Istanbul

The 9th Istanbul Biennial

Various venues

September 16–October 30, 2005

Why stage a biennial if you have difficulties embracing its format? Of course biennials are suspiciously event-driven, but does this characteristic really determine the meaning of the work exhibited? Istanbul curators Charles Esche and Vasif Kortun have composed a rather strict framework, to be taken with a large measure of critical theory. See the artworks, go home and do your homework. I don’t necessarily object to this approach, but it has its problems.

Fifty-four artists and artist collectives is not very much by biennial standards, but it was enough to make the show big. Several works by many of the artists were on view, and it was more or less possible to take in the exhibition and surroundings without suffocating. Seven venues, from postmodern, postindustrial art halls to temporarily empty living quarters and galleries along the main street of Istiklal Caddesi took visitors through several blocks of the Pera but left the famous old town untouched. Istanbul is a remarkable global city, so the curatorial decision to take the city itself as a theme of the biennial was impeccable (although most biennials try to thematize their locations).

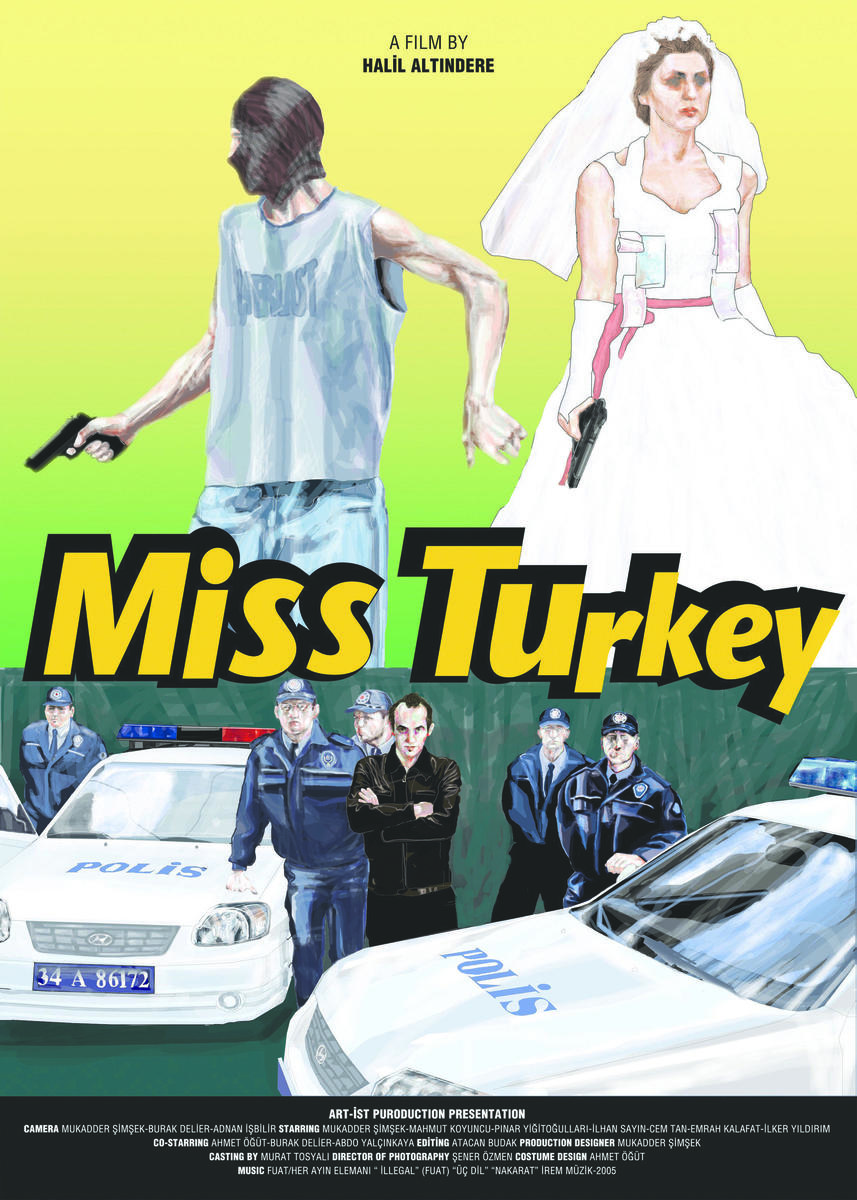

Nedko Solakov’s piece in the Deniz Palas apartment venue worked well with the curators’ desire to look away from historical monuments. In small handwritten notes, Solakov told the story of an absent painting that supposedly had hung on various spots, while all that was left were nail holes, peeling wallpaper and chipped windows. In a humorous way, Solakov’s site-specific piece drew attention to traces of lives once lived in this flat (conveniently used for the exhibition before renovation). Other pieces that related literally to the local setting, like Halil Altindere’s slapstick video of surreal episodes involving a robber, a bridal party and an orchestra along the pedestrian area Istiklal Caddesi, were less convincing.

Much of the remaining art was rather strict: loads of interviews, even a lengthy excursion on the social and economic history of Berlin presented in text and video, supported by models. Visualizing user flows in built environments and pointing at hierarchies of movement and access are favorite ways to engage the politics of a place.

I associate this trend with admiration for the Situationist International (especially its critique of capitalism) and a bit of iconoclasm. References to this 1970s radicalism in the name of relational aesthetics usually share a preference for textual work and built environments in very no-frills form and materials. However material props, or records of social events do not necessarily say much about the social relations themselves. Work by Maria Eichhorn, the Flying Citygroup, Gruppo A12 and Luca Frei, among others, are examples—if admittedly very diverse ones—of ambitious projects with rather vague social implications. Is it the power (or the very powerlessness) of images that attracts these artists? Either way, the exhibition context has a corrupting influence. Critical works become images, which in their turn become ready to be pleasurably consumed by culture tourists. (While speaking about social-economic critique, the exhibition is fairly conventional in its low representation of women artists.)

Perhaps the strategic device of fictionalized fact-narratives is meant to uncover illusions within the current society of the spectacle. Sean Snyder’s real documentary photos from Iraq, Jaron Leshem’s news documentary stage sets from Israel, Michael Blum’s installation of the fake museum for Safiye Behar and Ola Pehrson’s tacky props for a “documentary” on the Unabomber are substantial works individually. But an exhibition situation that juxtaposes so many of these near-, pseudoor drama-documentary pieces, runs the risk of flipping over from a glimpse of realpolitik into a site of cheap, unaccountable political statements.

Most artists, still, retain some belief in figuration and images. Hüseyin Alptekin has imported four fragile plaster casts of monumental horse sculptures from Venice, copies of the ones atop San Marco cathedral. The catalogue entry to Alptekin’s work uncovers layer after layer of meanings centered on the sculptures. The original sculptures were taken to Venice by crusaders from the Sultanahmed hippodrome in Constantinople in 1204. When and how they came to Constantinople is unclear, although perhaps they were moved from Nero’s Roman villa.

Plaster casts were, of course, a pedagogical tool of traditional state-run art academies to enhance and spread civilization through the diffusion of cultural heritage. Knowing this, Alptekin’s video clips on historical equestrian sculptures around Europe accentuate the successful dissemination of the form along with the more suspicious question of their meaning. The work underscores how artworks can be staunchly and notoriously unfaithful to their commissioners, audiences, and enemies by refusing to deliver a steady meaning. Materials perish, meanings change and only the form remains.

A little of the glorious power of imagination was restored by watching the secluded townlets in Solmaz Shahbazi’s light-boxes and films. The artist has visited a selection of gated communities and proceeded to dissect them in interviews with academics. A view of a very conventional and commodified paradise, sure, but also an idea of how to operationalize fiction. Since these unlikely ideal homes really exist, perhaps social critique can transform reality after all.