Yugoslavs are the real friends of the Arabs… Yugoslavia is a real socialist country and not something else.

— Muammar al-Qaddafi, 1974

White Noise

On September 3, 1989, Libyan President Muammar al-Qaddafi stepped off an airplane at Belgrade’s airport. Dressed in white, the colonel-turned-president nodded to onlookers as ground engineers set about emptying the contents of his plane. His entourage of all-female bodyguards — Amazonian both in scale and beauty — stealthily dispersed, as they tend to. They surveyed the grounds. The following day, the Libyan and dozens of other heads of state were to assemble at the ninth summit meeting of the Non-Aligned Movement, the international organization of over 100 “developing” states, spanning from Cuba to China, that had made a vaguely yet romantically defined “Independence!” — be it from the shackles of imperialism or the influence of any and all superpowers — their war cry and raison d’être.

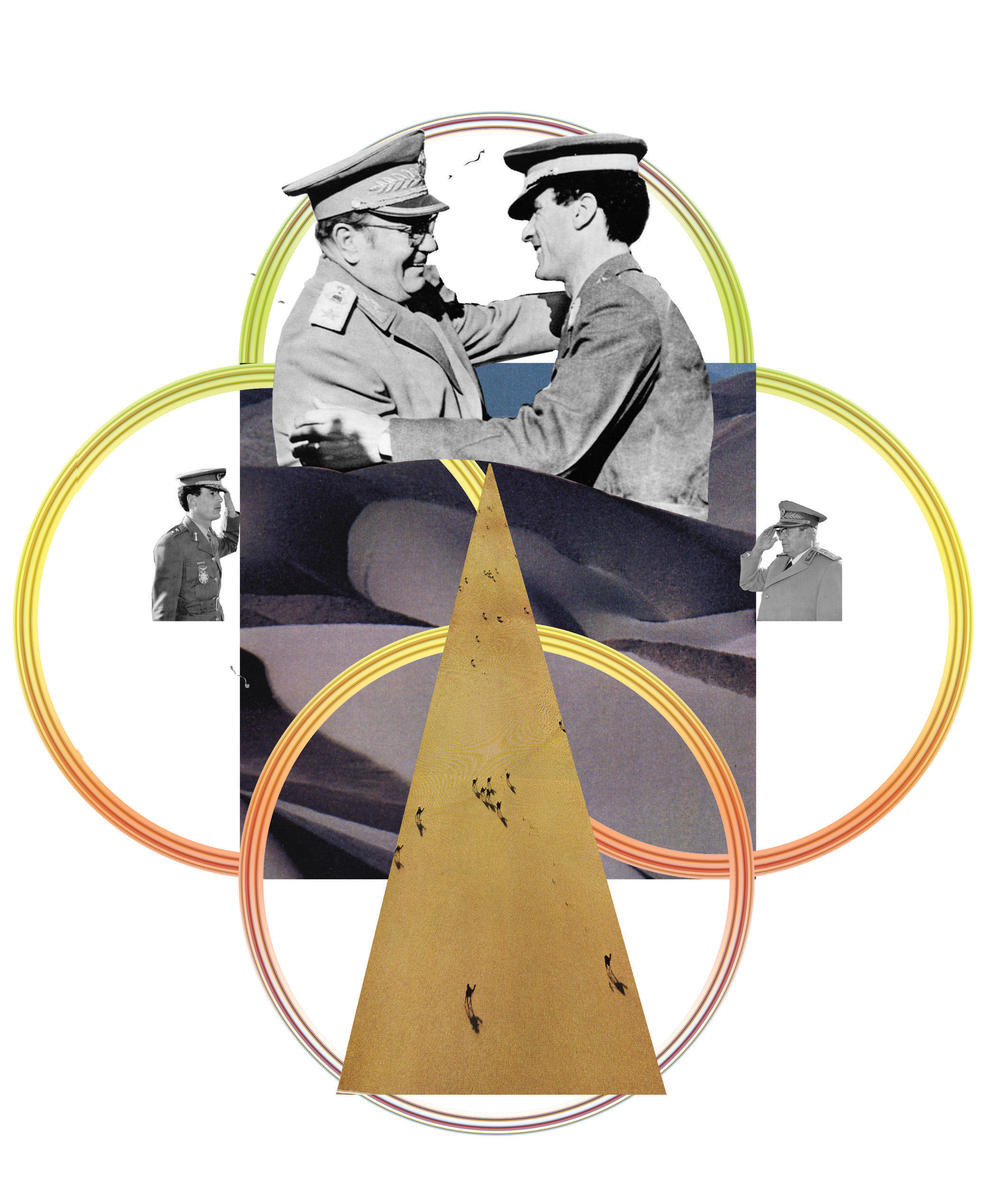

Under former President for Life Josip Broz Tito’s tutelage, Yugoslavia had reached out to Qaddafi, eventually playing a prominent role in the development of the North African state. During the next twenty-eight years, several thousand Yugoslav citizens moved back and forth between the countries, taking part in elaborate infrastructural projects in the desert, from building hospitals to paving roads. The large and complex naval academy in Tripoli, for example, was the work of Yugoslav architects employed by Energoprojekt, a company with multimillion dollar contracts throughout the country. The building was simple, modern, orthogonal, fashioned from prefabricated concrete, and, in true international corporate style, set in an office park. In return for the assistance, Tito received barrels of Libyan oil at bargain prices. It was, you could say, diplomacy by way of barter, and it managed to bring Tito’s Yugoslavia into the world market. Positioned between East and West, a member neither of NATO nor of the Warsaw Pact, the country benefited economically from Tito’s dealings with Libya: it was good news for the economy.

In Qaddafi, Tito (who along with Nehru, Sukarno, Nasser, and Nkrumah was one of the founding fathers of the Non-Aligned Movement) found a partner in shaping his vision of an exciting new geopolitical front. The Libyan, after all, was especially good at positioning himself in relation to master-narratives, be they religious (Pan-Islam), geographic (Pan-African), ethnic (Pan-Arab), or winning-team (I heart Tony Blair) in nature. And so in the 1970s, Qaddafi found an unlikely ally as he fashioned his “Islamic socialism.”

I liked the freedom enjoyed in Yugoslavia and the way in which its peoples respect each other and draw together, although they are of several different nationalities. I also noted with pleasure that the Moslems are free and respected and may practice their religion as they wish. I saw many mosques being built in Yugoslavia. Its millions of Moslems form a very strong element of friendship between Yugoslavia and the Moslem countries, including the Libyan Arab Republic.

But when Qaddafi arrived in Yugoslavia in September 1989, the honeymoon had come to an end. Tito had been dead for nearly a decade. The Yugoslav economy was sputtering. A fractious nationalism was on the rise, and the first calls for self-determination were emanating from Kosovo. A certain Montenegrin named Slobodan Milošević was the new despot in town, and within a decade he would destroy Yugoslavia, not least by destroying the tolerant, multi-denominational framework of Tito’s mid-century creation.

Shuttle Diplomacy

The airplane that brought Qaddafi to Belgrade was full of tribute. It carried one ton of Arabian sand brought from Libya, a massive white tent (de rigeur for the president, who only slept in his own tents), and a small number of camels and horses (Qaddafi was a devotee of camel milk). A selection of gifts for his hosts included traditional Bedouin folk craftwork and pieces of highly geometric, highly modernist Libyan art. Later those mementos were placed in shiny glass cases in one of Tito’s many palaces used as receptacles for gift eclectica.

Habituated as he was to getting his way, Qaddafi asked that he be able to ride atop one of his horses to the 1989 summit’s opening ceremony. Instead — Milošević’s people said no — a compromise was struck. Arriving in a black stretch limousine, he would step onto custom-made Serbian-manufactured faux Persian carpets laid out just for him. His white tent was erected on the grounds of the obliquely named Libyan People’s Bureau, just a few hundred yards from Tito’s former home. Ordinary people who drove by every morning still recall the sight of a cordoned-off miniature zoo of camels and horses that was set up beside the president’s white tent. Camels were milked on the lawn every morning. At conference end, Qaddafi donated them to the Belgrade Zoo, where at least a couple of them remain to this day. They are tokens of that time.

Turbo Boost

It is fittingly (and fleetingly) ironic that today, twenty years after the collapse of the Berlin Wall and at a time when the Non-Aligned Movement has all but lost what cachet it once had, the two former allies — each one reborn in a new historical moment — are once again becoming fast friends. Qaddafi, after all, had famously shaken hands with the Western devil, his theatrical contrarianism all but shoved under the proverbial faux-Persian rug as he embraced reform, dismantled his weapons of mass destruction, and started playing golf with the likes of John Negroponte. In 2006, the US State Department announced that it would restore full diplomatic relations with Qaddafi, the onetime godfather of terrorism. Serbia, meanwhile, was now one straggling piece of what had once been a gloriously unified Yugoslav nation. The country was a shadow of its former self, trying to regain a foothold — economically, politically, culturally — in a new Europe.

And so, in January 2005, when a delegation of politicians from Serbia boarded a state-sponsored flight to Tripoli, it seemed that change was in the air. Within its ranks were politicians and businessmen, including Boris Tadić, the president of Serbia himself. (It should also be noted that within the entourage were one dozen female singers — traditional, neo-folk, and what they call turbo-folk, in style, temperament, dress.)

The long-dormant friendship had rekindled. Energoprojekt would prove to be one of the primary beneficiaries of this rekindling, winning the rights to construct Libya’s new thousand-mile-long railway system. Contracts for thermoelectric systems, harbors, and arms were also signed. Even without the ideological umbrella of non-alignment to grease and propel exchange, it was back to business as usual. Business, after all, is the original non-aligned movement.