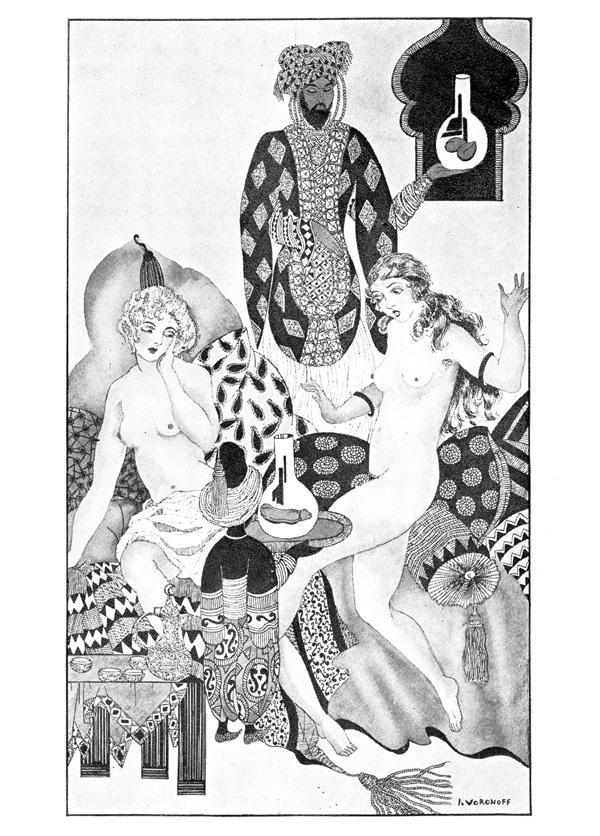

In the 1828 proto-Victorian classic The Lustful Turk, two Englishwomen learn to love their captivity in the harem of an Ottoman dey. The plot has been applied to so many novels, pornos, films, urban myths, postcards, and photo stories since that its moral has seeped into the cultural unconscious; whatever you do, avoid Turkish prison.

Turks weighed heavily on the English mind at the time of its publication, as a result of the Greek struggle against the Ottoman empire. Romantic poets like Lord Byron imagined themselves heirs to a European cultural patrimony stretching back to Greco-Roman times. Byron went a step further than most, heading south and lending his sword to the fight. (He died of a cold in Messolonghi, not quite a martyr to the cause.)

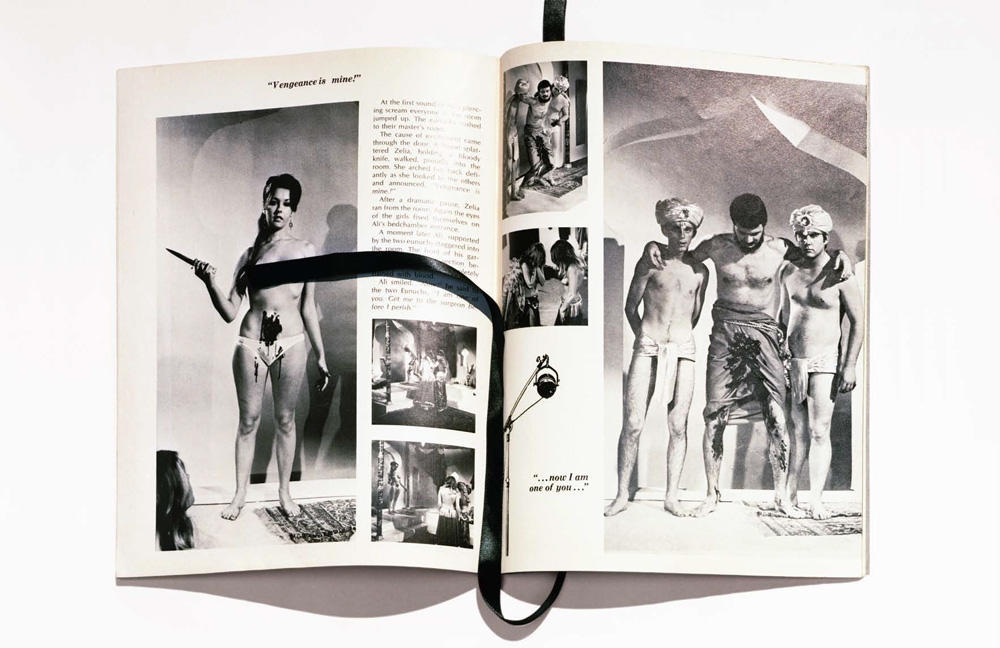

The Greek struggle figures directly into the dramatic conclusion of The Lustful Turk, which was published four years after Byron’s death and four years before the Greeks won their independence. One day the orgy comes to an adrupt end when the lascivious dey moves to take the “second virginity” of the new girl in the harem, a gift from one of his officers. Finding the thought unbearable, the Greek maiden draws a blade and castrates her tormentor before plunging the knife into her own heart.

After tending to his wounds, the dey, in surprisingly good spirits under the circumstances, summons his English roses and presents them with his dismembered member—his shaft and “receptacles of the soul-stirring juice,” preserved separately in winew-filled vases. The girls would be allowed to return home, the eunuch no longer requiring their services.

It is impossible not to marvel at the strange levity in which the dey accepts the caponing of his breech. Is the agency of the Turk so inconceivable to the English imagination that he suffers not the loss of his balls? Be he Oriental, he he Turk — if you de-prick him, doth he not freak out?