O Calcutta! It’s hard to know, especially if you’ve been weaned on turn-of-the-20th-century accounts of the Indian city, how to feel toward it. Pity? Fear? Macaulay thought Calcutta almost too primitive to qualify as a city, “a place of mists, alligators and wild boars.” Kipling deemed it “one of the most wicked places in the universe.” Later, documentarians and television reporters, especially those inclined to sanctify the work of Mother Teresa, portrayed Calcutta as a den of poverty and squalor, as an endless night that only the celestial light of Christianity could redeem. Leprosy and typhoid, turpitude and soul rot: if a city could be the sum of every snarling, spammy TripAdvisor review ever written, it might look like Calcutta.

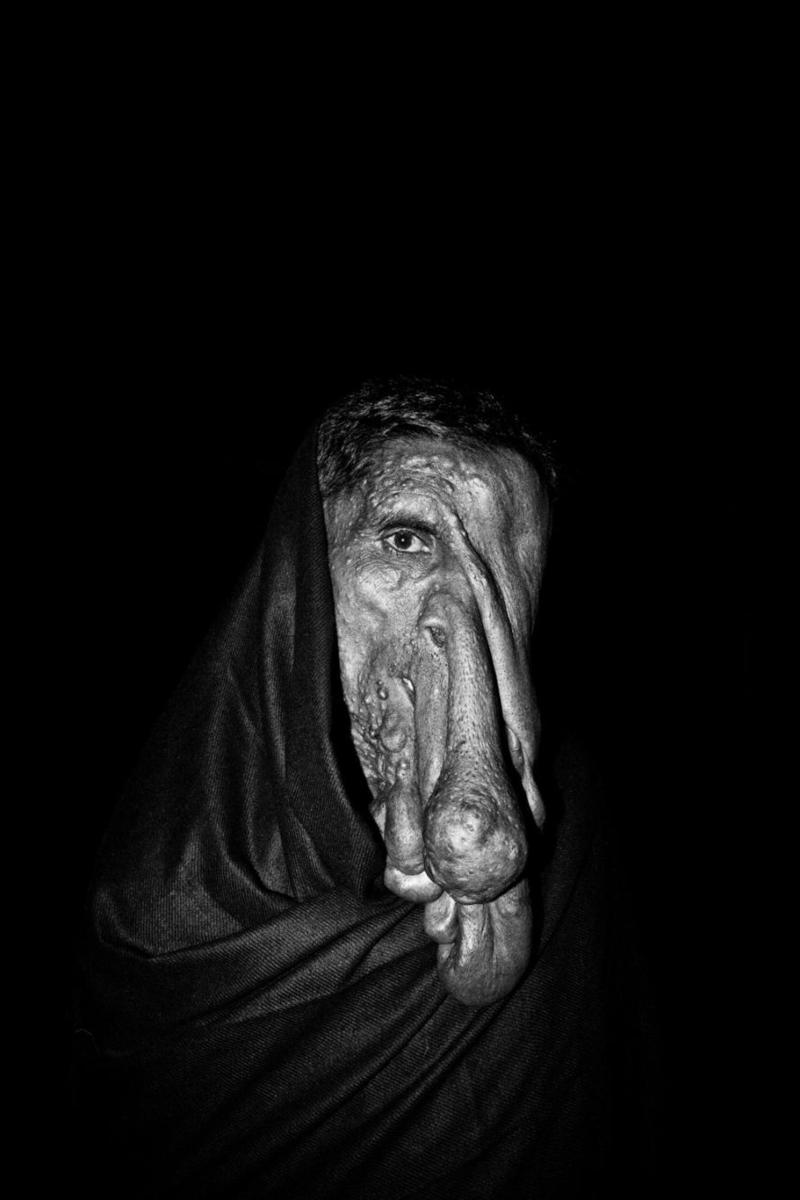

At first glance, Soham Gupta’s photographs seem like more of the grotesque and gangrenous same. His is a cast (and maybe a caste) of city-dwellers — mostly men, more young than old — in various states of infirmity or distress. They wear shabby or filthy clothing. They ooze lesions or ulcers. Those that smile reveal erratic teeth. Some are disfigured by vitiligo, strabismus, or burn marks. One, almost impossible to look at for any length of time, has enormous tumors that resemble drooping testicles, a missing eye, and a clump of swellings where his mouth should be. This latter-day Elephant Man appears as a slur of facial parts.

Here is a man, naked (why?), a stump for a right hand, leaning toward the camera in a posture of permanent imploration. One man holds his penis between finger and thumb: he looks startled — is he mid-piss? Mid-wank? Here’s an older guy, crouching amid a putrefactory stretch of land rife with plastic bags, grungy cartons, and discarded food, filling his face with what might be maggots. Others exhibit enormous foreheads, mysterious smiles, eyes puffy from insect bites or alleyway brawls (or worse). Often there’s an abject androgyny at play: it can be difficult to distinguish the men from the women.

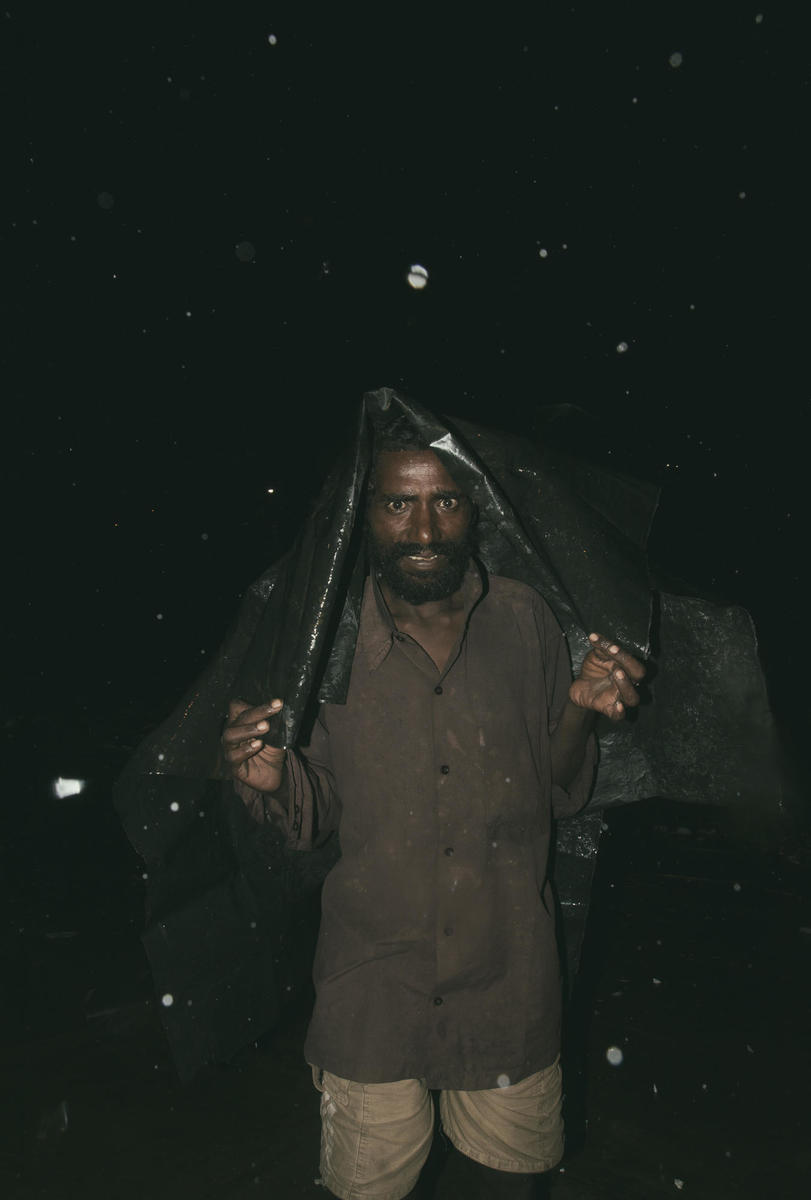

The photographs themselves do not reveal much about the circumstances of their taking. It is always night-time. There is scant backlighting. No street signs or familiar buildings to give us our bearings. No context. Most of Gupta’s subjects occupy — or are stranded in — the frame. They are alone, only tenuously connected to any nocturnal or subaltern community. (To even talk about “community” seems like a romantic projection.) They emerge from an opaque night only to return to it. A shot of a man draped in tarpaulin is ambiguous: the tarp blanket offers insulation; it also looks like a ragged coffin. The whole city has become a black studio in which Gupta’s men and women prowl and perform.

Perform? “All of these pictures are staged,” Gupta has said. I don’t know what exactly he means by “staged,” but for some the very word will set alarm bells ringing. Viewers accustomed to seeing India through a humanitarian lens will be discombobulated, perhaps even disturbed, by these photographs. They’re not exposés or cries for reform, indicting the disparity between the rich and the poor in contemporary India. Do they display a relish for the outsiderdom they capture? It’s easy enough to imagine them being attacked as hipster slumming or some kind of human ruin porn. That was a charge leveled at Iranian-Jamaican photographer Khalik Allah’s Field Niggas (2015), a film that consisted almost exclusively of close and medium shots of the prostitutes, wobbly crackheads, and aggrieved itinerants who hang around the corner of Lexington and 125th Street after midnight.

But what makes Gupta’s work so delirial and discomforting is precisely the blur of real and unreal, real and surreal, real and fantastic. His photobook Angst opens with a suite of six page-sized portraits: the first four depict a man unable to remain upright, steadily floored by exhaustion or intoxicants, at once pitiful but also — whisper it — funny in his uselessness. The sequence concludes with a young glitter-faced, sweat-panted woman, crawling on her knees, licking her arm contentedly — and then a faddishly dressed young man whose evident stupefaction may or may not derive from MDMA.

Angst is full of imagery that seems indebted to social realism and Global South reportage, but hazier and weirder. Gupta’s men and women often recall monged-out ravers, free-festival dowagers, racially indeterminate club kids. (I am reminded of Boy George, in Charles Atlas’s The Legend of Leigh Bowery, describing a particular look as “space age Paki.”) If some of his subjects seem poised between living and dying, between present and future, there are specters here, too, of the street Arabs and lodging-house outcastes of Victorian shilling-shockers and penny dreadfuls; of Hamsun and Munch and the frigid terror of Scandinavian modernity; of Tod Browning and Diane Arbus and Larry Clark and Johnny Knoxville; of the country proles wreaking vengeance on jaded urbanites in Omar Ali Khan’s Zibakhana (2007); of the Gathering of the Juggalos. In one shot, a matted-haired man, his face obscure to us, appears to be clutching an outsized doll; then a thought occurs — perhaps it’s the doll who owns the man.

“In Calcutta,” writes Gupta, “when you have nothing except frustrations within you, life makes A MASTER OF CAUSTIC HUMOR OUT OF YOU.” Gupta’s own writing appears throughout Angst, a book that aligns itself less with classic photo-textual consciousness-raisers such Jacob Riis’s How The Other Half Lives (1890), Jack London’s The People of the Abyss (1903), or James Agee & Walker Evans’s Let Us Now Praise Famous Men (1941) than with Hubert Selby Jr.’s The Room (1971), a novel set in a prison cell and narrated by a nameless wild-tongued protagonist: “They don’t know the terrors that go through your mind as you lie there in the pit waiting for a hint of light to tell you that the night is over.” Often occupying just a fraction of the page, there are micro-vignettes, blurting poetics, sorrowful howls, gibbets of found dialogue, City of Dreadful Night reveries. Bits of the text, printed in capital letters, give off the febrile hysteria of a Chicago tabloid.

Gupta is not interested in developing sociological analyses or grand theories about Calcutta’s immiserated. From their fragmented lives, the improvisatory dances they do to get through each day, the rough-and-tumble of their neighborhoods, he fashions eerie, harrowed text–image portraits that also reflect his own concussed, free-forming inscape. Here everything — the night, its architecture, its denizens — are mutable, mutant, theatrical. Trees and bushes assume corvine shapes, slum dwellers morph into stumpy homunculi, fortified homes become Anglo-Saxon circuit boards. Night is real and night is confected. Soham Gupta is laughing and Soham Gupta is crying. Tragic laughter and bawdy tears. “WHEN LIFE’S HARD,” he writes toward the close, “TIME’S A MOTHERFUCKER.”