Markus Miessen: Eyal, your work allows for an alternative architectural and spatial reading of the Israeli-Palestinian conflict. In your publication A Civilian Occupation as well as the Territories exhibition at Berlin’s Kunst-Werke, you have explored the spatial dimension of the occupation in the West Bank. In a series of articles and studies for openDemocracy.com, you have argued that a coherent mental map of the conflict must include a three dimensional perspective and the introduction of the vertical dimension into geopolitics. Could you explain how verticality has become an important factor?

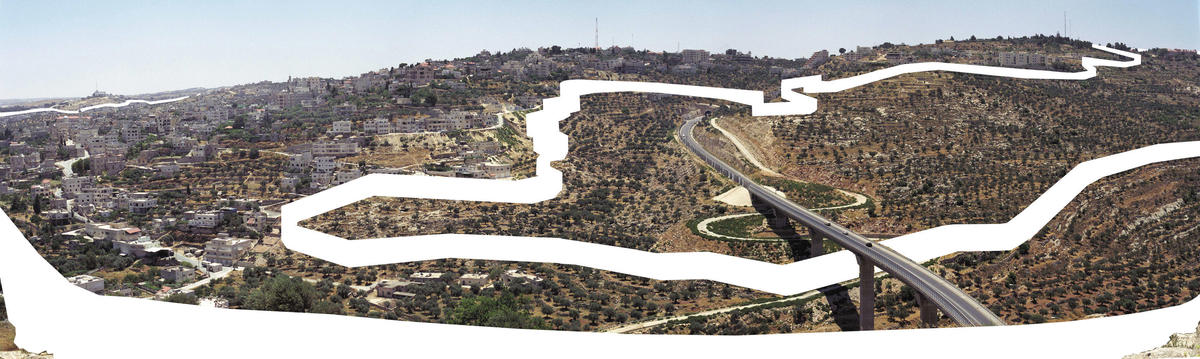

Eyal Weizman: The politics of verticality is the process that fragmented the territory of the West Bank not only in surface but also in volume. Since the 1993 Oslo Accord, the territorial arrangement of the West Bank limited Palestinians to enclosed territorial islands with Israel controlling the sub-terrain (the aquifers) under them as well as the electromagnetic fields and the airspace above them. In this strange logic of partition, the horizon formed a national boundary by separating air from ground and the terrain from sub-terrain. Furthermore, and following this logic, the complete fragmentation of the territory necessitated efforts to physically connect both types of enclaves created: the colonies and Palestinian cities and villages. Since this could not have been achieved on a single surface, it was performed three dimensionally within a volume. Some Israeli roads and infrastructures connect colonies while spanning Palestinian lands as bridges or tunnels. Under these conditions, known since the time of the 1947 partition plan as “the kissing points,” Israeli controlled areas could be above Palestinian ones and vice versa. Currently, the American promise for Palestinian contiguity as a part of a final status agreement is based on the assumption that a similar series of tunnels and bridges could achieve this contiguity for the fragmented Palestinian territory. This state of affairs is what the writer Meron Benvenisti calls the crashing of “three dimensional space into six — three Israeli and three Palestinian.” The current plan for partition includes dozens of kissing points, especially in and around Jerusalem, where the geographies overlap in such intensity. Even the Clinton plan from 2000 implied about forty bridges and tunnels in and around Jerusalem. In this respect, the intensity of the conflict seems to have created a new type of political space, and perhaps even a new way of imagining and practicing territoriality. The politics of verticality is as much a product of a constructed political imagination as it is a physical practice that involves architecture and planning. It fuses Israeli ideological and religious belief in the sacredness of the historical sub-surface (archaeology) and the transcendental value of topographical latitude and the heavens together with a strategic logic of absolute territorial control. By fusing messianic beliefs with military strategy, it is the inevitable territorial product of Zionism itself.

On the other hand, the creation of this conceptual and physical space means that the politics of separation is always going to face a “spatial contradiction.” The term is Henri Lefebvre’s description of political paradoxes embodied in spatial terms. Each one of the territorial layers — the sub-terrain, the surface and the airspace — embodies a different logic of partition. The hydrological cycle moves across and transcends historical borders and ceasefire lines. So does the logic of electromagnetic frequencies and airspace. All attempts to partition this land along simple lines have thus faced spatial contradictions. The layers simply do not overlap.

With the technologies and infrastructure required for the physical segregation of Israelis from Palestinians (the tunnels and the bridges), it appears as if this most complex geopolitical problem of the Middle East has gone through a scale-shift and taken on architectural dimensions. The West Bank appears to have been reassembled through regional politics as if it were a complex building such as a shopping mall or an international airport. If a viable way of managing this conflict does not lie within the realm of design, the logic of partition is doomed to fail. Instead of a further play of identity politics in complex geometry, a non-territorial approach based on cooperation, mutuality and equality must lead to a politics of space-sharing.

MM: Since 1967, the landscape itself was turned into the stage of debate. In what way did the new territorial relationships and their representation affect the way the conflict was waged?

EW: Traditional geopolitics is conducted as a flat discourse. It largely ignores the vertical dimension and tends to look across rather than cut through the landscape. This cartographic approach was inherited from the military and political spatialities of the modern state. Since both politics and law perceive the terrain and other spaces only through the tools available to them (two dimensional maps and plans), borders are imagined as simple lines.

The politics of verticality entails the re-visioning of existing cartographic techniques. Verticality has by now become the common means of exercising territorial control as well as the dimension within which territorial solutions are sought by those trying to find lines of partitions. Consider the way in which Bill Clinton sincerely believed in a vertical solution to the problem of partitioning the Temple Mount. According to his proposal, Palestinians would get the Harram a Sharif and the mosques, and Israelis would control the “depth of the earth” — archaeology underneath them (with oneand-a-half meters of United Nations possession in between).

The Israeli government’s decision to redeploy from the Gaza strip and dismantle the matrix of Jewish colonies and military bases there presents as well a new form of “territorial compromise”: The ground will be handed back to the control of the Palestinian Authority, and the occupation will be transferred to military platforms cruising the skies. Indeed, Sharon’s plans for pullout from Gaza do not include plans for the IDF redeployment from territorial air and water spaces.

MM: The Israeli Knesset refused to obey the verdict of the International Court of Justice. How do you think the United Nations or the international community should intervene in the conflict?

EW: I think that the international opposition to the wall has had — perhaps for the first time in the history of the conflict — some positive consequences. The wall has given international and local opposition a clear target. If the images of mundane, almost benign, red-roofed suburban settlements were not shocking enough to mobilize a global opposition, the images of barbed-wire fences and especially of high concrete walls resonated strongly with a western historical imagination still dealing with unresolved memories of its colonial and World War legacies. You know that the current plan for the wall is very different from the one that was initially proposed. Small victories in rerouting various parts are far from being enough, and in some cases even created damage, but the international community has demonstrated that with concentrated action some facts on the ground can be changed.

In fact, what was effective and must continue is a truly global campaign waged via the UN, the Israeli High Court of Justice, local and international NGOs, the International Court of Justice, the media, and scores of foreign governments. It deflected the gestural sweep of the lines drawn in Sharon’s plan, and it is currently likely to cancel the implementation of the eastern part of the barrier altogether. When I examined changes in the path of the wall, what was made very clear was that micro-political action is sometimes as effective as traditional state political action. All along the path of the wall, the folds, deformations, stretches, wrinkles and bends in the barrier graph the local legal political conflicts in its vicinity and teach us that more pressure on Israel is necessary and effective. One must not only act against the path of the wall and try to deflect it — but against its very concept: These struggles must be joined together and continuous pressure on all levels maintained.

However, we must also remember that the wall is not a single object. It was never able to translate the contradictory forces acting on it into linear geometry. From being a singular, contiguous object it shredded into separate fragments. Like splintered worms that take on renewed life, the fragments of the wall and its barriers started to curl around isolated blocks of colonies and Palestinian towns and along the roads connecting them. Each of the separate shards — termed “depth barriers” by the Ministry of Defense — contained a sequence of fortifications similar to the main part of the wall. In some paradoxical instances the closer the international community placed the linear component of the wall to the international border of the Green Line, the more depth barriers were planned and built on its eastern side, the more fragmented the terrain became, and the more Palestinian life was disrupted. These depth barriers are as destructive to life on the ground as the main barrier, but are unfortunately politically invisible.

MM: Do you think that — in the context of settlements and walls as well as in terms of your research on urban warfare — architects have committed crimes? Should some of them in fact be held accountable?

EW: Indeed. Land Grab, the human rights report I work on with B’tselem, describes work of architects and planners conducted in violation of human rights and international humanitarian law. When planners and architects employ large-scale policies of aggression, control and segregation, and when they make particular design decisions that are explicitly meant to disturb, suppress, or foster racism, a crime is being committed. International humanitarian law is designed to address military personnel or politicians in executive positions. But in the frictions of a rapidly developing and urbanizing world, human rights are increasingly violated by the organization of space. Just like a gun or a tank, mundane building matter is used as a weapon with which to commit crimes.

The nature of the planning action concerned is twofold, including both acts of strategic form-making: construction and destruction. “Design by destruction” increasingly involves planners as military personnel who reshape the battleground to meet strategic objectives, and urban warfare increasingly comes to resemble urban planning. By manipulating key infrastructure — like planners in reverse — the military seeks to control an urban area by disrupting its various flows. Those in charge of bombing campaigns rely on architects and planners to recommend buildings and infrastructure as potential targets. The grid of roads that are as wide as an army bulldozer and were carved through refugee camps reveals another specialty of the planners: replacing an existing circulation system by another, one more accessible to the occupying army and easier in which to control popular unrest.

Although no architect has ever faced international justice, the application of international law as the most severe method of architectural critique has never been more urgent. The legal basis for indicting architects or planners already exists, but architecture and planning intersect with the contemporary conflicts in ways that the semantics of international law are still ill equipped to describe.

MM: Your exhibition and publication A Civilian Occupation was banned by the Israel Association of United Architects [IAUA] in 2002. This caused a major uproar in Israel and a lesser one in the international architectural community. Now, three years later, has IAUA’s thinking changed?

EW: In January 2005 the IAUA decided to react to the continuing debate around Civilian Occupation by dedicating its annual conference to the relation between architecture and politics. They invited all of the participants in the banned exhibition to debate with the association’s members, along with Yossi Beilin, the initiator of the Oslo negotiations, Shimon Peres and the Minister of Education (who each inaugurated one of the days of the conference). I refused to take part, but other participants attended and there was a somewhat heated debate. At the end of the conference, the director of the association publicly retracted the banning, apologized, and accepted the validity of the project’s findings. I find his retraction candid and honest, but unfortunately there were some members who said, “Now that we have finished talking about politics, can we finally go back to talking about architecture?” Some in the association, and indeed in the Israeli architectural community, wanted to use the conference in order to get the issue out of the way and return to the insular and autonomous architectural discourse that was prevalent in Israel before.

MM: Where is your research going now?

EW: I am currently involved in discussions with the Palestinian Authority regarding the evacuation of colonies of the Gaza Strip. The problem concerns the reuse of colonial architecture in postcolonial time, assuming Israel will leave after it retreat some of the structures. The danger, as far as some Palestinian colleagues see it, is that the re-inhabitation of the colonies may reproduce, or at least mimic, some of the power relations in space. If the homes in the colonies are left standing, they may be transformed into “luxury” suburbs just a few minutes drive from congested urban centers. In this scenario, the systems of fences and the abundance of surveillance technology would facilitate their transformation into Palestinian gated communities, reproducing the feelings of hostility and alienation the majority of Palestinians already have for these structures.

Our work concentrates on the idea of recycling architecture — using the structures for a variety of very different ends than what they were originally designed to perform. This recycling could perhaps be understood as similar to the situationist method of détournement. By completely breaking the prescribed relation between space and its use, existing spatial power could be subverted. Moreover, by studying the colonies’ geography, one could abuse their otherwise destructive potential by benefiting from its intrinsic qualities. That colonies in the West Bank as well as in Gaza are independent secluded “islands” connected to one other by a network of sightlines, roads, and infrastructure — what Jeff Halper called “the matrix of control” — may allow for new functions to abuse and subvert their potential connectivity in order to achieve other ends.

We are asking ourselves whether the matrix of control could turn into a matrix of interconnected public institutions of hospitals, schools and universities. Could the small-scale single-family homes be converted, extended, or extruded? Would the grass lawns turn into small agricultural lots? One can surely understand those Pal-estinians who wish to remove the colonies that represented and executed/controlled their oppression, but what could be more of a victory for resistance and perseverance than turning places of oppression into sites of renewed life?

In discussion, two small and rather isolated colonies (Morag and Netzarim) were already designated as public institutions; Morag as a university between the southern twin cities of Khan Yunis and Rafah, and Netzarim as an institute for contemporary culture. Converting a colony of twenty-five single-family homes organized in a circular layout around a core of few public buildings into a university with libraries, offices, laboratories and classrooms is a great architectural challenge. In this respect, recycling the relics of the occupation may prove more environmentally and economically sane, as well as more architecturally challenging, than their direct re-inhabitation or destruction.

Given that colonies could be read as the end condition of suburban sprawl, on more general terms the recycling of the structure of the colonies may raise some subversive thoughts about our own suburbia and its potential appropriation.

Eyal Weizman is an Israeli architect based in London. He is a professor of architecture at the Academy of Arts in Vienna. His exhibition (with Rafi Segal), A Civilian Occupation, the Politics of Israeli Architecture, was banned by the Israeli Architectural Association from the 2002 World Congress of Architecture in Berlin, but was later shown at the Storefront Gallery in NYC as well as Territories in a variety of European art institutions. “The Politics of Verticality” was first published on www.opendemocracy.net.