Wael Shawky’s most recent video work, The Cave (2005), included in the current Istanbul Biennial, features the artist at the center of the frame speaking without pause for eleven minutes. Shawky advances toward the steadily retreating camera as he recites the Qur’an’s “Surah al Kahf” in one take. The artist’s throat runs bone-dry several times; one watches with empathy as he hastily swallows to preserve continuity. Adding insult to injury, he carries out the exercise while weaving through tight, product-lined aisles in a populous supermarket.

Shawky says it took him more than four hours (and probably many confused shoppers) to nail this feat. This is easy to believe. Having spent time in Cairo with the soft-spoken artist a couple of years ago, I learned that discreet disposition pays no heed to melodrama. Egyptian-born Shawky spent part of his youth in the Gulf before returning to Alexandria, allowing him to witness firsthand the raucous transformation of the region at the hands of astronomic oil wealth and dubious international power plays. He emerged alongside a small group of Egyptian artists including Hassan Khan, Mona Marzouk and Amina Mansour — who employ more decidedly “contemporary” techniques (such as video and multimedia sculpture) than their predecessors. This is no small task when one has the nation’s staid Ministry of Culture arbitrating much of what the world gets to see of new Egyptian art: pretty, patriotic, petering out at modernism.

These notions bring me back to Shawky’s recitation of the “Surat Al-Kahf” — specifically the story of the Seven Sleepers that is claimed by Islam and as well as Christianity. In both traditions, the sleepers flee the encroachment of evil pagans seeking to dash their (respectively) sacred beliefs. They’re subsequently sealed inside a cave where they sleep for two or three hundred years. Eventually they awaken, safe and pious as ever, to invigorate the faith of a new but weary generation through their miraculous existence. What’s crucial to Shawky’s broader agenda is the Rip Van Winkle notion of vacuum-sealing the wisdom of yesterday so as to smash it into today’s mess. In the best case, this yields a terrific rattling of collective convention; more likely it yields an even bigger mess, like it did in Bill and Ted’s Excellent Adventure, or with colonization.

Given the weight of the work’s direct subject matter, one cannot help but react with an initial knee-jerk: is the artist really so literal as to align the many bleary-eyed shoppers in The Cave’s contemporary supermarket with the Seven Sleepers’ depraved masses awaiting salvation? Or is Shawky trying to position the shoppers as sleepers themselves, innocently drifting toward their own cataclysmic destinies, beer and chocolate bar in hand? At the moment the video might be swallowed whole by an Intro to Philosophy class, a completely average teenage boy enters the frame to all but make rabbit ears over Shawky’s head. Thankfully the whole affair is wrested from moral severity by its setting in the neon-drenched bosom of consumerism. This way, the revelation comes by acknowledging that Shawky’s gesture of labored didacticism must bow to the reality of grocery shopping, absurdly quotidian and insurmountably human as it is.

In much the same manner, the video installation The Green Land Circus shines a light on the scuttle of the masses. As shown in 2005 at the Townhouse Gallery’s factory space in downtown Cairo, the work takes the form of a huge two-pole tent, swollen around pre-existing support columns, pushing up against the roof of the exhibition space. Inside the tent inside the gallery, the fabric is painted silver so as to eerily reflect the blue glow of three plasma screens.

Any technological ambiance in the installation is sharply offset by a floor completely covered with earth that the audience traverses on a dilapidated, wood-planked walkway. A mud-brick enclosure on the left of the tent stands partly in ruins to boot. Similar to The Cave’s invocation of ancient scripture, contemporary tactics here remain tethered to dusty aesthetics—a strategy that risks cramming both artworks into the easy (and kitschy) “ethnic” pigeon-hole. But to dismiss Shawky’s work as resting on its nouveau-Mid-East laurels is to overlook its considered commentary on the smudge of civilians at large. For in as much as the artist dramatizes elements of the Arab world, he also dramatizes the body, the reach of capitalism and the art world’s hunger for entertainment.

Take The Green Land Circus’ trio of projections. The main screen, located at the end of the walkway, shows a staged altercation erupting between fifteen people. A second projection to the right of the walkway reveals the casting process for the main video. The third screen to the left features old screen tests of Shawky’s actors. (The most memorable is a 1970s comedy sketch showing conversation between a Middle Eastern Burt Reynolds and a peroxide-headed midget.)

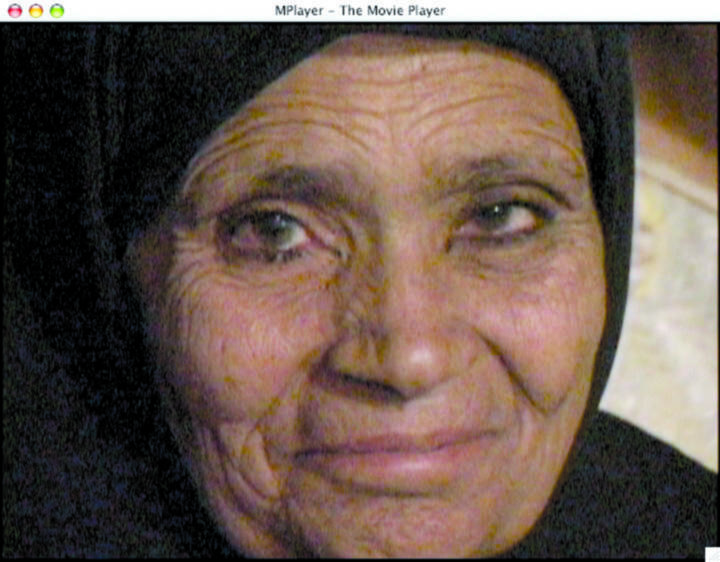

The whole thing stinks. But in a really effective way. Shawky successfully captures humans’ odd physical matter: rotund women caked in makeup staring out at the viewer, tiny people fiercely tussling, close range shots of sullied midsections mushing together. The idea of these characters overcoming their screwball corporeality to convince an audience of a heated fight scenario is ridiculous. Yet while the viewer is privy to this behind-the-scenes view of creating a fiction, they are also in the scenes themselves, standing within the bizarrely man-made meta-environment where the projected images were staged.

One of Shawky’s earlier works, Sidi El Asphalt’s Moulid (2001), also benefits from ramshackle architectural installation. This time the audience is invited into a tar-drenched, cardboard shanty-town. The mini-metropolis is scaled so that the average viewer stands as tall as a five-story building. There is no attempt to conceal either the phoniness or the hand-made quality of the construction, which takes on the odd properties of Mr. Roger’s Land of Make Believe. The tacky black space turns even more sharply toward twisted dreamscape with Shawky’s addition of recessed plasma screens showing the rhythmic hypnosis of a crowd at a Moulid set to Cypress Hill’s (Rock) Superstar. (At least there are no puppets.)

As with much of Shawky’s work, one marvels at the fact that these disparate slabs do fall together —i n this case thanks largely to the deft syncopation of whirling Moulid footage with the beats of a 1990s movie trailer staple. Viewers are even invited to laugh at the sight of an attendee grabbing his crotch like he’s Eminem at the Video Music Awards. For a moment the work seems to address the concept of “globalization-kids” foisted on today’s youth by older folk in awe of the internet. Does Shawky invite homies the world over to build their treehouses, too? I don’t mean to say that Sidi El Asphalt’s Moulid is all construction. But in the end Shawky’s work functions for the widest demographic as a heartfelt monument to creating something out of too many things.