understanding whether OLPC makes sense in the Indian context.

Indian education suffers from government intervention and lack of resources. Resource constraints are both financial and relate to human capital. Furthermore, the limited resources are leaked away through bureaucratic and political corruption and ineptitude. The major barriers are not technological and therefore a technological solution is not going to alter the situation. Indeed, the OLPC would make the situation worse in the Indian context.

Electronics is neither necessary nor sufficient for education. Merely providing laptops is not going to solve the problem. I will offer that the so-called digital divide is at best a misguided notion and at worst a device used by self-serving money grubbing powerful vested interests to milk the poor for all they are worth.

In the Indian context, the OLPC could in fact widen the “digital divide” and make the system far worse than it is today. The solution to India’s educational problems will use technology intensively, but it will have little to do with children toting laptops around.

ALAA:

About SJ’s question, yes, I’ve had the chance to play with a prototype. And I think the refurbished Pentium IIIs built by local entrepreneurs are much more robust and capable of running a wider range of software.

As for the scale, I’m only making guesses here, but we already have over ten million computer users in the country. Most of [the computers] are locally assembled white boxes. I’m sure if the availability of cheap components is enhanced, our local market can support more than a million PCs for less than $100.

But then this may be very specific to Egypt; I know for sure, based on experience, that you can’t get the same scale in Uganda or Ghana.

My main worry is about the central role of governments in OLPC, and I know OLPC has answers to some of these concerns (by building a machine that looks like a toy, we reduce its black market value, etc). I’m not convinced, though. Our government’s capacity for corruption and stupidity is simply unlimited.

But let’s say that the Egyptian government signs up. That means that anywhere between ten thousand and a hundred thousand students who don’t have access to computers and the internet will have some access (I’m sure most of the million will go to kids who already have broadband, a PlayStation 3, and a couple of PCs at home). Since I’m not paying, I’m not complaining. Ten thousand is good enough for me.

I have no doubt most of the kids will find very good uses for these laptops and will learn a lot from them. But if we expect the laptops to help in achieving conventional educational goals (the stuff supposedly covered by subjects like math, science, language, geography, history, etc), then [it] will require access to content and tools specifically designed for this.

Now, if I’m targeting teenagers who already know how to read and write, then my main problem would be content in local language. But for younger students, you need to worry about more. The laptop doesn’t have to play a role in serving these conventional goals at all (or let’s say the OLPC project doesn’t; other projects that build on top of it can), and it doesn’t have to play a role in solving “problems in the education system” either.

I’ve always felt that intelligent discussion about OLPC is hampered by the ambiguity of the project’s goal and the amount of hype (I suppose hype is essential for fundraising; I’m not blaming OLPC for it).

ATANU:

OK, the problem with OLPC in India:

1. India cannot afford two hundred million laptops at an upfront cost of $40 billion. Merely buying a million for $200 million will be a problem, as you would have to figure out which one of every two hundred students will be the lucky one to have a laptop.

2. One million laptops has an opportunity cost. That is, $200 million could be used to provide one million students with one full year of education plus boarding and lodging in rural India. This money could be spent locally and provide jobs and have the usual economic multiplier effect.

3. Even if we had the $40 billion to spend on OLPC, we would not have solved the real problem of why India has half the illiterates in the world. Government involvement is the problem. And OLPC actually would increase government involvement.

Prediction:

1. The countries that can afford to buy laptops in numbers comparable to their student population will not face the problems of equity and distribution. There aren’t many developing countries like that.

2. OLPC is a costly device for poor countries. It’s going to be a huge waste of money that could be more efficiently spent on other technological solutions such as radio, TV monitors, and DVD players.

KAUSHIK:

I do know a little bit about debates around access to technology in India, though, so here are some broad and sweeping responses to Atanu’s comments. They may not be relevant to OLPC at all, but I bring them in from the context of what I know about the biotech space.

1. Generally, all critiques of technology aside, I think having technology is a good thing. In a country such as India, which has pockets of extreme technological development, it is very important to democratize technological use. One way to do that is to expand access to technology, and one way to do that is through initiatives like OLPC. I don’t really agree with the line that third world countries such as India should be concentrating on more “basic” issues like primary education (the parallel argument in the case of biotech is, why spend so much money on genomics, when that money could be spent instead on public health?).

I don’t see the two as mutually exclusive, and the idea that somehow “cutting edge” stuff like laptops and genomics are best left to the first world, while the third world concentrates on “basics” is deeply allochronistic.

2. I also don’t worry too much about the influence of the state in the Indian context. Of course, having the state involved is a double-edged sword; in India, the state does happen to be the institution best equipped to distribute and/or redistribute access to all potential public goods. The market rarely has the incentive to do so (except in the interests of charity or philanthropy, and those are double-edged swords, too), and at the end of the day, in a basically functioning representative democracy such as India, the state is the institution that is most accountable to the public, however imperfect such accountability might be in practice.

3. My worries and concerns, then, are three-fold. Again, I can’t speak specifically to the OLPC context, but say this in the context of high tech more generally:

Expertise — The intentions of OLPC may be good, but whose expertise gets to count as credible expertise? Is this Negroponte’s expertise? Western institutional expertise? How much is “native” expertise seriously valued and taken into consideration? I’m not saying India shouldn’t learn about technological and infrastructural development from the West — but the way that has happened traditionally has been fairly blind in both directions. On the one hand, Indian actors blindly adopting Western mantras for success without understanding the historical context on the ground in India (for instance, as I have written about in my book, Chandrababu Naidu’s government in Andhra Pradesh enthusiastically aping Silicon Valley through its Genome Valley initiative in Hyderabad, neglecting to take account of the basic fact that the majority of India’s population still lives on and depends on land, and leapfrogging over agricultural development in order to bring about a sort of high-tech that is entirely saturated with Western priorities leaves most of that population out of the picture). On the other hand, various Western “expert” institutions over the last fifty to sixty years telling developing countries what to do based on models that are generated either in abstraction or in the context of advanced liberal societies, unthinkingly exported to the third world at great cost to the people whose lives [are affected]. (I’m thinking here of institutions such as the Kennedy School of Government or the World Bank, [or], more recently, consulting firms like McKinsey and Ernst and Young, all of which are institutions with enormous policy-setting influence in a country like India, but which also oftentimes have provided or tended to provide decontextualized expertise.) Where does the expertise in OLPC come from? Is it expertise from afar, or are more local forms of expertise seriously recruited and listened to? I don’t know the answer to this (and others on this forum will), but it’s a question I crucially want to pose.

“Analog infrastructure” — one of the problems that often exists in India (and not just in India) is that technological infrastructure is often the easiest to set up and get running. What tends to be lacking is what Torin Monahan would call the “analog infrastructure” — the more mundane stuff around the technology that’s necessary to get it functioning. Monahan indeed has a wonderful analysis of “analog divides” in the Los Angeles public school system in his recent book. Getting the computers into the public school system is the least of the problems; there are many other infrastructural issues that prevent the computers from actually bridging digital divides, and those are often the things planners don’t look at. I don’t know what analog infrastructural issues would be pertinent in the context of OLPC, but one I could imagine, which Atanu has hinted at, is local language computing. Unless standardized developments in vernacular computing happen, a basic structural divide that is at the heart of many Indian inequalities — the fact that those who speak English have far greater opportunity to prosper than those who do not — will only get perpetuated. Again, I don’t know how much attention is given to local language computing in OLPC — perhaps lots — but I do know from the work of people like Ken Keniston and Richa Kumar that the absence of good vernacular computing has over the past decade been a serious barrier to overcoming digital divides in India.

Institution building — In India, good things often happen with individual entrepreneurial zeal combined with political will on the part of the state; but almost all of these things tend to get driven by the vision and energy of particular individuals, and traditionally institutional structures that can transcend individual zeal have been much harder to build. OLPC as a singular initiative is all very well — but how is it being located within larger structures that actually contribute to institutional development that can address issues of technology access that go beyond singular initiatives? Again, not something I know answers to in this specific case, but a question I’d like to have on the table.

ALAA:

Regarding the influence of the state: since I’m one of the people who raise the “government is baaaaad” point, I’d like to clarify here.

Even a corrupt government like [Egypt’s] is still the best vehicle to roll out such a project in a short span of time. The problem I see in OLPC is the fact that the project is designed to work exclusively with governments making purchases in the millions. While there are many good arguments for this (all relating to economies of scale), by making government the only possible player, you totally screw things up.

Without involving other players (some market, some nonprofits, some private schools directly) you’ll end up with scenarios like:

1. The laptops are left to rot in a big warehouse.

2. The laptops are sold in the black market.

3. The laptops are distributed slowly through a process of favoritism (to district, school, and even student).

4. The laptops are distributed to schools but not to students, used as classroom equipment that the kids use for thirty minutes per week only.

5. One teacher is assigned the financial responsibility for all the laptops in school, any damage or support costs are deducted from that teacher’s wage, the laptops are on paper priced at $400, so the laptops become a threat to that teacher’s life, and anyone who touches them is trying to put her in jail (this is actually how current school computer labs are managed in Egypt — lovely, eh?).

6. The laptops don’t get any decently Arabized software, so the government assigns a company owned by someone who is married to someone else to develop “educational” software for it, and they develop a broken and/or uninspired product.

7. The government sells the laptops under a scheme that supposedly makes them even cheaper but in practice costs everyone $400 per laptop (they’ve started a “PC for every household” project, whereby people pay by installments; it’s being advertised in all possible channels and the purchase and payment are done through post offices; the PCs cost four times their market value and only a couple of companies are allowed in the project; a large portion of the money goes to Microsoft, and there the PCs come with no support at all; the market is actually able to deliver better but can’t compete with the government’s ability to advertise).

Regarding vernacular computing: localization is key here, I agree, and since the laptop is a queer machine, not like anything else in the market, it requires special software, and someone has to sit down and write this special software. I’d like to hear more about OLPC’s plans for the software. I know they’ve tried to build an international community of software developers to work on the project (that’s why we got a prototype in Egypt), but still I’d like to hear about long-term plans. Regarding institution building: actually, to me what makes OLPC interesting is the fact that it doesn’t need much institutional support once the laptops are delivered to the children. The philosophy is that the kids will know what to do with their laptops (and when they say learning I think they mean the self-exploration and self-expression type of learning). I’ve a lot of faith in this particular idea, but it does require some well-designed software and a large selection of toys and games and stuff; and it does require local expertise that is able to support the laptop informally (which I’m sure will arise with time).