Thankfully, there are enough social spaces with their related practices and rituals in the Arab world today to ridicule prevailing social constructions of the Arab world. Ajram Beach for Women Only is one such space. Ajram, for short, is a private humble beach that caters exclusively to a female clientele, located at the mouth of Beirut’s seaside corniche, in Ayn el-Mreysseh. It is uncanny, certainly unbecoming, to claim that a social realm shaped by antiquated segregation of gender should be hailed as the theater for anything life-affirming. Particularly considering Beirut’s obsessive compulsion to present itself as the seething urban setting with a unique portend to cosmopolitanité (faux) and modernité (faux) and westernité (faux). The moment you push the heavy wooden door leading onto the concrete-clad upper deck of Ajram, and the sea of supine bodies almost entirely naked and brazenly serene unfolds, you find yourself drawing a deep breath of relief. A weight is lifted, a weight you lugged around for so long, surreptitiously, you no longer realized it was there. The nonchalance with which every woman has disrobed, the insouciance in her gait, the care with which she has staged her sabbatical of leisure at the beachfront, are immediately infectious.

I landed in Ajram on a ruthless Beirut summer day, the kind that drives you to the beachfront for salvation, because all other undertakings seem like unwarranted challenges to the natural order. That Sunday I could not join my coterie lounging in one of the private beaches of Beirut’s glamour belt because I had not had time to schedule a grooming séance during the week. To beach without grooming (read waxing) is so deep a breach of social graces, not only would have I had to seek political asylum, but my family would have suffered reverberations for a generation or two after my exile. I suspected the strict society of women would be clement to my appallingly hirsute disposition. And I was right.

Women have many reasons to go to Ajram. Considering the diversity of the clientele, it would be difficult to chart hierarchies in motivations. For some, it is a beach that complies with a proclivity endorsed by observant religious practice. For others, it is a beach where the presence, gaze and authority of men is overcast. And for others, it is a beach where patriarchal values and judgments pertaining to aesthetics of the body and its public display, generally enforced and policed by men, are suspended. Liberté, égalité, fraternité: la république de Ajram.

Contrary to prevailing representations of Beirut, the social space and its population of Ajram is not subsumed in sectarian or confessional cleavages associated — forcibly, more often than not — with almost every sphere of socialization and consumption in the city. In fact, the clientele is very plural in terms of confessional affiliation. It is however, solidly homogeneous in terms of class affiliation. Therein lies the perfidy of sectarianism in post-war Beirut: its discursive power is relentlessly used to permeate and overcast overshadow a lived experience soundly embedded in class structure, such that everyday experiences are tenaciously sorted in an official script that legitimizes sectarian difference and tension, undermining the strong collective commonality within the framework of class.

So I pushed through the heavy wooden door, feigning familiarity, scanning slowly the upper deck and the lower esplanade, looking for a space to settle down, carefully measuring my gaze so it did not linger too long on anyone or any spot and intimidate. My light summer dress flapping in the sun, I dropped my bag on the cement ground. As I unbuttoned slowly, it dawned on me that the magic lay precisely in that moment, when I shed all my civilian accoutrements, dress, shoes and others, and revealed myself almost in the nude, like everyone else around me; then I became a woman just like every other woman, with my hips, my thighs, and my yearning for leisure and abandon. It took only a few minutes, after I adjusted my long chair and initiated the ritual for tanning, for my neighbors to my left — a triptych of women in their mid-forties, reclined in a diagonal angle to maximize exposure to sun rays — to greet me and introduce themselves: Eva, Suzanne and Marie. Their commitment to deep tanning was impressive. They asked questions, more in jest of conviviality than prodding, and babbled on commentary amongst themselves. They slipped me in and out of their conversations with a comfortable familiarity that left me startled momentarily. A seriously swarthy woman in her late forties, seriously swarthy, wearing a t-shirt exhausted from too many rinse cycles, and tied up in a knot around her protuberant belly, walked over and asked if I wanted a parasol, water or anything else from the cafeteria. I looked at her face, carved with wrinkles from a life of physical labor and too long a tenure under the sun. She was smiling, and had called me “honey,” gently. Intimidated by her demeanor and humbled by her means of production, I asked for water and coffee. Eva interjected authoritatively and added a plate of sliced carrots with lemon juice to my request list, “It will make your tan a nice orange brown, you’ll see.” I looked in her direction, she smiled widely, with confidence. I thanked her, smiling.

At the other end of the esplanade, suddenly, there was cheering. A teenager, whose curves had yet to be fully formed was dancing to entertain the group of older women around her. Music was blaring, pop hits (all Arabic) jammed one after the other, screaming into the open horizon. Eventually one of the elder women rose to join her and began to instruct her gently, widening the circles she drew with her hips. It was a lazy Sunday, despite the packed crowd, the music, incessant cellphone conversations all around, children running amuck, and waves crushing on the rocky shore. I found my body unwinding effortlessly, languorous, slowly relishing the rays of the sun roasting my curves. Although fundamentally not ill at ease, only self-conscious of the indictments contained in a gaze, I am never eager to display my body’s girth and gait, my curves and their adipose buttresses. I will spare you this story. Perhaps too familiar to repeat, a B-drama scripted and directed under the dictatorship of the phallo-centric-patriarchal-industrial-military complex. Women flung around me exposed their bodies with a nonchalance I had only witnessed in traditional hammams (public baths). Luscious curves and boyish hips, protruding welt-like breasts and dangling heady bosoms, stretch marks, pregnancy scars, pimples, acne, all was out on exhibit. And not a single gaze vested in judgment.

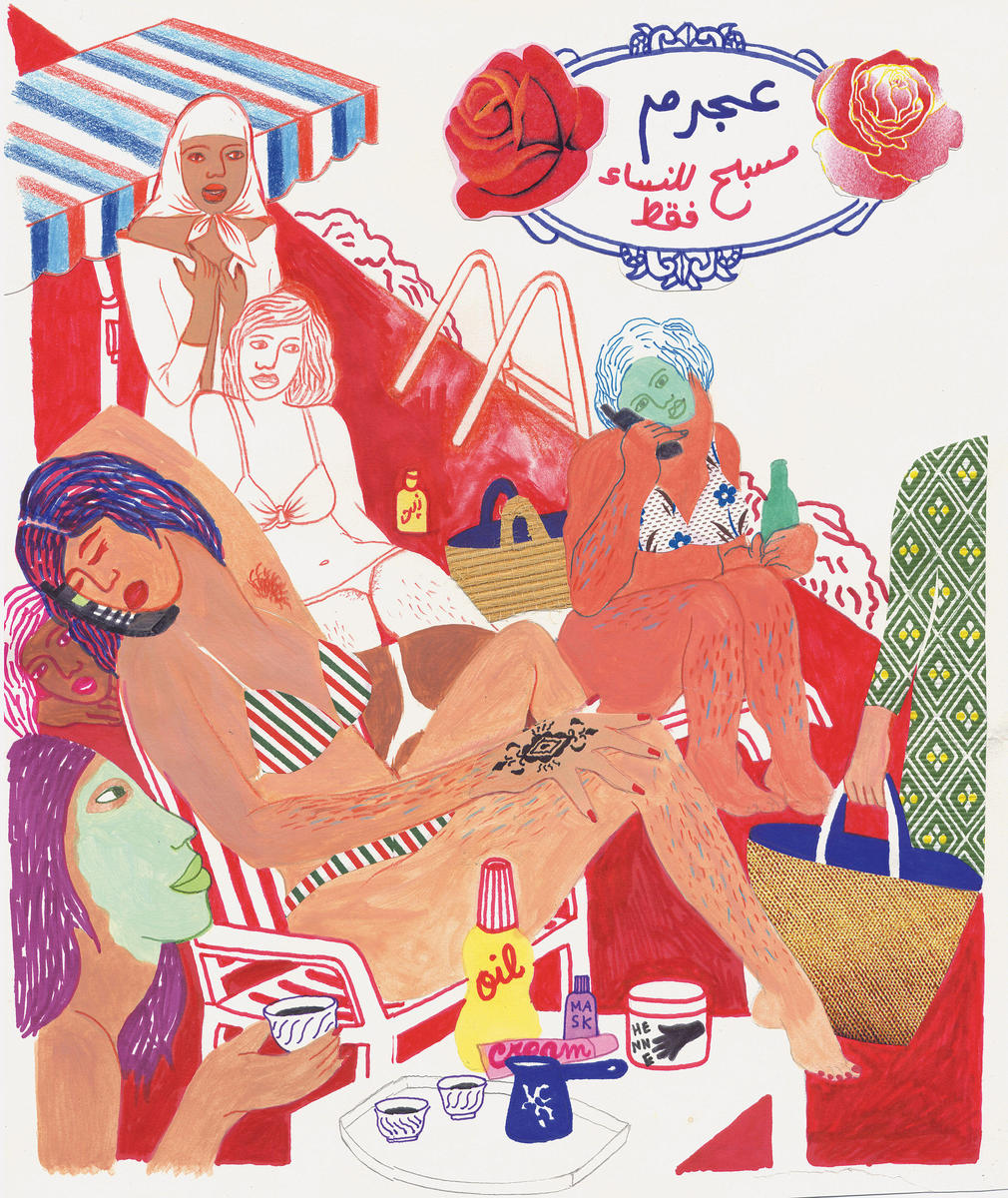

Most women covered their faces in thick brightly colored pastes, their hair tied up in bundles and scarves. “To protect the scalp from burning by sun rays, and severe drying from the sea-salted breeze,” explained Suzanne. My neighbor to the right, Amira, interjected in her turn, to confirm Suzanne’s cautioning. The women around me ordered salads and arguilehs, they drank freshly squeezed fruit juices, they chatted about life, its miracles and its everyday. They changed the positioning of their long chairs following the movement of the sun, they used plastic chairs, pillows and all sorts of paraphernalia to ensure exposure of every nook and cranny in their bodies. They regularly applied products on various body parts in accordance to some wisdom collected in women’s beauty magazines. Ajram was their self-styled “do-it-yourself” spa, their makeshift hammam upgraded to house beautification rituals and frivolous indulgence, in the wide, open-air of the Mediterranean.

Admittedly beaches catering exclusively to women are rooted in a conservative tradition of gender-segregated social practices associated with tenets of observant Muslim practice. They were common in the 1940s and the 1950s in Beirut, but with the loosening of mores and “women’s lib,” they had slowly lapsed by the 1970s. As an urban space for the consumption of leisure, Ajram is perhaps emblematic of the legacy of the civil war, and its microcosmic demographic shifts. But it is equally imbricated in the political mindset guiding the post-war. In the “wild nights” and “days of wine and roses” representations of pre-war Beirut, the neighborhood was identified as an extension of the “hotel district,” in reference to the high incidence of hotels. The reference extends also to activities associated with tourism and urban leisure, namely restaurants, discothèques, beaches, and brothels. During the war, the hotel district became the quasi-permanent theater of violence. Its extension into Ayn el-Mreysseh was less turbulent. While its hotels, restaurants and discothèques shut down, brothels remained operational, even after as its narrow and sinuous streets fell under the political control of Hizbollah. Operational, with a marked shift to a more lowbrow clientele and workforce. Ajram fell in that interstitial space negotiated between the chauvinist conservatism of Hizbollah and the subversive laxity of brothels. Neither the governing regime nor the entrepreneurial class proved able to imagine a vision and a plan for the reconstruction and rehabilitation of the country in the aftermath of the war beyond a flaccid re-enactment of the “days of wine and roses.” The downtown city center, and its branching peripheries like the hotel district in Ayn el-Mreysseh, were resurrected to their former glory, or at least boasted to do so with prohibitive prices and select high-end luxury affect. In post-war Beirut, Ajram maintained its “Women Only” proclivity, but witnessed an upgrade in its clientele to include the petite bourgeoisie. Its proclivity contrasts sharply with the jet-set glamorous identity of neighboring business establishments and is generally endured by the new proprietors of the lustrous hotels and restaurants as an eyesore. Under the guise of contempt for an antiquated segregation of gender, their discomfort is actually grounded in the classical disdain of the ruling class for the petite bourgeoisie.

I was just beginning to doze off, comatose from the heat, when a woman my own age poked me softly, and asked if she could use the empty long chair deserted by Amira, to my right. She was wearing a headscarf, long dress, sleeves tightly buttoned at her wrist, sandals and socks. I smiled and invited her to settle in the spot. She slowly began to unbutton her dress, babbling at me at about how much difficulty she had finding a service (shared taxi), and how hot the day was, and thank God for Ajram, etc… I babbled back at her, introduced Eva, Suzanne and Marie who had perked up and could not contain themselves from joining in. I watched her disrobe, witnessing slowly, how she transformed from a woman whose relationship to her body and notions of chastity were fairly removed from my own, into a woman in a bikini almost identical to my own, eager to take time for herself, darken her tan, simply abandon herself to the warmth of the sun. She, like Eva, Suzanne and Marie, was a real cognoscenti, with a bag full of lotions and potions for different body parts and a whole set of beliefs regarding standards of beauty, delaying signs of aging, and preventing skin cancer.

To many, both locals and foreigners, Ajram is no more than an anachronistic, exotic, kitschy beach, where women in manteau and hijab reveal themselves in skimpy bikinis and thongs: it appears to them as a place for a futile, elusive release from the repressive regime of conservative religiosity muhajjabat (veiled women) endure amongst their own. I, Eva, Suzanne and Marie are systematically excluded from their gaze. Furthermore, in their judgment this gendered makeshift spa of the petite bourgeoisie remains pathetically and tragically captive to the oppressive dominion of phallocentric patriarchy. The male gaze may be temporarily abstracted, but its regime is all-ever-present. While some of these observations contain grains of truth, ultimately, these summary indictments stem from a misunderstanding. Ajram is a social site for release, not for resistance. As such, it is in effect shaped by its clientele, where social convention and prejudice are negotiated and reformulated to suit their inclinations and whims. Nowhere else in Beirut, have I seen obese women, midgets, and women with significant scarring, walk around as comfortably almost in the nude. In fact, Ajram is the unlikely site where a covert solidarity is knit, in generous acceptance of others, an embracing a tolerance of difference, rooted in the shared collective lived experience of class and complicity in deriding and subverting the absolute dictatorship of phallocentric-patriarchal-industrial-military complex. I walked out of my leisurely sabbatical, still hirsute, but empowered in the convivial society and acquaintance of Eva, Suzanne, Marie and Fatmeh. Four more reasons to love Beirut.