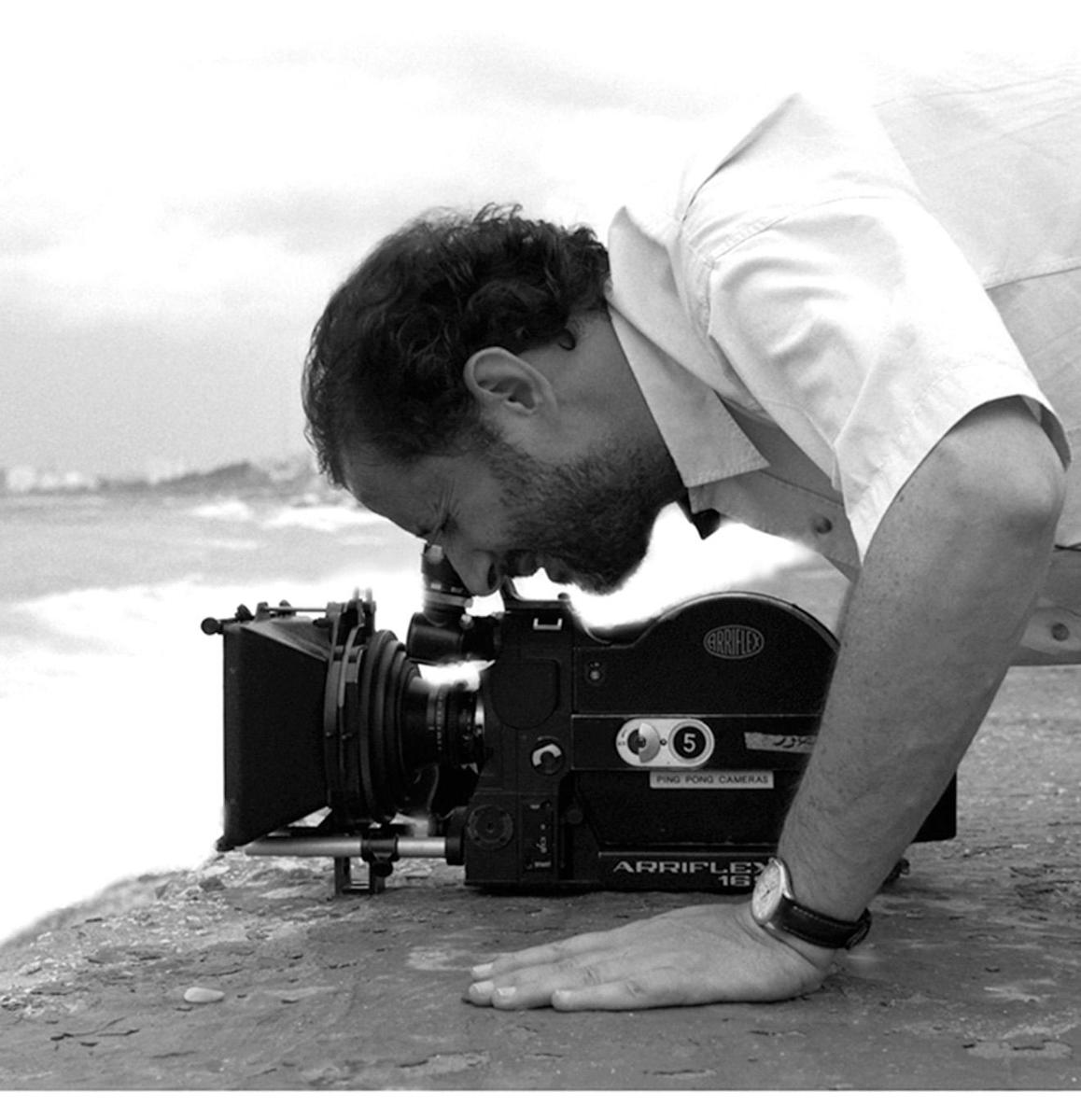

Syrian documentary filmmaker Omar Amiralay is considered one of the pioneers and driving forces of nonfiction auteur cinema in the Arab world. Beginning in the early 1970s and continuing to the present day, his filmography spans more than fifteen films, among them al-Hayat al-Yaomiyyah fi Qarya Suriyya (Everyday Life in a Syrian Village, 1974); Masa’ibu Qawm (The Misfortunes of Some, 1982); al-Hubb al-Maow’ud (The Sarcophagus of Love, 1984); Par un jour de violence ordinaire, mon ami Michel Seurat… (On a Day of Ordinary Violence, My Friend Michel Seurat…, 1996); Tabaq al-Sardin (A Plate of Sardines—or, The First Time I Heard of Israel, 1997); and Tufan Fi Bilad el-Ba’th (A Flood in Baath Country, 2003). Amiralay is an avowed influence on numerous filmmakers across the region, including Mohamed Soueid and Akram Zaatari; recently he joined the faculty of the Arab Institute for Film (AIF) in Amman, teaching classes in screenwriting, directing, and film theory and history. Currently, Amiralay is working on a filmic biography of his grandfather, a former general in the Ottoman army who held high-ranking administrative posts in the “troublesome” late Ottoman Arab provinces, namely Palestine, Yemen, and Syria (Aleppo and Damascus).

You have said that you never intended to be a filmmaker. But were you impressed by cinema, at least? Did it capture your imagination?

I remember the film that impressed me the most as a child: Picnic (1955), with William Holden and Kim Novak. For years it stayed with me, and for the life of me I cannot explain why. I was ten years old, I watched it in a movie theater in Damascus, and it just haunted me. The film is not bad at all. I believe it was regarded as daring in its day. I saw it again as an adult, and while it was an interesting film, I could not elucidate my mysterious childhood obsession with it.

Was the story particularly attractive or unusual, or was it Kim Novak and William Holden?

The plot covers twenty-four hours in the life of a former football star, played by William Holden, who arrives in a small town and seduces a girl, played by Kim Novak, who is either engaged to be married or hitched to another man, I cannot quite recall. At the end, Holden leaves town without having won her over.

Were there no Arab films that impressed you or inspired you to make films?

Documentary cinema in the Arab world is yet a young adventure. When I was of an impressionable age, there was practically nothing in the genre.

What inspired me to make films was actually witnessing the 1968 student uprising in Paris. It was almost happenstance that I had signed up at the Institut des Hautes Études Cinématographiques (IDHEC) in Paris. I had been interested in painting, drawing; then I drifted toward theater. Even when I was a student at the IDHEC, I did not take cinema seriously, even though some of our teachers were master filmmakers, like Jean-Pierre Melville. I could not take fiction cinema seriously.

But the student uprising interrupted my studies. Our courses that spring semester were being held at the Nanterre campus, which is where the revolt began. My late friend Saadallah Wannous and I had followed the students the day they moved from their headquarters at Nanterre to the Latin Quarter in Paris. I was carrying a 16mm camera. We were at the end of Guy Lussac Street when we saw a student in one group stop to pull a cobblestone up from the sidewalk — the road was under construction — and throw it at approaching police. Paris was then lit by gas lamps, and the film in the camera was barely 100 ASA. I strongly suspect that I filmed the first action of this sort by the students. At the end of that day, I returned to the office that students had assigned to media communication and gave them the footage. In the days that followed, I became impassioned with filming more action. I have since come to believe that cinema does not need imaginary plots and characters, arcs and actors. Everyday life, everyday people, large and small, have a lot more interesting stories, in which they cast themselves all the time in a variety of roles.

How about feature films?

Let’s just put the notion of watching someone’s work that “inspired” or “motivated” me to make films aside. In spite of my deep suspicion of fiction cinema, there are feature films made in the Arab world that I appreciate profoundly, experiments I have tremendous respect for. One of my favorites is Bas Ya Bahr (The Cruel Sea) by Khaled al-Siddiq. It was made in 1972 in Kuwait. It tells the story of pearl divers, one of the main sources of income to the native population prior to the discovery of oil. Al-Siddiq learned filmmaking in Hyderabad, and he cast real pearl divers in his film, no actors. The cinematography is fabulous and the storyline very well crafted. You know, pearl divers’ lives are drenched in sorrow, poverty, and tragedy. Al-Siddiq didn’t compromise the vérité tension in the film, nor did he fabricate a narrative that obeyed the imperatives of mainstream cinema. He was pioneering as a filmmaker in Kuwait, but also in the neorealist trend in Arab cinema. There was a captivating poetry in that film — it exuded from the frames and characters.

Has the film screened a lot? Did it mark a generation?

Al-Siddiq was an important and promising filmmaker then. He made two more films and stopped, then he shifted to working in advertising. The Cruel Sea was Kuwait’s first feature film. It traveled to important festivals in the region and in Europe. Al-Siddiq also adapted Tayeb Salih’s The Wedding of Zein, a laudable gesture, in my view, that should be a cue for filmmakers working in fiction because one of the most glaring weaknesses of Arab fiction cinema is that filmmakers are far too seduced by the lure of “auteur total.”

The trouble with this film, as with many other non-mainstream Arab films, is that it is impossible to access them. The notion of a legacy, shared knowledge of Arab cinema across generations and across the Arab world (or even the mashreq) is entirely framed by mainstream Egyptian films. Any knowledge outside that box depends exclusively on individual effort. Where would films like The Cruel Sea screen today? Or even ten years ago? I’ve noticed of late that Arab satellite broadcast entertainment stations like Rotana and al-Shashah have begun to screen a few non-mainstream classics of Egyptian cinema, as well as films from Lebanon and North Africa, from the 1970s and 1980s. It has helped me, and no doubt others, catch up. However, our conversation about The Cruel Sea remains entirely virtual. Can you point to a good Egyptian or Arab feature film, a classic, so to speak, that might have transgressed?

Our generation was lucky in many respects. We were not the founders, we did not bring cinema to our societies, but with the emergence of the auteur and the celebration of subjectivity in filmmaking, we certainly felt this art form was undergoing a revolution, and we were its enthusiastic harbingers. Everything was up for grabs, the history of cinema was ours for the making. We possessed the skills, we created our own language, we established the spaces (like ciné-clubs and festivals) and a discourse (critical writings), and we found our audience. It wasn’t easy. The deck was not stacked in our favor. Not only were we dissident against mainstream culture and market-oriented production, we were also critical of our governments; public institutions were not within our reach. On the other hand, the idea of sponsorship and philanthropy (let alone grant-making international institutions) was not common to our mindset. However, imagining an alternative counterculture was possible, so we established networks of ciné-clubs, we published pamphlets and magazines, we collaborated on each other’s films, and we were in communication with like-minded filmmakers, artists, and dissidents in the region and in the rest of the world. Sadly, however, what we built was shut down, and we have been unable to transmit it to generations that followed. This is why when I defend The Cruel Sea, all I can do is describe it and encourage you to seek it out, I cannot hand you a VHS tape, let alone a DVD. I cannot guide you to an archive…

I understand your frustration. but again, I am too skeptical of fiction cinema to indulge in appreciating what have been declared “classics.”

Why are you so skeptical of fiction cinema? Does that include auteur cinema? You have made reference to the “auteur total” in your reply earlier.

I don’t understand the initial premise. Why would anyone invent a story, ask actors to pretend they are characters, create sets, costumes, when life, history, memory, are a dizzying meshwork of fictions. Every public square, neighborhood, or home is a set, has been designed as such, and is the site of imagined projection and an organization of space and decorum. I have found the contrived fictions in our own cinema to be far less fascinating or captivating than what I witness every day, in my neighborhood, on the street, in the midst of families.

You ask about the “auteur total” — well, it is where I find most of the trouble to lie, a strong penchant that Arab filmmakers have been enraptured with. In other words, they write the script and direct the film. Filmmakers are not necessarily good storytellers, nor can they de facto write good dialogue. The Arab world is rife with extremely wonderful, award-winning, innovating novelists and writers. Collaborations would have been so enriching, so challenging — but most unfortunately, filmmakers have almost systematically turned their backs to them. There are a few exceptions, here and there, but not enough to build a trend, let alone a tradition. Instead we have a corpus of cinema that seems to betray the fantastic complexity of our realities, of how people are, how their destinies are woven.

What about contemporary nonfiction cinema?

It is true that lightweight and low-cost video and digital technology has had a democratizing impact on production — however, what has been lost is discipline and rigor in filmmaking, in approaching the subject. When we were working with 35mm and 16mm, because film reels were very expensive, we could not afford to film sparingly. In documentary, or nonfiction, we spent hours and hours talking to subjects, studying angles, familiarizing ourselves with stories and places, because when it came time to shoot we had only the space of a few takes. This time spent in proximity and profound engagement obviously translated to the final product. Not only did we as filmmakers become involved (if not embedded) in the story, but the ambiguities of each character or situation became tangible. With digital video, that imperative is nonexistent; filmmakers can film for as long as they want until they get what they deem satisfactory. The time invested without the camera filming, that profound engagement, is practically lost. That discipline and rigor in approach is key to auteur cinema.

There are interesting filmmakers, courageous and bold who dare to break with convention. My experience with teaching at the FIC has reinforced my optimism. The hardest part is the deprogramming, or bringing them to some sort of a clean slate where they can begin to perceive cinema, its tools and language, in a radically different light. The second hardest part is strengthening their confidence in themselves and in their subjectivity to dare find a voice, their voice.