Signal and Noise: Media, Infrastructure, and Urban Culture in Nigeria

By Brian Larkin

Duke University Press, 2008

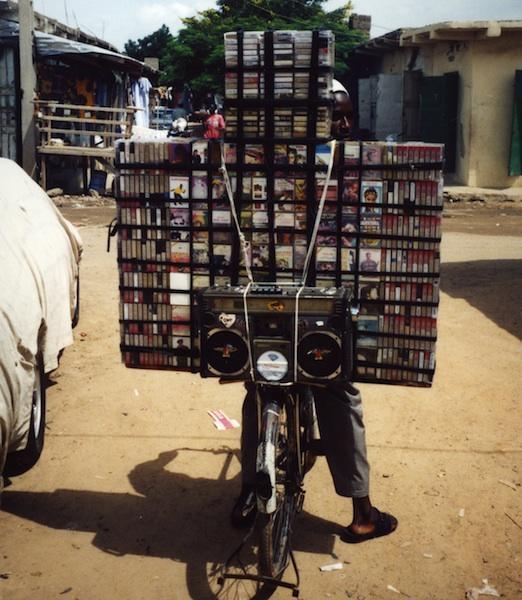

How would we talk about media if Nigeria was our point of departure, and not Europe or the United States? Brian Larkin uses this question to frame his first monograph, a story of colonial development, media technology, and shifting social forms set primarily in the northern Muslim city of Kano. Nested within this story are tales of British colonials introducing the city to the magic of electric lights, mobile cinema units that interspersed instructional hygiene videos with Charlie Chaplin, and half-broken TVs playing poorly dubbed VCDs packed with all manner of prostitution and incest. Thus banal media has come to symbolize postcolonial informal economies — watching an Indian film, the crackle of Hindi voices on a bootleg VHS signifies the degraded quality that mass-piracy fosters; Chinese subtitles overlaid with Hausa Arabic reveal a film’s circuitous route to Nigeria; and the video distributor’s pixelated logo indicates state-of-the-craft computer technology.

In Larkin’s world, the lines between media and infrastructure are blurred. His media theory concerns itself with railways, roads, and electricity. With electrification came radio, which began as a wired and state-controlled operation but was eventually undone by the introduction of wireless, allowing competition from independent broadcasts. Mobile cinema units traveled the newly paved roads of Nigeria showing public service films on agriculture and health care, eventually disappearing with the advent of TV and the increasing prevalence of commercial cinemas.

Both these narratives seem to move from state-controlled, publicly oriented media forms to media designed for private use and individual leisure time. At first glance, this may sound like a tired parable for the decline of the paternal state and the shift to a neoliberal wonderland of capitalistic play — and to some degree, it is. But Larkin reminds us of the complexities of the situation. The technologies at the endpoint of this story — TV, commercial theaters, and pirated video — continue to exhibit traces of their colonial roots in both form and content. The postcolonial state persists in exhibiting its own brand of (often ridiculous) pomp and doublespeak, though the form of transmission has passed from radio through mobile cinema and has now ended up on TV. And the commercial theaters — the few that still exist — are constantly under surveillance by the authorities, who tend to view them as dens of iniquity. One of the book’s most enjoyable sections follow Larkin as he peels away from a theater on the back of a motorbike, hoping to make it into the city before the police start hassling moviegoers.

And of course, there’s also the Nigerian video scene. While previous innovations shifted from colonial control technique to locally made Nigerian media (wired to wireless, didactic mobile cinema to leisurely moviegoing), Nigerian video film debuted with this trajectory already collapsed within itself: films are produced DIY and assiduously pirated. But their content unabashedly displays remnants of colonial imperatives — northern films, for example, often sensationally feature witchcraft and ritual abuse, only to castigate them in the end. This is done to admonish un-Islamic local practices, an approach at least partly linked to colonial methods of control.

A welcome peculiarity of this book is its emphasis on the role of religion. By centering himself in Kano, Larkin avoids reiterating much of the extant literature on Ibadan- and Lagos-based Nollywood video and is able to weave Islam into his story. In the North, an Islamic “film culture” is sought by promoting particular narratives and genres. Melodrama is a favorite for tackling issues pertinent to Islamic life within its generic confines, such as forced marriage or witchcraft. Many Indian films are also accepted, despite ostentatious song and dance routines, as the moral lessons they deliver reinforce ideals of Islamic rectitude.

Larkin is obviously concerned here with media only as it manifests in Kano. His conclusion provocatively deflates the importance of what is commonly referred to as “African cinema.” The films of Ousmane Sembène, Souleymane Cissé, and Djibril Diop Mambéty — names that may be better known in Paris or New York than Dakar or Lagos — live mostly on the international festival circuit and in Criterion Collection reissues, with little impact on the African media world as lived. Larkin claims that these films “construct Africa as being apart from the world, eliding its long historical connections to places elsewhere.” However, media that actually lives and breathes in Africa has no choice but to wear its history on its sleeve — scratched camera lenses signal participation in an informal global economy, and fuzzy radio news is persistent evidence of the failure of colonial development. Larkin succeeds in exposing us to marginal, flawed, and noisy African media forms, the forms that flourish in African urban life, without foreign backers or coproducers.

This is a rare book. Stuffed full of Larkin’s anecdotes and observations of Kano and written with clarity, its academic innovations and arguments are easy to digest. And pictures! Nearly every chapter has some visual accompaniment from Larkin’s collection of Nigerian movie posters, radio ads, and photos from the field. Anyone interested in media, Nigerian film and video, the history and fate of the postcolony, or the informal yet global economies of contemporary city life will appreciate Larkin’s insights.