Shady El Noshokaty came into his own as a Cairo art world darling in 1999. His solo show was one of the first exhibitions at the Townhouse Gallery; months later he was representing Egypt at the 48th Venice biennale. Central to the self-mythology of the independent art scene in Cairo has been its provision of an alternative to the state’s domination of cultural activity.

This role is validated by the government’s longstanding discouragement of any significant organized activity outside its direct supervision. Noshokaty’s success was rare in its ability to flatter both sides of the deeply ingrained government–independent binary.

He cut a romantic figure. Noshokaty belonged to no camp entirely, produced work with a raw, often personal edge, and, eventually, pioneered new media art studies at a public institution, his alma mater, Helwan University. Though his role since that time has become somewhat less clear and his work has occasionally felt heavy-handed, Stammer (a lecture of theory), a recent video performance, aligned some of the most effective elements of his early and later approaches to art-making.

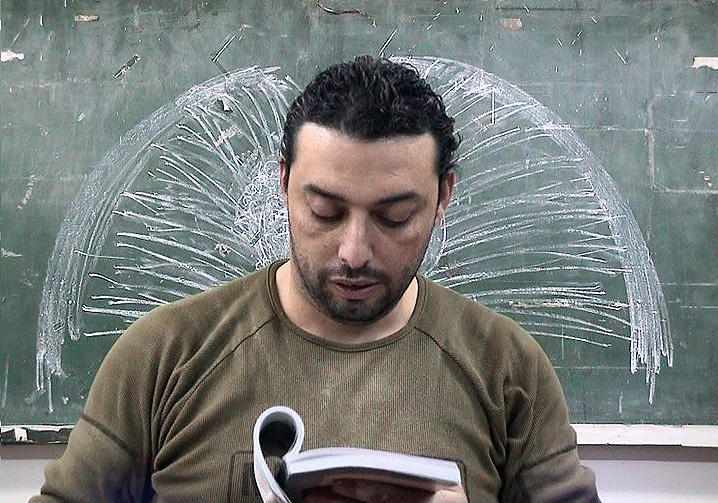

The work premiered last winter at the landmark state-sponsored exhibition ‘What’s Happening Now?’ at the Cairo Opera House — a show notable for including independent artists outside the aging boys’ club headed by Minister of Culture Farouk Hosni. In Noshokaty’s twelve-minute video, the artist adopted the role of the teacher at the head of the class, with the obligatory props and gestures of his profession. The lesson of the day was Property Dualism Theory. He demonstrated an abstract principle, read in Arabic a scientific-sounding phrase, and turned to draw a spiral, which began tight and reasonable but soon grew unwieldy and erratic. “What is the hypothetical relationship between the mental and the physical?” “A crowd gathers to watch the man next door hanging by his tongue from a hook outside the window.” As he repeated them, the sentences became increasingly fragmented. He stared silently at the camera as often as he spoke.

The lack of reference points meant the viewer couldn’t tell what texts Noshokaty was reading from or why. The blackboard drawings looked like diagrams or explanatory sketches but were also inscrutable as such and much more seductive for their combined unreadability and the mysterious aggression with which they were executed. The dissolution of the artist’s language into half-sentences, the intermingling of theory and poetry, and the recurrent lapses into silence all served to obscure a discernable message.

This opacity became a kind of medium in its own right, furthering fundamentally formal goals. Thus, the recurring theme of dualism was reiterated at the level of content but remained weirdly inaccessible until activated by the artist’s performance as a primarily formal phenomenon. At this point “dualism” began to develop its own conceptual weight and texture. This was true to such an extent that when a single tear rolled down the artist’s right cheek, some ways through the video, the occurrence failed to strike this viewer, who cringes easily, as sentimental or superfluous. It seemed entirely appropriate to a lecture conducted without words on the nature of duality and, for those in the know, property dualism theory.

Is it crass to interpret this piece in relation to Cairo’s cultural institutions, state and independent? Such an interpretation, which I find reductive, might go something like this (spoken earnestly): “In a recent video performance, Cairene artist Shady El Noshokaty commented on the reproduction of cultural knowledge and artistic practice as an essentially formal process, stripped of the ability to engage any real content-driven discourse and intended primarily at furthering institutional stability.” Was Stammer in fact a comment on the irrelevance of content in a context wedded to the stability of socioeconomic constellations of people and resources? The question applies equally to the state and independent cultural spheres. Did Noshokaty unveil both art worlds’ ultimate discomfort with content, the investment in an empty, if productive, formalism? While it might ring true, this framing fits awkwardly.

Stammer suggests that these binaries — form and content, government and independent — are both inescapable and irresolvable, a speech impediment and a necessary prop. This staging of a handicapped attempt to articulate a field struck a chord in the context of an Opera House exhibition whose title asks ‘What Is Happening Now?’ Already, the question felt frustrating.

Noshokaty plans to work on a future iteration of the project, titled Stammer Statements, for show in a second exhibition of ‘Occidentalism.’ The work will invoke two audiences — Arabic- and English-speaking — as a response to art market enforcement of an imposed idiom of “Middle Eastern art.” Drawing on a similar choreography, Noshokaty will read one hundred “statements” — phrases, words, the rare full sentence — proclaiming cliché images of life in the Middle East in an intimate tone, evoking again the diary style found in the original Stammer video. While the statements will be read in English, an Arabic language introduction will indicate to viewers who are able to understand the artist’s message that they are the intended audience: they are let in on the joke because they recognize the statements as platitudes. Whether this approach can continue to complicate rather than answer insistent demands for information and explication is another question.