Despite its principal association with repressive regimes, censorship is a recurrent topic of debate within cultural spheres worldwide. In Europe, in particular, the debate has recently entered more treacherous terrain. Religion, or rather, what has been interpreted as blasphemy and religious mockery, has now become the cause of most public complaints against the arts, having rapidly overtaken sex and violence to assume the number one spot. Jerry Springer: The Opera, for example, became a recent cause célèbre: before the musical was aired on the United Kingdom’s BBC Television — adapted from the original production, which debuted at London’s Battersea Arts Centre — word spread that the show included an overweight black Jesus, dressed as a baby, along with tap-dancing Ku Klux Klan members.

By the time TV airing came round, the BBC had received over 55,000 complaints, and its offices were being picketed by protestors. In this case, the BBC stuck with its decision to air the production, citing it as an example of work that had a right to be challenging in its intentions. But would they have been so bold if the production had mocked Allah, or the Qur’an? Highly politicized sensitivities, and the prevalent “fear factor” when it comes to Muslim communities, have contributed to a spate of self-censorship by European arts institutions.

Hotly debated incidences at Tate Britain and the Deutsche Oper come to mind. A display of work by John Latham at Tate Britain in September 2005 originally included God Is Great, an installation consisting of a large sheet of thick glass with copies of the Qur’an, the Talmud, and the Bible apparently embedded within it. Produced ten years prior to the 2005 show, the work is part of Tate’s permanent collection. At the last moment, it was removed from Latham’s exhibition due to concerns around political and religious sensitivities following the July 7, 2005, terrorist attacks on the London transport system. Latham was evidently upset by the decision to veto his work, citing that the work’s premise was that all religious teachings come from the same source, and insisted that a label be included in the show, explaining why the work wasn’t on display. The artist subsequently demanded that the work be returned to him from the Tate’s collection. The gallery, meanwhile, responded by defending its decision, expressing fears that the work would somehow be misrepresented and be given a political dimension that the artist had never intended.

A year later, Deutsche Oper came under critical fire for its decision to pull its scheduled run of Hans Neuenfels’s production of Idomeneo. The contemporary interpretation of the Mozart opera included an additional scene in which King Idomeneo presents the severed heads of the Greek God Poseidon, Jesus, Mohammed, and Buddha. Again, the opera was cancelled due to its apparent potential to cause offense to Muslims. Not that there had actually been any public complaints: the cancellation was triggered by a frightened opera-goer, who phoned the police after seeing it, fearing that it would trigger an extreme response from the Islamic community. This led to a furious debate in the German media over the right to freedom of expression in creative practice, with even German Chancellor Angela Merkel weighing in, commenting on the dangers of self-censorship borne of the fear of political incorrectness.

What is interesting, and of concern, about both Tate and Deutsche Oper examples is that their self-censoring actions were purely preemptive. In both cases, not a single person of Muslim faith had complained, yet commentators on the political right saw fit to describe the cancellations as “giving in to the terrorists.” The presentations were censored purely out of fear of the possibility of attracting the attention of those they might consider to be religious ideologues and grievance-mongers. As it happens, Muslim groups also raised their voices in criticism of the effects of these self-censoring moves. Regarding the removal of the Latham work at Tate Britain, for example, the Muslim Council of Great Britain commented that “sometimes presumptions are incorrectly made about what is acceptable to Muslims, and this is counterproductive.”

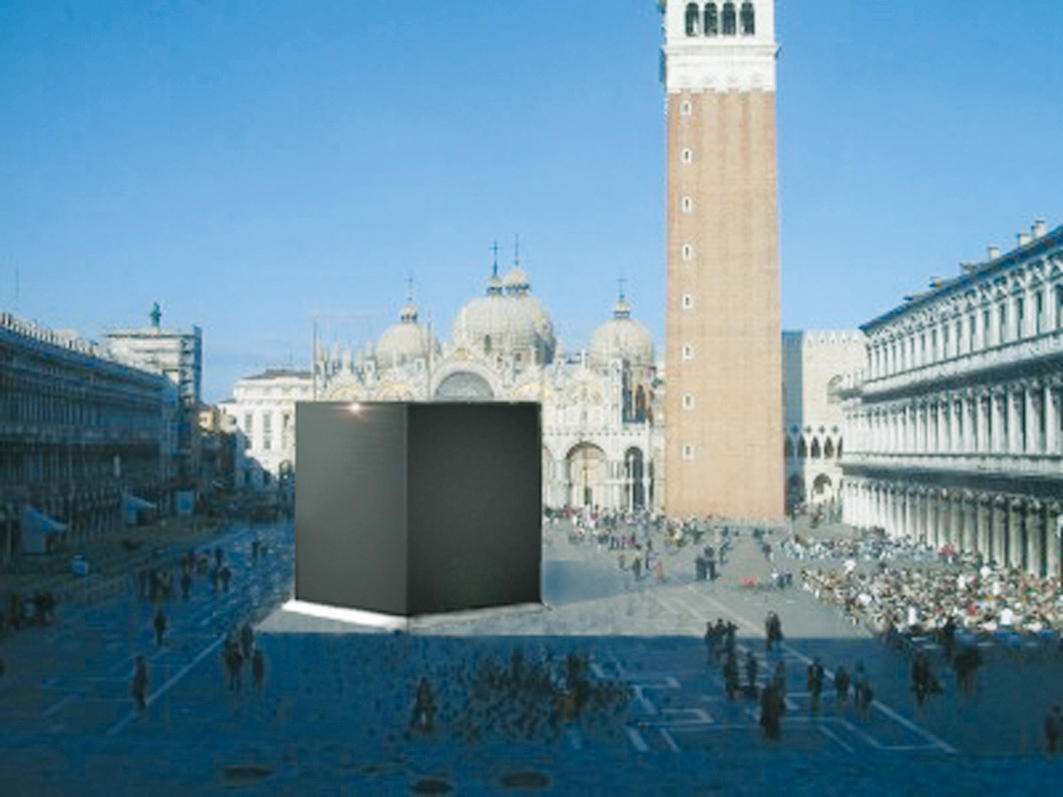

The idea that public institutions have somehow to maintain political neutrality is, of course, a fallacy. Museums, galleries, and other cultural institutions in Europe by necessity, and in keeping with their public funding, engage with the neoliberal agenda. Yet their very contemporary intentions to connect with artists’ political and social concerns often sits at odds with this. Could it be that institutions are not only preempting a critical response from Muslims, but are also preempting possible censorship from a higher authority? There have been many cases of city authorities censoring, or attempting to censor, works of art — from Mayor Giuliani trying to prevent Chris Ofili’s The Holy Virgin Mary from being presented at the Brooklyn Museum, to Gregor Schneider’s Venice Cube (a 50-meter-high black monument shaped like the Ka’aba — being banned from San Marco square and the 51st Venice Biennale by the Venetian authorities, due to fears that it could turn the city into a target for terrorists. Have these high-profile acts of censorship by political leaders caused institutions to be more cautious with their presentations? It would seem so.

Occupying a contested space between political authorities and the public, museums and galleries can find themselves in a tough position — but perhaps it’s time that they themselves took on the role of debating the inadvertent effects of preemptive self-censorship on culture and society. After all, isn’t it the role of the arts to stimulate open debate, to create a space beyond the neat confines of realpolitik? The international media spotlight, vis-à-vis the curbing of freedoms of expression in the cultural sphere, tends to be trained on “the East.” Yet censorship when self-imposed is still censorship, and European institutions are lapped by particularly murky waters. The process by which exhibitions are “adjusted” and operas cancelled exposes the dominance of hearsay and fear over informed debate. Perhaps even more seriously, it also exposes mainstream cultural institutions’ lack of outreach, and channels for dialogue, when it comes to those stakeholders commonly defined in blanket terms as “the Muslim community.”