Does a curatorial démarche deserve its own rubric, or even need to be identified in the first place? With independent curators, the word has come to designate one who thinks and makes sense of artists’ works, one who reflects on, questions and challenges evolving realities in the world of art. A curator is an editor by nature, an author of contradictions and analogies, and an inventor of narratives. In the terms of contemporary art, a curator is the maker of a frivolous present, one soon to become past history. From this point of view — putting administrative tasks aside — a curator’s démarche is not that different from an artist’s.

An artist is in a narrow sense a maker of art products, and in a wider sense a producer and instigator of thought. Concerned with questions of the times, an artist testifies to a present that, once witnessed, becomes social, political, or urban sediment, and once translated into an art form, becomes in its narrow sense myth, and in its wider sense memory.

In November 2000 curator Christine Tohme invited thirteen artists from Beirut to reflect on the recent history of that city’s Hamra Street in what was known as the Hamra Street Project. Out of the thirteen, only six produced site-specific works that were ephemeral in nature — more or less meant for accidental encounters with the general public on the street. These works were installed in different sites along the street itself: in a projection room of an old movie theater and its lobby, in an old café, in another theater and so on. Other works included a single-channel video, an image that was displayed on a rolling commercial billboard, a poem that was published in the form of a postcard-sized book as well as a “mental map” of Hamra that was distributed with the exhibition catalogue.

For a small artists’ community such as Beirut’s (Then and Now),1 the roles of artist, producer, curator and art entrepreneur are not well defined. In the absence of state support for artists and arts institutions, and lacking a robust market, artists and curators have improvised with a balanced working relationship that dates back to the creation of the Ayloul Festival in the mid-nineties. They have shared the little funds available to produce works that communicate thought and create dialogue.

Despite the history of Ashkal Alwan’s past interventions in public space — notably in Sanayeh Park in 1995 and the Beirut Corniche in 1999 — the Hamra Street Project was the first art project staged in such a socially and politically charged historical site. The energy surrounding it was symptomatic of two things. First, despite a strictness in the project’s guidelines, artists’ responses were diverse, and resisted the idea of site-specificity by producing works such as single channel videos, poetry, billboards and maps. As noted above. The artists’ responses to Hamra Street Project transformed the notion of site-specificity into an open forum, and transformed its organizing body, Ashkal Alwan, into a commissioner. The Hamra project was the first of Ashkal Alwan’s projects to have an un-ephemeral component. Not surprisingly, it was also the last of its interventions in public space—perhaps an organic evolution given evolving concerns and needs.2 Second, the Hamra project showed how closely aligned curatorial démarches can be to an artistic ones. Production, organization and making overlap, while the distinctions between them are blurred.

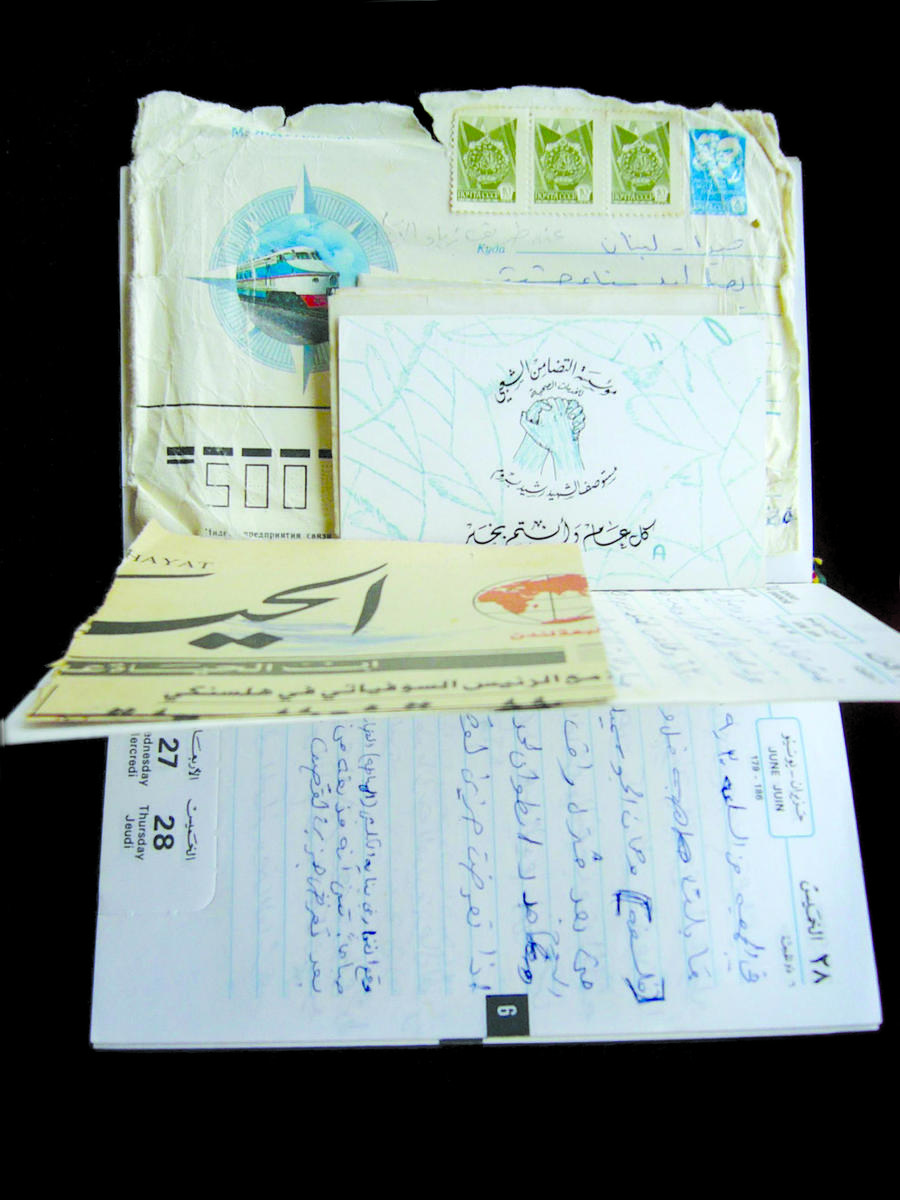

My own work has been circulating in the loosely defined channels of art, committing to different tasks without settling into one realm—swinging between the documentary and video traditions, between the production of art and its teaching and curating. I was also involved in the creation of the Arab Image Foundation,3 which, in addition to preservation, is increasingly focuses on supporting artists’ projects that are based on collecting and studying archival photographs from the region. Working in such an open forum has opened up possibilities in my own work, possibilities often related to the drafting and collecting of documents. Such an influence is evident in two recent works: This Day (2003), which was conceived as a platform for studying images that I have been collecting both in my capacity at the Foundation as well as personally, and In This House (2005), in which I carried out research on the personal documents related to the Lebanese wars. In the latter work, I dig out a letter buried in 1991 by a member of the Lebanese resistance in a garden of the house he occupied for six years.

In the absence of dedicated art institutions, an artist often finds him/herself focused on the development of structures without being an arts administrator or a curator, interested in histories without being a historian, collecting information without being a journalist. It is indeed distracting to be an artist in such conditions, yet it is also an unequivocal privilege to be able to sustain so many positions simultaneously.

Such a blurring of positions and roles is neither superior nor inferior to an increasingly clear-cut assignment of roles. Nevertheless, when a structural reality that is particular to a city (such as Beirut) produces “nomadic” art forums (independent from institutions), the resultant art is often viewed through an unfortunate geographic lens. Such viewing lends itself to the pigeonholing practices of the inter-national art market and, ultimately, limits the realm of interpretation of the work. How better for an artist to resist than to migrate between the rigid poles of the art world by blurring production, curating and education?

1. The exhibition included Rita Aoun, Tony Chakar, Mahmoud Hojeij, Lamia Joreige, Bilal Khbeiz, Nesrine Khodr, Rabil Mroueh (with Fairouz Serhal), Walid Sadek, Ghassan Salhab, Salah Saouli, Jalal Toufic, Nadine Touma and Akram Zaatari

2. Since 2002, and bi-annually, Ashkal Alwan has been organizing a multi-disciplinary arts event held in Beirut entitled Homeworks

3. Since 1997, the Arab Image Foundation (AIF, Beirut) has been funding research and acquisition of — up until now — more than 150,000 photographs from Lebanon, Syria, Jordan, Palestine, Egypt, Iraq, Iran, Morocco and the Arab Diaspora in Senegal and Mexico. Acquired collections are preserved, studied and made accessible to the general public through the AIF database (www.fai.org.lb) and through projects that present a critical and/or historical outlook on the function of the photographic record in past and contemporary times

In each issue, we invite one curator to discuss strategies currently at play in the art world.