Los Angeles

Babak Afrassiabi and Nasrin Tabatabai: The Isle

Mak Center for Art and Architecture

May 28–August 23, 2009

Back in 1978, the Shah of Iran launched an ambitious program to develop a small island into a modern getaway for the use of the royal family and various elites. Just off the southern coast of Iran in the Persian Gulf, the island was called Kish, and there were elaborate plans for casinos, luxury hotels, an international airport, and golf courses, along with the requisite palaces. But the Shah’s planned utopia was never fully realized; it’s rumored that when the Islamic revolution hit a scant year later, locals occupied the vacation palaces. Since then, the island and the various plans drawn up for its future (some realized, many more not) have indirectly charted Iran’s own aspirations on the world stage.

Efforts to define Kish as a free-trade zone, which began immediately after the revolution, were finally realized in the early 1990s, following the Iran-Iraq war — cementing the island’s status as an isolated test site, a working model for new patterns of consumption, international commerce, and image projection. ‘The Isle,’ exhibited at the MAK Center for Art and Architecture, was the last in a three-part exploration of Kish by Nasrin Tabatabai and Babak Afrassiabi, the collaborative duo behind the Farsi/English publication Pages, wherein the artists and a cadre of deadpan German architects they interviewed all proposed development plans for the island, plainly representative of contrasting attitudes toward the failed utopia. Intentionally or not, Pages’s approach at times mirrored the simple problem-solution structure that characterizes a lot of architectural practice. Both active artists in their own right, Tabatabai and Afrassiabi came together as a critical, analytical team to define and respond to the particular problem Kish represents. Whether they succeeded in moving beyond a simple redefinition of the site is unclear. Within the Kish trilogy, which also included Sunset Cinema (2005) and Undecided Utopias (2007), Pages used design and architectural strategies to map the island’s evolution from a sleepy outpost through its development as a pet project of the shah, coming in from a different angle each time. While Sunset Cinema paired a series of Iranian films with an architectural proposal for a Kish documentary film festival, Undecided Utopias brought together topographical models and the series of documentary interviews that were also central to 'The Isle.’ The real focus of 'The Isle’ ended up being the Kish of today, an imagined paradise grabbed at by the competing European architects who appeared in the films. Contemporary plans for the development of the island involve the same painfully essentialist terms of debate that, one imagines, must have plagued Kish from the beginning. The question of whether to make the island into a replica of the Côte d’Azur, or how to distill and inject an “Islamic” essence into a Europeanized framework for luxury living, dominated the architects’ conversation and their models.

I don’t think I was the only one at the Schindler House, where MAK is housed in West Hollywood, who thought a video of a bunch of humorless German architects caressing their many-petaled architectural models of a “Flower of the East” hotel — designed as part of a cancelled 2004 competition to develop a large-scale resort on the island — was an unexpectedly telling (and sexualized) metaphor for Euro-American involvement in Kish’s development. The men’s somewhat regretful presentations of their dissolved projects revealed a Kish frozen in a state of potential, forever a site of projected fantasies. One interviewee dreamed up a secured “enclosure for freedom,” which would suit the needs of an Iran of the twenty-first century (itself largely imaginary to him): a free-trade zone where it would only be possible to “define freedom” under the condition of both being a consumer and living behind a fence. The unsettling implications of this proposition seemed to crystallize in the air between that architect and his partner as they paused partway through to translate the word “checkpoint” — unwittingly describing some kind of post-9/11 resort that would reconcile Bush-era security hysteria and luxury vacationing. Pages proposed alternatives to the architects’ terms of debate in their own texts and models.

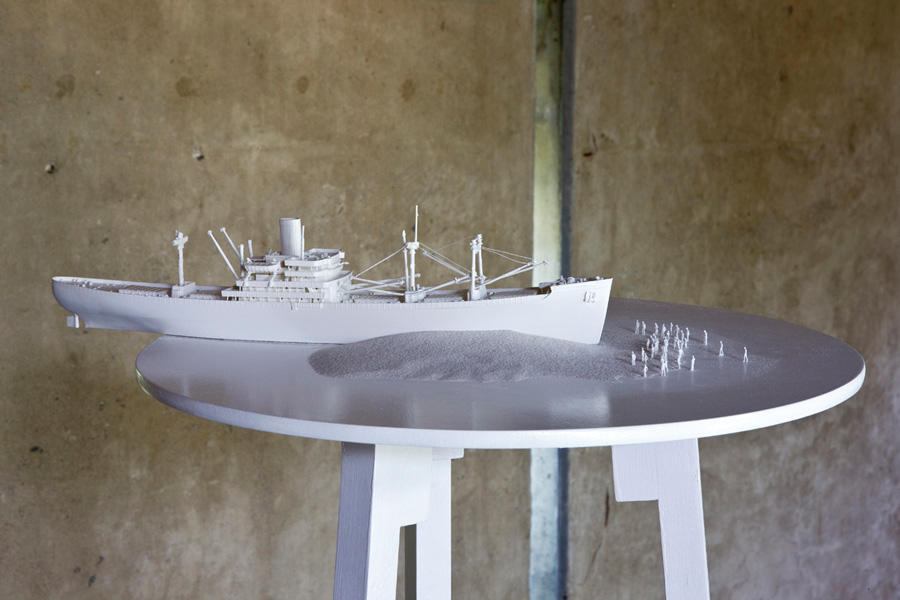

Yet for the most part, the more perturbing implications of Pages’s Kish-centered project remained buried — to the point where it wasn’t always clear why certain objects were included. Re-appropriation of Vogue Paris, February 1978 was precisely that, with vintage magazine pages — some of whose figures had been exacted and isolated to stand out — propped up on a series of tabletop stands. There was a Kish fashion spread, a Kish society page, a Kish vision of travel and leisure. Re-appropriated it may have been, but the sliced photo spread contributed little to a rewriting of Kish’s history. The pages were thin archival traces that had difficulty sustaining the weight of the story they were meant to help tell; cutting into them even managed to obscure the sheer poignancy of the copy trumpeting the island’s “rich past and fabulous future.” Like the German architects it presented with such ironic documentary candor, Pages approached the island of Kish as an abstract landscape. It compiled historical lessons, elevation models, research photographs, documentary interviews, and archival sources to reach a definition of place. There were a lot of inquiries: if the Kish documentary film festival “introduce[d] certain narratives of social consciousness into the escapist fabric of the island,” what kind of architecture would be appropriate to house the event? Sunset Cinema responded to this question with a pristine architectural proposal for mobile projection units; ‘The Isle’ offered a more ambiguous response. In the pseudo-architectural Model for an Island (2009), stiff, shiny silver paper was cut and folded into origami shapes, propped up by the most typical infrastructural basics: satellite towers, construction signs, an oil derrick. It veered between the preciousness of the tabletop object itself, small and sparkling, and the impressiveness of the monument it projected into Kish’s future and our imagination. Model was a parody of impracticality, the stuff of fantasy; it mocked the idea of a clean architectural “solution” as embodied in the Sunset Cinema. But in conjuring up a shimmering, capricious, structurally ludicrous “model for an island,” poised atop sturdy supports, Model also suggested that something else in this whole equation might be a little overblown: the show’s own working definition of Kish as a glitzy utopian Other to the staid, steadying, restricted culture of the mainland. ‘The Isle’ seemed typical of a growing body of contemporary art that aims to turn the unique geographical conditions of a place into an analytical framework with broader implications.

In the case of Iran, and the Middle East in general, this often entails treating histories that may be new to a general audience. Yet sometimes such efforts to establish a record, and simultaneously set it straight, begin to buckle under their own weight. Certainly, those German architects’ eerie conflation of the architectural conceit of a gated community with the notion of political freedom resonated with larger patterns in the contemporary tourism boom in the Gulf region and far beyond. But why push it, and cave to the temptation to make sweeping statements about the state of the world today? After all, there’s a lot to say about the island experiment of Kish alone.