Artist William E Jones has made films about a pornstar (Finished), the Southern Californian Latino fans of Morrissey (Is It Really So Strange?) and the unlikely documentary and/ or narrative moments within sex films (v. o.), among other hypnotic and subtle works. Through vivid photography, film, and video, as well as considered and considerable prose (see his website: www.williamejones.com), Jones brings to attention modes of being and behaving almost on the brink of obsolescence. No small part of his study is the labor involved in the production of the erotic, the various class and sexual inflections of what it means to be “working” (as a favorite working boy’s T-shirt put it, “Porn Stars Work Hard”). Jones carries on a tradition of experimental filmmaking in no small part about and within the noir heart of that intersection of bodies, industry, failure, and desire called Hollywoodland. What follows is an excerpt of our ongoing conversation that weaves around the narrative of porn, the myth of Roman emperor Heliogabalus, the impact of the internet on documentary filmmaking, the whims of the censor, and beyond.

Bruce Hainley: Before we discuss method and processes of research, perhaps it would be good for you to introduce Fred Halsted, the subject of your next biographical project. When and how did you first hear about Halsted and his films?

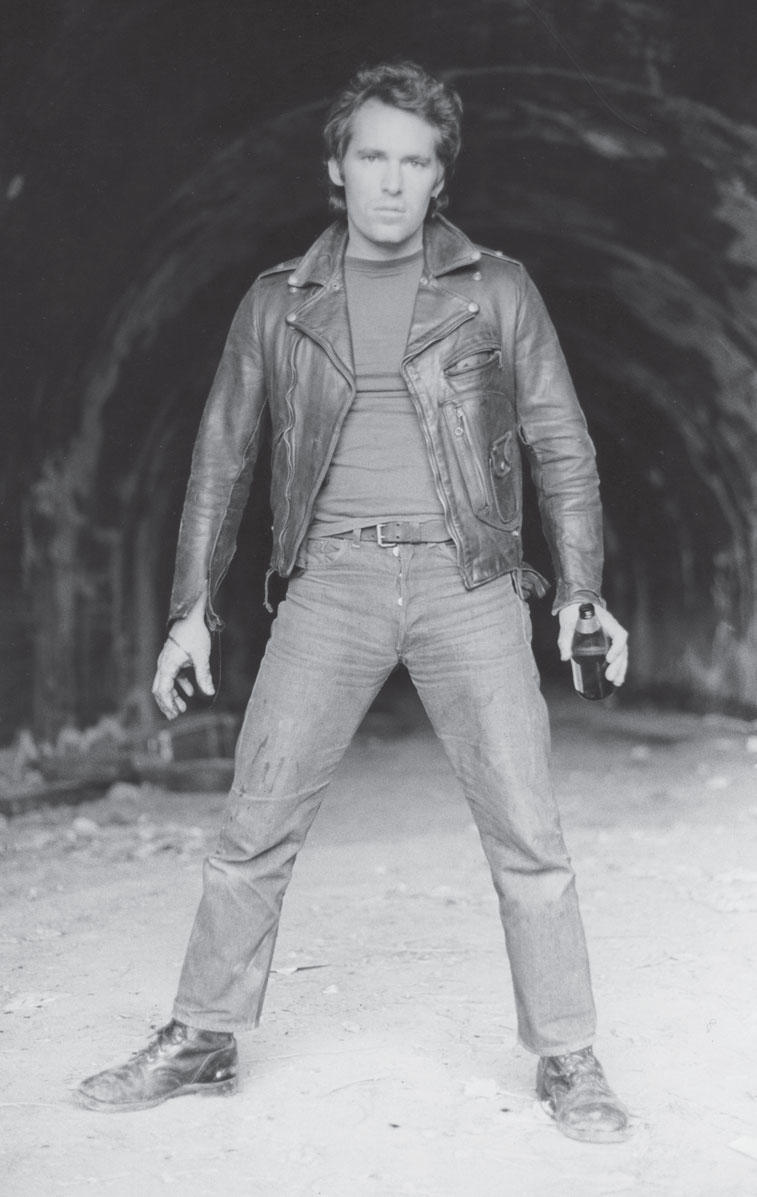

William E Jones: I am tempted to say that I’ve always known about Fred Halsted, though clearly that’s impossible. Halsted’s film LA Plays Itself (1972) captures the brutal irony of the “good life” in Los Angeles, which is a tough town, as any hustler quickly discovers. When I first saw it, I thought it was, aesthetically speaking, the greatest gay porn film.

Fred Halsted invented himself as an artist and as a persona. He was the son of an agricultural worker mother and a construction worker father. He grew up in various places in California and spent nearly his entire adult life in Los Angeles. He studied botany, not filmmaking, and gardened for clients such as Joey Heatherton and Vincent Price. He became a successful businessman with a chain of plant nurseries.

In 1969, the year that all-male sex scenes, or “loops,” were first shown publicly in East Los Angeles, Fred decided to get in on the action. The US Supreme Court had not yet established a legal standard for obscenity, so it was a wide-open field, still too risky to be industrialized on a large scale. Fred devised his debut film as an “autobiographical, homosexual statement” directed by and starring himself. Later that same year, he met the love of his life, Joseph Yale, who appeared in the film’s climax. (Joseph had been led to believe Fred was making a nature film, an assertion that did have an element of truth.) This situation–not the sex scene, but the filming of it — scared Joseph off, and the two didn’t meet again until after LA Plays Itself was released in 1972. Over the next twelve years of their relationship, Fred and Joseph made a number of films together, operated a mail order business, published a magazine called Package, and ran a sex club in Silverlake called Halsted’s. Yale died of AIDS in 1986, and Fred never recovered from the grief. In his final year, Fred wrote an autobiography entitled Why I Did It, the manuscript of which seems to have been lost. Halsted committed suicide in 1989. He died without a will, and his estate is in the hands of a family that has shown no interest in attending to his legacy.

LA Plays Itself has an interesting relation to history. It is an unintentional documentary of the circumstances of its filming, and this “documentary effect” only gets stronger with passing years. In the first half of LA Plays Itself, a scene between two young men in Malibu Canyon gets interrupted by bulldozers advancing on the wilderness that shelters them. It’s ironic that there is still significant wilderness in the canyons that Fred thought would be utterly destroyed; what vanished was the Hollywood street life that Fred extensively filmed and probably thought would last forever. Hustlers no longer ply their trade along Selma Avenue by the YMCA. They now hang out in internet cafes to make their dates online. Various websites have replaced the meat racks, but this virtual space, while safe from the physical aggression of the LAPD, is distinctly unphotogenic.

BH: Your film Finished (1997), your last shot on celluloid, used porn star Alan Lambert as its centrifugal force, the absent center your thinking and your shots of Los Angeles orbited. Lambert also took his own life, and we could talk a lot about our mutual fascination with, um, dead beauties, but perhaps it would be more to the point to ask how the process of research has changed for you over the past ten years.

WJ: Narrative films generally concern the struggles of living protagonists who move from place to place, solve their problems, and end up as part of a romantic couple. In the case of a dead protagonist, the narrative depends upon finding out what sort of character he or she was. The conclusion of such a story comes when the investigator — who is not only a stand-in for the spectator but also a sort of ventriloquist throwing a voice into a dead person — achieves a satisfactory quality of knowledge. This necrophilic strategy entails some risk. The result is an art film. The most famous example in the classic Hollywood cinema is Citizen Kane, which is the beginning of narrative cinema’s great ambition — or great decadence, depending on who’s constructing the pantheon.

During my investigation of Alan Lambert, I discovered very little about his life; I discovered much more about how to make a biographical film. When the people around Alan presented difficulties or entirely refused to cooperate, I was forced to fill the gaps with a testament to my desire, my curiosity, my moral scruples. I was in the position of making an argument for Alan that was really an argument for myself on the slimmest of evidence, and I found the challenge fascinating.

My Fred Halsted project initially provoked some weary skepticism (“Oh, another film about a suicidal porn star…”) but Finished and the new movie, separated by more than a decade, have significant differences. For Finished, shot on film, I could not afford to conduct on-camera interviews, so the movie’s main dialectic posed shots of locations associated with Alan Lambert against found images of him. Switching to digital video has allowed me to introduce on-camera interviews to the compositional elements at my disposal. Since I am not abandoning still images or landscape shots, the interaction of these elements is potentially more complex. Another shift with far-reaching consequences has occurred. Whereas I had to fill the void at the center of Finished with my speculations, I have recently found another preoccupation, at once more concrete and more banal: internet research. Like everyone else, I am astounded by the volume of information, often random and dubious, available to me on the internet. This new level of detail brings with it new frustrations. I now know what color eyes Fred Halsted’s stepfather had and that he had a tattoo on his right forearm, but I have little idea of what he was like as a person. I know exactly where Joseph Yale’s parents are buried, but I haven’t found a single living person who was a close friend.

BH: Where does reading come into this? Your films often have a particular book as methodological inspiration. For Finished, it was AJA Symons’ The Quest for Corvo, whose subtitle reveals its stake in your project: An Experiment in Biography. Symons puzzles together from almost chance encounters, from the texts of Corvo’s that remain (elusive published works, private letters), the subterranean, hand-to-mouth life of an eccentric homosexual littérateur. Some of your recent video works — the kids might call them “mashups” — borrow moves from Raymond Roussel. I wonder if there’s a particular book or author your Halsted project will, in some manner, become a gloss for or homage to? Is this, in part, how you find a form for your desires and materials?

WJ: My work never develops in an efficient, linear fashion. The writer of a narrative film must know how a movie ends at an early stage of its script; to do anything else is to court disaster. I consistently make disasters, not knowing where the research or the writing will lead. In this respect, I have a lot in common with more conventional documentary filmmakers. Where my practice differs is in entertaining the kinds of digressions that most other filmmakers would cut out. For me the digressions are the body of the film.

With the Halsted project as an excuse, I have read many of the historical sources on Heliogabalus. He was a pampered, flamboyant youth who became a Roman emperor through the machinations of his mother and grandmother. As high priest of a Syrian sun god, he attempted to impose his Eastern religion upon Rome, and for his trouble, he was brutally murdered by soldiers in the army that supported his rise to power.

Unless an emperor had something to gain politically from linking himself to the person he succeeded, he generally waged a propaganda war against his predecessor. Heliogabalus was a ludicrously easy target for this sort of posthumous punishment, or damnatio memoriae. Tales of Middle Eastern effeminacy and luxury had furthered Roman political interests for hundreds of years. Many elements of Heliogabalus’s biography — his smothering dinner guests with a shower of rose petals, his masquerading as a palace whore, his offering a reward to whomever could perform a sex change operation on him — are likely exaggerations at the very least. Little is known with certainty about Heliogabalus; on the other hand, the apocryphal literature is extensive.

The chief source of this material is the Historia Augusta, a long text by six authors, including Heliogabalus’s biographer Aelius Lampridius. That connoisseur of perversions Robert Burton and even the towering figure of Edward Gibbon, took the text as authentic, but subsequent scholars have demonstrated that most aspects of the work are fictional or plagiarized, and have gone as far as questioning the very existence of Lampridius. One diligent classicist called Historia Augusta a “farrago of cheap pornography.”

Heliogabalus the mythic figure has inspired many artists and writers, including Antonin Artaud, who expressed a serene indifference to questions of strict historical authenticity: “I have written this Life of Heliogabalus…to help those who read it to unlearn history a little; but all the same to find its thread.” New access to data, and with it, new forms of cheap pornography, admit new possibilities for finding the thread of history.

BH: Part of your pursuit is biographical, and we both have come up against people who will not speak about what they know; people who will tell tales but only anonymously; subjects who are struck with the convenience of amnesia. Have you learned any tricks to woo revelation from the reluctant? And, if not, how do these silences and gaps become structural, paradoxically productive, in terms of changing your thinking as well as, potentially, a film’s form?

WJ: I once worked at the offices of National Geographic, and I read their manual dictating how to make a film. The production of a program always began with images shot at great expense in various far-flung locales. Writers then composed narration to accompany the footage; their job was to tell the audience what it was seeing. With few resources at my disposal, I begin a film with words and collect images to accompany them. The distinction — explaining what is seen vs hearing or writing, then imagining, something to see — is crucial.

In the US images are routinely censored and controlled, but words circulate much more freely. It is very difficult to suppress completely any text with some claim on literary merit. This disparity favors films that may deal with sex but avoid sexually explicit images. The situation abroad is different. Australian censors refused to sanction a screening of my video The Fall of Communism as Seen in Gay Pornography, simply because the title mentioned what they were supposed to be guarding against. This episode was a pointed reminder of the power of a single word.

The dictionary definition of aporia — a passage in speech or writing incorporating or presenting a difficulty or doubt — also describes a generating principle of my work. Sometimes the difficulties come from without; at other times I impose them on myself. This method strikes the conventional as perverse. For Is It Really So Strange? (2004), I couldn’t afford to license a constant stream of songs, and spectators expecting the kind of music documentary that merely advertises the recording industry were disappointed. In some quarters, I’m known as the person who takes the sex out of pornography. I prefer to concentrate on other, clandestine (though paradoxically, more chaste) desires co-present with the obvious ones.

I may be obliged to complete my current project without the use of footage from Fred Halsted’s films. I will have to rely upon interviews with his friends and colleagues, an exceedingly small bunch of survivors, some of whom are reluctant to speak to me. The only promise I can make my subjects (and one that never works on young people) is that anything they offer me has some claim on posterity.

BH: The other night I was trying to explain to someone my investment in a particular history that has been occluded by the first wave of AIDS. He accused me of being reactionary or, worse, nostalgic. (I told him I was deeply interested in what gay youth were up to but that I wasn’t persuaded to believe that they organize their identities around the sexual, embrace the still potential radicalism of that history and culture, or spend much time lost in thought about what it meant to advertise, even publish, one’s non-normative desires.) Would you say something about your work’s involvement or response to that history? Halsted would seem to stand for, even embody, powerful resonances and artesian energies now waning, if not lost.

WJ: The 1970s hold a strong fascination for me, and my chief source of impressions of that time is After Dark. Originally as a dance magazine, then under the general rubric of entertainment, After Dark provided a record of a sensibility. It served as arbiter and instruction manual for those gay men who flocked to New York as the center of the world, and who took high culture seriously even when they didn’t understand it.

From my point of view — and not just in the context of After Dark — the losers or failures are more significant than the stars. There is an inexhaustible wealth of inspiration in the work of a performer who was a bit too extreme for crossover success; in the off-kilter flash in the pan whose precise appeal eludes us today; in the hot spots, icons, and sartorial trends that proved ephemeral.

What interests me is akin to the work of classical scholars piecing together fragments of texts from antiquity. Legal problems, shady business practices, pseudonymous authorship, and a general cultural disdain have prevented us from gaining anything more than a rudimentary understanding of what gay porn is and how it has evolved over time, for example. The situation for “legitimate” gay culture (whatever that is) seems only slightly better. The deaths of so many of the participants have practically transformed researching gay life in the second half of the twentieth century into an archaeological endeavor.

From my research in the archives, I could cite myriad examples of historical sources that deserve our attention. Some of them haven’t even been catalogued or indexed yet. Now to us falls the task of making sense of it all.