Sometime, in another life, in another world, he danced in the nightclubs of Khartoum. There were women, lots of them. Empires, kings, and presidents. He saw them all through the lens of a brand-new Arriflex camera. He was the only person to own one in Sudan. His name was Gadalla Gubara, and he was the father of Sudanese cinema.

Then everything went dark. There were only voices, coming over the airwaves. Hour after hour he sat in his chair, resting his head against a radio he held with both hands. He looked like a turtle, head sunk into his shoulders, though he would straighten up suddenly when he heard a song he recognized, and he would sing along, in a voice that belied his frailty. It was that voice, and his hands — pinching my bottom, if I wasn’t careful — that helped me imagine what he must have been like, before.

The cabinets in the tiny one-bedroom house where he lived were filled with the memorabilia of his life, all in careless disarray, useless to him. There were manifestos from the early days of the Federation of Pan-African Cinema (FEPACI), pictures from travels abroad to film festivals in Moscow and Paris and Berlin. Pictures of women. There was a strange intimacy to sitting beside him and looking at photographs he himself could no longer see. The world they depicted seemed far away from the insulting obscurity of his existence.

I was living in Khartoum when I met him, working for Al Jazeera International. For one summer it was my job to go around the developing world, finding stories for The Fabulous Picture Show. Gubara was one of my subjects. He was making movies again, and that was the story: this blind and broken man, almost ninety years old, was the alpha and omega of Sudanese cinema.

Gubara was born in Khartoum in 1920. His father, an impoverished farmer, was part of the extended family of Muhammad Ahmad ibn as Sayyid Abd Allah. Muhammad Ahmad had proclaimed himself Mahdi and led a jihad against Sudan’s Turkish-Egyptian rulers and their British deputy, General Charles George Gordon. The rebellion culminated in the battle of Khartoum, with Gordon slain at the steps of his palace. It was at the Gordon Memorial College that Gubara received his education, earning his school fees by working after class.

Gubara was first exposed to filmmaking during WWII, when he served on the North African front as an officer in the British Army Signal Corps. The British Colonial Film Unit traveled with the troops, screening war movies for infantrymen who’d been drafted from across the empire. One of Gubara’s tasks was to show propagandistic documentaries like Desert Victory, With Our African Troops in the Middle East, and Our African Soldiers on Active Service. Gubara was so impressed by the films’ effect on morale that he sought training as a cameraman. After the war, he received further instruction while serving in Cyprus and London.

When he returned to Sudan, the British Film Unit commissioned him to make educational films about their agricultural schemes — gum arabic production, cotton syndication, and water irrigation. Cinema in local languages was regarded as the best way to reach the mostly illiterate population. Gubara made his way across Sudan with a cinema van, screening documentaries for rural populations, along with more light-hearted films. His time with the mobile film unit confirmed his calling.

“They believed one hundred percent in the images,” he told me. At one screening a man in the audience, alarmed by the sudden appearance of a lion in the film, hurled a spear at the screen; it narrowly missed Gubara, who was standing on the other side. This felt like a story I’d heard before — of French audiences running screaming from early movie-houses as the train onscreen bore down on them. It must have been so exciting to see a film for the very first time. One afternoon we took a ride to one of the villages where Gubara used to pull up with his cinema van. The motorway out of Khartoum is brand new, with endless columns of oil trucks zooming along its length. Thanks to oil, Khartoum today is a boomtown, the whole city a construction site. Osama Bin Laden had a construction business here in the 1990s, when he lived in Al-Riyadh City, a rich suburb of Khartoum. He was an acquaintance of Gubara’s eldest son. Mohammed Gubara knew everyone because he was the director of the Blue Nile Sailing Club. Mohammed also knew Carlos the Jackal, a leftist terrorist who lived in Khartoum in the 1980s, when he was one of the world’s most-wanted criminals. The Jackal was eventually betrayed by his own bodyguards as he lay recovering from minor surgery — for a varicose vein on a testicle — and extradited to France.

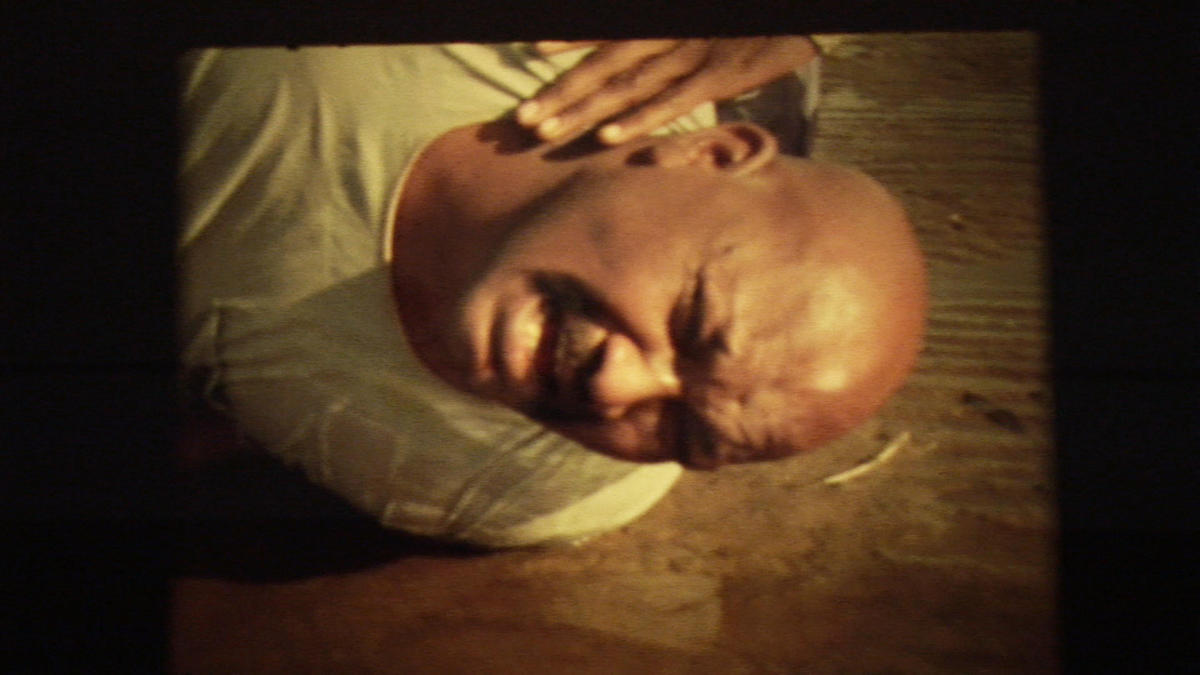

When we arrived at the village, people gathered to greet Gubara. They all remembered cinema vans. One man said he didn’t miss them, now that everyone has television. Gubara, who had lain down on a daybed under a tree, laughed. Another man, more of a cinephile, said that “TV is a small place, where people are alone. Cinema was a big place where everybody came together.” After a mandatory tour around the mayor’s date palm grove on the banks of the Blue Nile, in the most golden of the evening hours, we returned to Khartoum.

On our way back, the sky was suddenly drenched in red light, the air thick with fine sand. A sandstorm! It was almost impossible to see anything, though that did not seem to stop the cars driving at and around us. Gadalla was in the passenger seat, oblivious to it all, whistling a song on the radio. I was afraid and a little bit philosophical, so I asked him how he felt about death. “I prefer to die than to be weak,” he said. “When you’re old, you’re weak. Sexually. Your knees don’t carry you. What’s the point of living?”

That night I stayed at Gubara’s house. I needed a break from his son Mohammed, who would not stop telling me that Darfur is a lie made up by the United States. Gubara was sleeping out in the front yard, and I tried to, as well. We both had colds, and I spent the first half of the night listening to him coughing up phlegm. Later I heard him rummaging through the house, so I got up to help him. I was drenched in sweat and covered in three hundred mosquito bites, mostly on my face. The rest of the night I spent indoors, listening to the howling of stray dogs, waiting for the ventilator to fall onto my face.

The next morning I found him sitting on his bed, without his black sunglasses, his dentures, or his turban. He did his morning gymnastic routine, looking perfectly mad with his arms gyrating through the air. The power had gone out, and we were waiting around for things to start up again. He embarked on a toothless tirade.

“The government doesn’t care if you have water or electricity, there’s nothing at all. They don’t care. It’s too bad. Too bad. The people work hard. They don’t have enough clothing. No one complains. You know why? You complain if you can compare. If you come from Europe, you can compare, but if you live in misery all your life, nothing will move you.” It was the only time I ever heard him complain about the government.

Once, prosperity seemed to be just around the corner. In 1950 Gubara shot the first color film in the history of Sudan. It was about Khartoum as a modern city. The film captures the architecture, the shops, the nightlife, the fashions of the times, intercut with a folkloric performance of a sword dance.

On January 1, 1956, in the People’s Palace in Khartoum, the British and Egyptian flags were lowered and a new Sudanese flag was hoisted. This formal independence ceremony marked the end of two centuries of, first Ottoman, then Egyptian-British rule. The British Film Unit seamlessly transitioned into the Sudanese Film Unit, with Gubara in charge. His first film in his new position, Independence, captured the ceremony. It remains well known in Sudan, an iconic document of the new nation, testament to the hopes and the optimism of those early years.

Gubara’s camera would bear witness to the boom years. Thanks in part to an explosion in the worldwide demand for cotton, Sudan was suddenly prosperous. A railway and an airline were established, and the government wanted the Sudan Film Unit to document it. The 35mm newsreels Gubara made in those years are proud displays of motor cavalcades, military processions, state visits. He produced educational films about the tsetse fly, about black magic. The key words were education, enlightenment, and progress, and the medium was part of the message. Gubara always maintained that nothing was more important than cinema. It was more important than building bridges and hospitals, even, because it could teach people to be self-sufficient, to take care of themselves.

In 1959 the US government invited him to study film at UCLA. He had a great time in the States. He appeared on television, teaching kids about Sudan. He got a pilot’s license and crashed his plane, breaking only his clavicle. Driving with me through Khartoum one afternoon he sang a song by Ray Charles. I got really excited because I’d been thinking since we met that he looked like him. “I used to listen to these songs when I was young and gay and in love and happy,” he said, dreamily. “I’ve got good memories of that song.”

After his studies, he became more interested in cinema proper, moving away from news and educational films. Because there was no industry in Sudan, he went to Cairo to work at Misr Film Studios, the epicenter of Egyptian cinema and the oldest film studio in Africa. Egypt’s storied film industry was in the last years of its golden age, with all the camp and glamour of a fading era, but the example stuck with Gubara. To be successful, he thought, African film would need its own studio system, with its own stars and distribution networks.

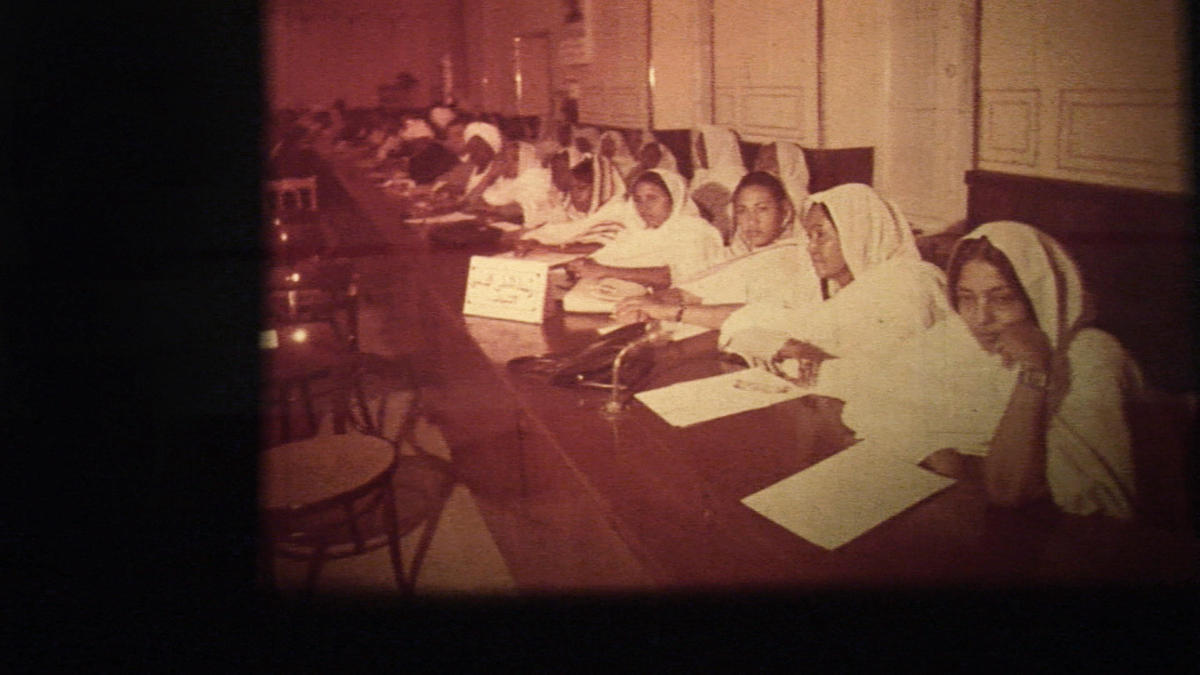

Back in Sudan he struggled to find a cinematic language that could reach people on an emotional level, that could be political without being owned by any particular government or movement. “We must open our eyes and develop a means of resistance,” he told one interviewer. “All films are political. They carry a message. Cinema is a language. If you make a good film, you are understood by society.” In 1969 he was part of a cadre of filmmakers from across the continent that gathered in Burkina Faso in 1969 to create FEPACI. The group included Ousmane Sembène, Med Hondo, and Souleymane Cissé.

Despite his founding role, however, Gubara was always something of an outsider within the almost exclusively Francophone federation. He viewed France’s role in supporting, educating, and bankrolling nearly his entire cohort of African filmmakers with deep suspicion. But filmmakers in Anglophone African countries had no support from hardly any films in those countries, period. Eighty percent of African cinema is in French.

At one point, he worked as a cameraman for Leni Riefenstahl. She had come to Sudan to live among the people of the Nuba Mountains, on the border between South and North Sudan, matching her perfect eye to their perfect bodies. Gubara didn’t know anything about her infamous career in the Third Reich until much later. He just thought she was a funny elderly lady with a bossy voice that he could still imitate to a pitch decades later.

In 1972, Gubara set up the first privately owned film studio in the Sudan, Studio Gad. He put everything into the studio — his energy, his dreams, his savings. He was the scriptwriter, director, editor, and producer. (He was also a pilot, a boxer, a soccer promoter, and a photographer.) He spent nearly all of his time in the studio, until one day his youngest daughter, Sara, was diagnosed with polio.

The doctors said nothing could be done. But one recommended swimming, to stop the muscle from atrophying, so he took her to the pool every day. In the water she could move more freely than on land, where she had to walk with a cane. She learned how to swim. After a few years, she started winning swimming competitions. At some point she outgrew the pool. When she was twelve, Gadalla and Sara went to Capri, so she could compete in the thirty-mile race from Capri to Naples. She saw the ocean for the first time. The salt water made her throw up, and the race was long — twelve hours, without any breaks — but she came in second, anyway. Overnight she became famous. Her father made a documentary about her, Viva Sara, which would become the basis of a feature film of the same name, co-written by Nadine Gordimer.

Gubara’s most famous feature is his first, a love story called Tajouj (1977), a sort of “Romeo and Juliet” set among the Homran of North Sudan, an Arabic-speaking ethnic group. The premise is that the lover must never mention the name of his beloved. When he does, he is made an outcast, and his grief causes him to lose his mind, until an untimely death reconciles them. The village witch is the real culprit in the film, wreaking havoc with her old superstitions. The film, beautifully shot and epic in scale, was very different from the kinds of films his comrades in FEPACI were making — less didactic, yet still engaged. More Hollywood, perhaps, but in Arabic, and unabashedly Sudanese.

The most bittersweet photos I saw of him came from this period, when Tajouj was screened at big international festivals — Berlin, Cannes — and Gubara was on top of the world. Studio Gad was a success, and his dream, to create a true Sudanese cinema to show the world, seemed to have come true.

It was too good to be true, though. In retrospect, the coup was the beginning of the end. In 1989 an army lieutenant named Omar Al Bashir ousted Prime Minister Sadiq al-Mahdi, a relative of Gubara. Many of Sudan’s creative class left the country, but Gubara had too much invested. He kept working on films, even as he found himself under political pressure. The government assigned him a producer to work with — a cousin of Bashir. It went predictably badly. (The rights to Gubara’s 1998 film Barakat el Cheikh are now owned by the cousin.) The political climate disintegrated, with fighting and famine, the resumption of the civil war, and the rise of the Islamic parties.

One night when Gubara was almost eighty years old, he was woken by a knock on his door. It was a pair of policemen, there to inform him that his studio had been confiscated by the government. Gubara was incredulous; but they’d brought proof. He looked at the letter they showed him, then looked up to the ceiling where moments before a neon lamp had been. Now there was only a thin line of light. The news had caused a psychosomatic reaction referred to as hysterical blindness.

When he fought the order, they put him in jail. His studio was turned into an army barracks. His children led a campaign for his release, but when he came out he was a broken man. It wasn’t just the blindness — it was the powerlessness. He had spent his whole life making film, building the studio, and now it had been taken from him. “I felt terrible,” he told me. “I wanted to die because I couldn’t see. I made a big mistake by going into the field of cinema. But I love films. All I ever wanted to do was make them. What can I do?”

It was Sara, his youngest daughter, who got him out of jail and eventually won the studio back, or part of it. To coax him out of his depression, she suggested he should make a new film. She would help. He agreed and got straight down to business, hiring a secretary to type up a scenario — a modern-day Sudanese version of Les Misérables, Victor Hugo’s seminal tome on social injustice. “I had read it more than ten times, and my imagination is very good, so I could visualize a scenario.”

Ironically, perhaps, he applied for funding from the French government. “Any producer who loves his work and understands the game will figure out a way to finance his films,” he explained to me. “From my experience the human being is very strong. If you want to achieve something, you can do it. Provided you’re patient.”

The French agreed to provide the 35mm raw stock. The Iranian ambassador offered to have it processed and printed in Tehran. The rest came from Gubara’s savings, plus money from friends and family.

I still don’t fully understand why the Sudanese government agreed to grant permission. Maybe they didn’t read the script. If they had, they would have discovered that Gubara and Sara had left out the revolution. “Everybody makes their own revolution,” Gubara told me, cheerily. “If you’re treated unjust, you make your own revolution.” He was seated next to Sara in an editing room when he said this, listening to his film.

It was a touch quixotic, the blind octogenarian directing a film — Les Mis, no less — in Khartoum. Gubara’s forty-year-old 35mm camera was called back into service, as was his cameraman, a sweet man named Ali, who had retired from cinematography twenty years earlier. Their light meter had been lost in the occupation of the studio. It’s a pretty essential piece of equipment to get the exposure right, but they decided they would have to work without one, relying on Ali’s eyes.

The result was “Not great, but fair. Not very good, not very bad,” as Gubara put it. “I hope it wins a prize, inshallah. I’ll show it in Cannes and Berlin.”

The lead actors in the film were Gubara’s granddaughter, who played Cosette, and a bald Sudanese comedian with a handlebar moustache — looking like a cross between a circus strongman and a member of the Village People — as the main character, Jean Valjean. Sara did the costumes, the catering, and the location-scouting. Some scenes were filmed in the very jail where Gubara had been imprisoned.

In all honesty, it was pretty overexposed, and the story was sort of falling apart, having been cut down to one hour. Still, Sara said, “I want people all over the world to see this film. Not because it’s a great film. It’s not even a medium film, because it’s so low budget. But it’s something to be shown because we made it, in this situation. I love it because I did it — I know what cinema should look like, but under these circumstances no director can work, no one can do that.” Gubara’s Les Mis was made during the summer of 2007. It was the same summer that Ousmane Sembène, Ingmar Bergman, and Michelangelo Antonioni died. It was as though the century of cinema was fading away. In Khartoum, at least, it seemed as if no one noticed. In the end, Gubara’s film was never released.

He wasn’t discouraged, though. He had other projects in mind, and began preparing a script for his next film, the tale of his ancestor the Mahdi. “To teach the Sudanese about their history,” Sara told me, doubtless echoing him. But it was not to be. One August day in 2008, Gubara had a heart attack, and three days later he passed away, in a hospital in North Khartoum, attended by Sara and two of his other children. The most incredible thing, she said, was the crowds that came to pay their respects. For days, thousands of people blocked the road to his small house — his son-in-law Bella thought there were ten thousand people at the funeral. They’d noticed something after all.

One day near the end of my time in Khartoum, we’d taken a trip downtown to see what was left of Studio Gad. Gubara was in a good mood. He talked about how he hoped Les Misérables might screen in Cannes and Berlin. He asked me whether I was attractive, and if yes, would I play in his new film for the tourism board of Zanzibar?

His studio was surrounded by high-rises, most of them unfinished. We had to cross a little bridge over an open sewage canal, filled with stinking refuse. There was a hand-painted sign announcing “Studio Gad” in Arabic and English lettering. In the courtyard, under a single tree, a homeless man was taking a nap.

Inside, past the trash-strewn courtyard, lovely old equipment stood at the ready, as if waiting to be used again. There was an old 35mm camera — the Arriflex, with its lens missing — and a majestic-looking Italian film-editing table. On the walls there were awards from film festivals, a pilot’s license, and a photograph of a smiling young man in an elegant gray two-piece suit, a camera strapped around his neck, shaking hands with Gamal Abdel Nasser.

And then there was the library. A wall’s worth of film canisters, covered in a thick layer of dust, stacked on a shelf that ran from floor to ceiling. Four of the only eight feature films ever made in Sudan were there, as well as hundreds of newsreels and educational documentaries, some sixty years of work. This room was far too hot for storing celluloid. But until the building could be sold off and demolished, this accidental archive was the last remaining evidence that once upon a time, a Sudanese national cinema had existed.