Nestled along downtown Cairo’s busy Talat Haarb Street, the Yacoubian building is easy to miss. The apartment building exhibits the area’s standard mixture of residential and commercial, its doorway plastered with signs and its first floor nothing but a row of typical and unremarkable small shops. The entrance itself, flanked by brightly lit displays of men’s shirts, looks like any other store. The building’s austere Art Deco exterior is pockmarked with air conditioning units and billboards, and you must crane your neck sharply to catch a glimpse of the geometric patterns of its iron balcony railings or the dusty band of ceramic mosaics that decorate its top floor.

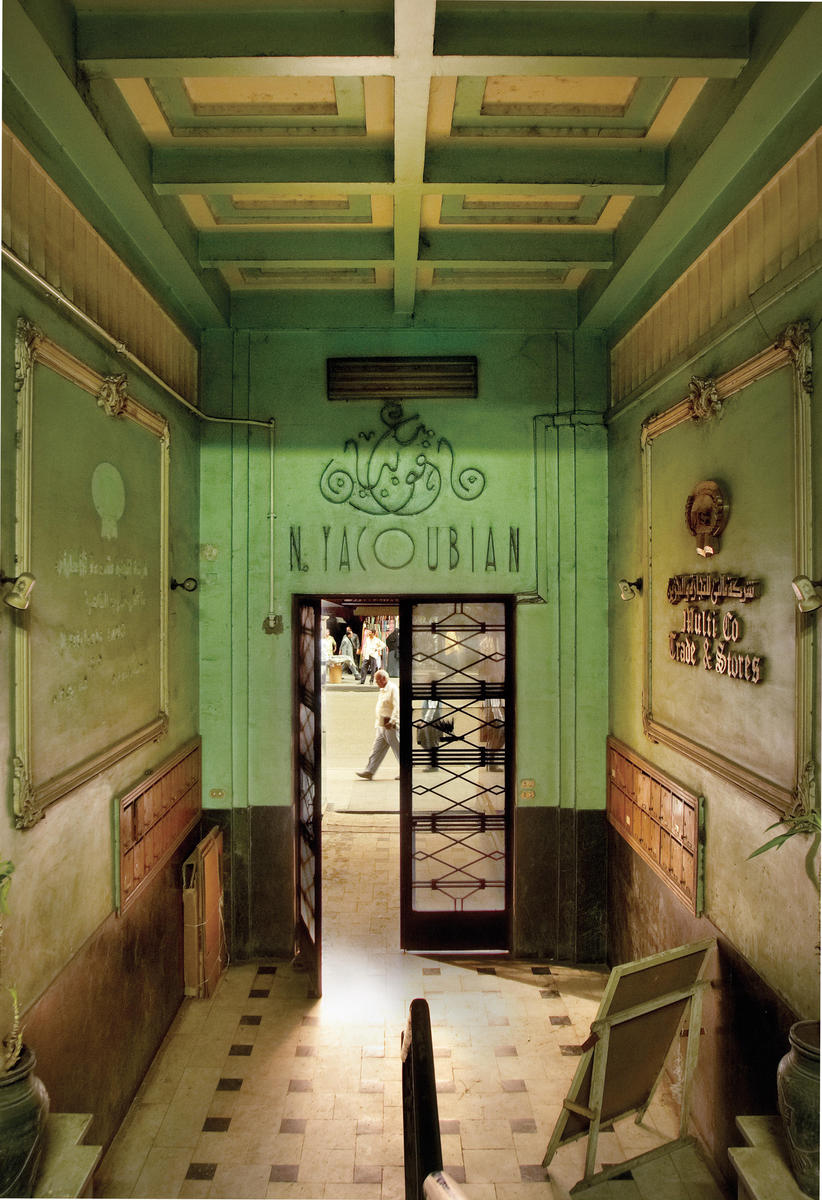

In short, don’t be surprised if descending upon the location that inspired Alaa Al Aswany’s bestselling novel The Yacoubian Building is an anti-climax. Once located, however, the building does yield one moment of clear aesthetic pleasure: Venture inside, turn around, and you will find its name elegantly written in elongated, wafer-thin letters, in Arabic and English, across the inside of the threshold. This was likely a finishing touch of which Nashin Yacoubian, the Egyptian-Armenian businessman who built the building in the 1930s, was particularly proud. And it’s easy to imagine how this evocative sign imprinted itself on Al Aswany’s mind in the many years he walked past it every day to his dental practice in the same building.

The novel — whose wide-eyed, energetic prose chronicles the loves, betrayals and tragedies of the inhabitants of a contemporary downtown building, has sold out several editions in Arabic (Merit, 2002) and English (AUC Press, 2004), while a film version — costing three million dollars and starring famous Egyptian actors Adel Imam, Nour Al Sherif and Youssra — has just been shot. Once the movie hits the screens, the Yacoubian is bound to become a household name.

In fact, it was reportedly the attention surrounding the upcoming film that drove the building’s apartment and business owners to pick up Al Aswany’s novel. What they read made them wish their residence had continued to dwell in obscurity. The novel’s blunt depiction of the sexual and financial exploitation to which its characters subject one other is damaging their reputations, they say. “People call it the building of homosexuality, of prostitution,” laments one of the building’s caretakers, “not the Yacoubian building anymore.”

Residents are particularly upset that Al Aswany has apparently named several of his characters after actual residents of the building. He also gave them some of the same physical attributes and professions, allege the sons of the late tailor Malak Khela, whose fictional namesake is depicted as a ruthless operator who rises to power in the building through currency and liquor smuggling, blackmail, and various other merciless strategies. The building’s caretaker, Fikry Abdel Malek, unhappily discovered a character who shares his first name, and is suing Al Aswany as well as Waheed Hamid, the screenwriter, and the film production company. In a further layer of legal entanglement, Hamid is threatening to countersue his accusers, charging them with defaming him.

While for readers such overlapping of reality and fiction may add an extra layer of fascination (did Al Aswany not just imagine but witness the brutal machinations and dramatic falls from grace taking place behind the building’s anonymous exterior?), for residents such confluences are unsettling, to say the least.

In fact, as is often the case with those who shoot to sudden stardom, the Yacoubian is having some trouble adjusting to its new spot in the limelight. While the owners of neighboring shops will direct you there with a knowing if somewhat mystified smile, the residents themselves are likely to be a bit defensive. The bawwab Mohamed will tell any visitor right off the bat that everything Al Aswany wrote is “lies” (a statement Al Aswany himself would agree with, if by “lies” one means “fiction”). Residents say they are tired of being pestered and asked impertinent questions, and they are mostly unwilling to talk to outsiders.

The residents’ sensitivities, while heartfelt, are also somewhat ironic. As Al Aswany himself says, he was driven to write The Yacoubian Building in great part out of nostalgia for the more tolerant, cosmopolitan downtown of the past, and as a statement against what he perceives to be growing conservativism and self-interestedness in Egyptian society. He claims that his work is fictional and that any similarities between characters and real persons are coincidental, and suggests that his accusers are only trying to cash in on the building’s fame and fortune.

Will the Yacoubian become a literary icon, as visited as the streets in Islamic Cairo where Naguib Mahfouz set many of his novels? Will it end up a symbol of downtown sin or downtown artistry, of creativity or of petty wrangling, of the imperviousness of artistic license or the pressure of social conservativism? Only time and the courts will tell.

Meanwhile, the building, like all well-known personalities, is making others famous by association. The bawwab of adjacent 32 Talaat Harb — where scenes for the movie were filmed, since the crew was banned from the Yacoubian — got to hobnob with starlets and was even recruited for a small role. He is the latest but certainly not the last downtown resident to have his life altered by the Yacoubian’s newfound fame.