London

Alejandro Jodorowsky’s Dune: An exhibition of a film that never was

The Drawing Room

September 17–October 25, 2009

Published in 1965, Frank Herbert’s Dune is the bestselling sci-fi novel of all time. Set twenty thousand years into the future, the plot is both expansive and involuted, concerning — among many, many other things — the aristocratic house of Atreides and the fight for the desert planet of Arrakis’s precious commodity “melange,” produced (why not?) by mile-long sandworms. The Wikipedia summary of the book is practically a novella itself, and Herbert wrote five sequels to Dune; this should place it alongside Ulysses and Naked Lunch as one of the great unfilmable novels.

Unfortunately, films have been made of all three. David Lynch’s fraught production of Dune made it to cinemas, with substantial cuts, in 1984. Though Herbert was generally supportive of the film, Lynch later disowned it. Indeed, in a 1996 essay on the director, David Foster Wallace argued that studio meddling was enough to push the director away from the Hollywood mainstream for good.

Between the best-selling novel and the rather less successful movie lay a film by Alejandro Jodorowsky — unfinished, yet rivaling both in infamy. Due to funding limitations, shooting on the Chilean polymath’s 1976 version never began, but a voluminous archive from two years of preproduction remains — a two million dollar vision of the vast worlds involved. Perhaps the only viable approach to adapting such a wacked-out epic would be to create something inspired by it. In this sense, Jodorowsky was a canny candidate for the task, a guy who knew a thing or two about shifting intentions: with El Topo (The Mole, 1970), the joke goes that he started out making a Western and ended up making an Eastern. Rather than an adaptation, his Dune was to be a reinterpretation: “I did not want to respect the novel, I wanted to recreate it. For me, Dune did not belong to Herbert, as Don Quixote did not belong to Cervantes.”

Rather than rely on the then-nascent special effects industry, Jodorowsky assembled a crack team of visionaries whom he referred to as his “Samurai”: French comics artist Jean Giraud (aka Moebius); Swiss surrealist HR Giger, whose Dune designs were eventually incorporated into Ridley Scott’s 1979 Alien; and British illustrator Chris Foss (who, intriguingly, also illustrated the original edition of The Joy of Sex in 1972).

Moebius made some three thousand drawings for storyboards (later reworked into the successful French comic series L’Incal), on which Giger based his initial designs. The latter was introduced to Jodorowsky by Salvador Dalí, who had been slated to play the insane emperor until he demanded an hourly fee of $100,000, not to mention a golden throne — made from dolphins — that functioned as a toilet. Jodorowsky could only secure funding for an hour and a half of filming with Dalí, so he cut his script to a couple of pages and devised an ingenious, robotic plastic stand-in for the rest of the film. The legend of Dune is littered with many of these what-could-have-beens, loose ends often more interesting than Herbert’s best efforts.

Curated by Tom Morton, Alejandro Jodorowsky’s Dune was a split proposition that mixed prints of the original storyboard designs with works by Morton’s own samurai — Steve Claydon, Matthew Day Jackson, and Vidya Gastaldon — who had been asked to respond to the unmade Dune film as a morphing myth.

The potential problem in this approach was twofold. On the one hand, a survey of the Jodorowsky-commissioned preparatory material, all two million dollars of it, could fill several museums — how to condense it in the Drawing Room’s modest space? On the other hand, how to adequately respond to a vision whose vaulting ambition bordered on hubris and led to bankruptcy? As the subtitle of the show — which is touring to Plymouth Arts Centre in the spring — suggested, it took a light approach to sub rosa influences, alternate versions, and parallel universes. It was both a worthwhile exercise in cosmological thinking and a glance at the possibilities of adaptation.

Presumably due to funding limitations, Morton opted for prints rather than originals. Although familiar from Alien, the Gigers looked decidedly weird — crepuscular but also gelatinous, larvae-like but carious, in ashen greens and stormy grays. The three Giger prints included sketched out details of two leviathan war machines and the Harkonnen Palace. The Foss prints were spectacular (the originals were montages of line drawings with ink, acrylic, and paint on board), clean renderings of planets and spacecraft that suggested CGI renderings, unlike Giger’s more impressionistic versions (the bulbous taupe windows of Foss’s Spice Container had the luminescence of Pixar’s Wall-E).

In this context, it was hard not to make far-flung comparisons: the yellow piazzas, though set against chemically lambent skies, seemed to nod to those of De Chirico. On a depthless background, the Harkonnen Flagship could almost be taken for a red version of one of the Bechers’ water towers. Maybe the latter comparison wasn’t so far off — fabricating the workings of industries in the distant future versus documenting dead industries in the already-distant past.

In the bottom margin of each of Foss’s five immaculate prints was a rough pencil sketch of the surrounding landscape. Although mapping universes and interlocking worlds, Jodorowsky’s Dune was strictly a bottom-up project; in the designs for his film, nothing took a wider view than a single planet, completely characteristic of his modular approach to the project — he had planned for several 1970s behemoths (Pink Floyd, Mike Oldfield, Cluster) to orchestrate a soundtrack for each world. Funding aside, Jodorowsky was ultimately sunk by the impossibility of forcing all of these details to cohere.

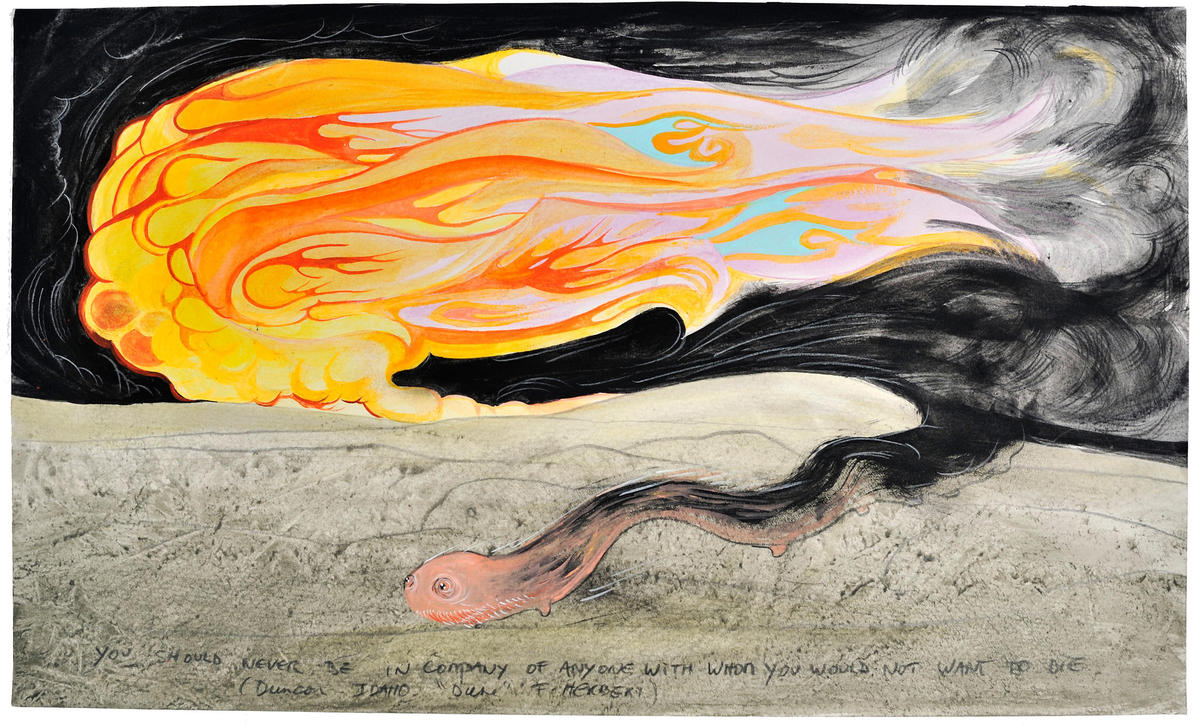

Where to begin was the question facing the latter-day samurai — a question answered unsatisfactorily by Gastaldon’s Blakean illuminated drawings of fiery bursts, molten swirls, and bulbous creatures, which took Herbert’s Dune as a source of inspiration à la the I-Ching. Capitalized pencil quotations were picked at random from the novel, as though chance operations could make sense of the vast opus (if you hadn’t read the book, it was here that you sensed how bad it is). Gastaldon’s works on paper were overshadowed by the original preparatory material.

The work made by Claydon and Day Jackson for the exhibition wasn’t so different from anything else they’ve produced recently, though their sharply mixed registers — modernity and classicism, museological display and gilded Gothicism — made for a good fit with Morton’s brief. On musty, museum-style Hessian plinths, Claydon presented rusted brackets and a khaki-green lacquered bamboo stem, fitted with a brass mouthpiece so as to look like a bong (or cosmic oboe). This was stoner territory, characterized by seemingly fuzzy connections: a brass bust (of Nietzsche?) was fitted with a yellow headpiece (the artist’s t-shirt). Day Jackson’s black-skulled, gold-plated plastic skeleton (To infinity… , 2009) perhaps referred to the planned Dalí double. But maybe it didn’t — this work didn’t encourage much pinning down.

Many are the problems of contemporary mythmaking. In the New Yorker’s recent profile of James Cameron, George Lucas was quoted as saying, “Creating a universe is daunting… . It’s a lot of work.” As Morton noted in his catalog essay, Jodorowsky’s vision of the future of filmmaking would never take place — his favored draftsmanship and labor-intensive planning was taken over by effects-laden blockbusters such as Star Wars, released a year after the Dune project folded. Jodorowsky himself, perhaps presaging David Lynch’s frustrations, put it this way: “Almost all the battles were won, but the war was lost. The project was sabotaged in Hollywood.”