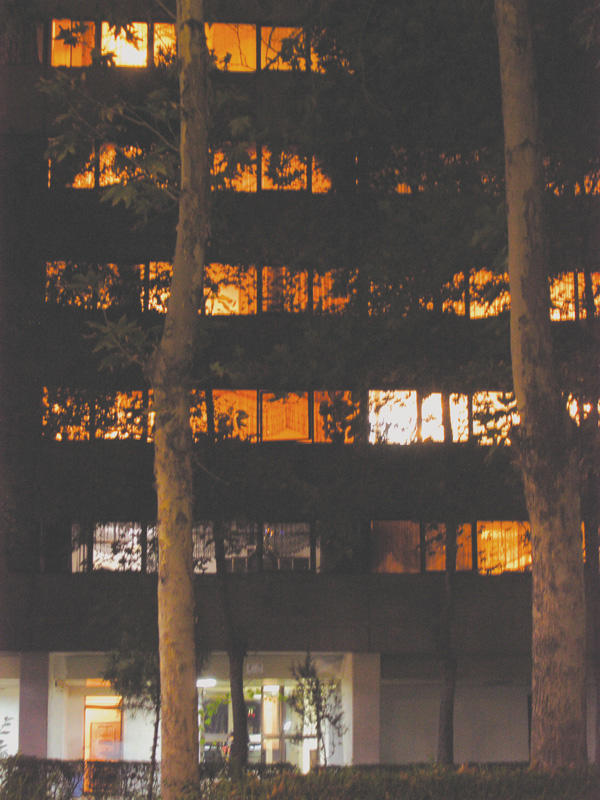

Built during the late 1970s as part of the Shah’s push toward western-style modernization, Ekbatan is a massive community, one of the largest of its kind in the Middle East, sprawling through the center of Tehran. The complex of housing, shops, services and park-like interstitial space cuts an imposing five hundred-acre swath across the westernmost expanse of the city center. It comprises a group of buildings that take the same basic template and stack them into towering and stepped configurations, with relentlessly repeated ribbons of concrete and glass wrapping each building in the 15,500 unit super-complex. Ekbatan was intended to bring a new standard of living, but was never celebrated; just before the buildings were completed, the Islamic Revolution started and brought with it a prescribed nostalgia for the near-rootless “traditions” of “true Islam” and a related opposition to forced modernization imposed from above. And as time passed Ekbatan took on the look — as many extra-large scale modernist housing projects have — of a dystopic prop, a stage for the critique of the contemporary world more than an ideal for living through it.

Yet the conditioned allergy to the totality, anonymity and crushing scale of modernist planning belies an envy of its sweeping vision. Already disillusioned by the inadequacies and failures of postmodern architecture, we harbor an almost illicit satisfaction for the successes of its predecessors. In his essay from 1976 on the Bijimermeer housing project in Amsterdam (a complex that he calls a “socialist Las Vegas”), Rem Koolhaas characterized this phenomenon as “the father threatening the son” in the perpetual Oedipal cycle of architectural discourse.

Still, Ekbatan is often perceived as a perversion of urbanism, a ghettoized scar marked by an isolation that breeds crime and delinquency, although it seems immune to standard attacks leveled at other housing projects. What one finds within is a largely functioning community that appreciates its lifestyle, one not riddled with the social and economic strife associated with the human warehouses of Paris or Chicago. Ekbatan may be traumatic architecturally, but its test-tube urbanism proves to be functional within the context of Tehran. This is a result of its positioning in the city, the completeness of the community and its difference from the other housing projects that are being hastily built to accommodate Tehran’s population explosion.

The divide between north and south Tehran is significant. The north was the focus of the Shah’s attempt at cosmopolification, with tree-lined sprawling boulevards and one eye to the west, while the south is a working class neighborhood characterized by dense and polluted streets. Not surprisingly, there are resentments and tensions between these regions. Ekbatan was placed precisely on the very axis that divides them and is therefore not part of either. In addition to the mediation resulting from this symbolic suspension, Ekbatan collects within its vast complex housing over seventy thousand people, a range of residents with different cultural beliefs and lifestyles, and throws them all together. The towers are certainly striated, housing all the different strata of the Tehran middle class from civil servants to academics to artists to entrepreneurs. Yet Ekbatan itself becomes the unifying factor, even among different ideological camps, defusing prejudice or at least fostering a space where prejudices are less likely to be expressed. Unless, of course, you are not actually from Ekbatan — as a teenage outsider, you could find yourself in a spot of trouble. And even as an adult, you’ll be confronted with defensive, knee-jerk reactions defending Ekbatan to the end.

This sense of community is reinforced by the fact that, to a certain degree, Ekbatan is its own self-sufficient neighborhood, providing the same conveniences that are offered by the city. Parks, malls, gyms, doctors, schools, friends, family-everything can be found right within its imposing bounds. For many, there is not much need or desire to step out into Tehran proper. Some even suggest that the city is a burden on Ekbatan, one young woman going so far as to say that everyone would be better off if the project was in the middle of a beautiful jungle — a far cry from the attitudes toward disastrous housing projects that were and are being constructed at smaller scales but with lower standards and in undesirable neighborhoods.

Of course there are drawbacks of mega-scale modernism, a practice that eradicates difference and culturally-specific accommodations. There are no longer small courtyards for families to gather for tea, and one sees modernist comedies such as coming home to the wrong building because they all look the same and witnessing your neighbors’ most private moments through the floor to ceiling windows. But communities adapt, traditions survive, choices expand and, perhaps in the end, size really doesn’t matter. It’s the way you use it.

Yet the conditioned allergy to the totality, anonymity and crushing scale of modernist planning belies an envy of its sweeping vision. Already disillusioned by the inadequacies and failures of postmodern architecture, we harbor an almost illicit satisfaction for the successes of its predecessors. In his essay from 1976 on the Bijimermeer housing project in Amsterdam (a complex that he calls a “socialist Las Vegas”), Rem Koolhaas characterized this phenomenon as “the father threatening the son” in the perpetual Oedipal cycle of architectural discourse.

Still, Ekbatan is often perceived as a perversion of urbanism, a ghettoized scar marked by an isolation that breeds crime and delinquency, although it seems immune to standard attacks leveled at other housing projects. What one finds within is a largely functioning community that appreciates its lifestyle, one not riddled with the social and economic strife associated with the human warehouses of Paris or Chicago. Ekbatan may be traumatic architecturally, but its test-tube urbanism proves to be functional within the context of Tehran. This is a result of its positioning in the city, the completeness of the community and its difference from the other housing projects that are being hastily built to accommodate Tehran’s population explosion.

The divide between north and south Tehran is significant. The north was the focus of the Shah’s attempt at cosmopolification, with tree-lined sprawling boulevards and one eye to the west, while the south is a working class neighborhood characterized by dense and polluted streets. Not surprisingly, there are resentments and tensions between these regions. Ekbatan was placed precisely on the very axis that divides them and is therefore not part of either. In addition to the mediation resulting from this symbolic suspension, Ekbatan collects within its vast complex housing over seventy thousand people, a range of residents with different cultural beliefs and lifestyles, and throws them all together. The towers are certainly striated, housing all the different strata of the Tehran middle class from civil servants to academics to artists to entrepreneurs. Yet Ekbatan itself becomes the unifying factor, even among different ideological camps, defusing prejudice or at least fostering a space where prejudices are less likely to be expressed. Unless, of course, you are not actually from Ekbatan — as a teenage outsider, you could find yourself in a spot of trouble. And even as an adult, you’ll be confronted with defensive, knee-jerk reactions defending Ekbatan to the end.

This sense of community is reinforced by the fact that, to a certain degree, Ekbatan is its own self-sufficient neighborhood, providing the same conveniences that are offered by the city. Parks, malls, gyms, doctors, schools, friends, family-everything can be found right within its imposing bounds. For many, there is not much need or desire to step out into Tehran proper. Some even suggest that the city is a burden on Ekbatan, one young woman going so far as to say that everyone would be better off if the project was in the middle of a beautiful jungle — a far cry from the attitudes toward disastrous housing projects that were and are being constructed at smaller scales but with lower standards and in undesirable neighborhoods.

Of course there are drawbacks of mega-scale modernism, a practice that eradicates difference and culturally-specific accommodations. There are no longer small courtyards for families to gather for tea, and one sees modernist comedies such as coming home to the wrong building because they all look the same and witnessing your neighbors’ most private moments through the floor to ceiling windows. But communities adapt, traditions survive, choices expand and, perhaps in the end, size really doesn’t matter. It’s the way you use it.