“Hygiene Corner: The Echo of Implicit Western Intervention” was the title of an influential article published in a 1984 issue of the magazine Sahifeh. Its odd title was a reference to a popular 1970s children’s television series, Mahalleh Bihdasht (Hygiene Corner). Throughout the 1980s, conservative magazines revisited the cultural products of the Pahlavi era, producing revolutionary criticism after the fact. The author criticized the show for emphasizing bodily hygiene at a time when the children of Iran lacked what he referred to as bihdasht-i ma’navi, or “moral hygiene.” Hygiene Corner, he argued, was focused on irrelevancies — not touching one’s eyes with dirty hands, for example; it was, in fact, a tool to distract Iranian children from the realities of the larger world, “the poverty of children in Africa and Palestine as well as the emptiness of the lives of Western children.” At the same time, the show was accused of being an imitation of the American show Sesame Street.

Concern for the moral hygiene of children was widespread in those years. In the wake of the revolution and the war with Iraq, the regime labored to create “national heroes” who might serve as role models for potentially wayward youth. While many of those were historical figures from the early years of Islam, there was one boy hero from the present day, Hossein Fahmideh, a thirteen-year-old who volunteered to go to the front and ended up a martyr, hurling himself beneath an Iraqi tank with grenades strapped to his narrow chest. Hossein’s visage was everywhere, on murals and on state television programs. At my school, painted images of Hossein hung in the stairwells, the lobby, and the prayer room, his face the picture of innocence.

But there were not so many heroines for girls in the early years of the Islamic Republic. There was Fatimah, the prophet Mohammed’s daughter, and her daughter Zeynab. But they had no bodies, no faces; there were quotations about what they did but no images or descriptions of what they looked like. There weren’t many images of women then, period. Some girls idolized the pop singer Madonna, whose cassettes could be found on the black market. Others might have admired Marie Curie, whose serious face appeared in our science textbook. But they were not for me. So I began to imagine myself as a man. Once, seething with discontent, I drew myself as a larger-than-life figure with a raised fist, set against the teeming masses at a political rally — an ayatollah’s pose. It was a confused and confusing time. Then Oshin arrived, like a gift, the tale of a Japanese woman who seemed to embody this curious self-image I had constructed: a flesh-and-blood heroine, combining female virtue and male ruggedness, foreign yet not Western. Someone with whom I could identify.

Oshin was the story of Shin Tanokura, aka Oshin, born in 1900, whose sometimes harrowing experiences provided a window onto Japan in the twentieth century. Told through a series of flashbacks and recollections, the series described Oshin’s progress against terrific challenges, from her Meiji-era childhood through to World War II and the American occupation. Her long struggle began at the age of seven, when her father sent her off to another town to work as a nanny, where she was physically and verbally abused. When she finally decided to escape, she became lost in a blizzard and nearly died. Her father sent her away again, another nanny job, and that second apprenticeship was more benign. When she turned sixteen, however, her father forced her to find yet another job, this time as a barmaid, though the bar was actually a brothel. Eventually Oshin ran off to Tokyo, where she found a wealthy husband and became a hair stylist. Even then it wasn’t happily ever after — before the story reached its conclusion, the couple would lose their home in the great Tokyo earthquake of 1923 and their eldest son in World War II. Oshin would be hounded by her in-laws and lose her job. Her husband would commit suicide. Through it all, Oshin would rise, again and again, starting over and hanging tough.

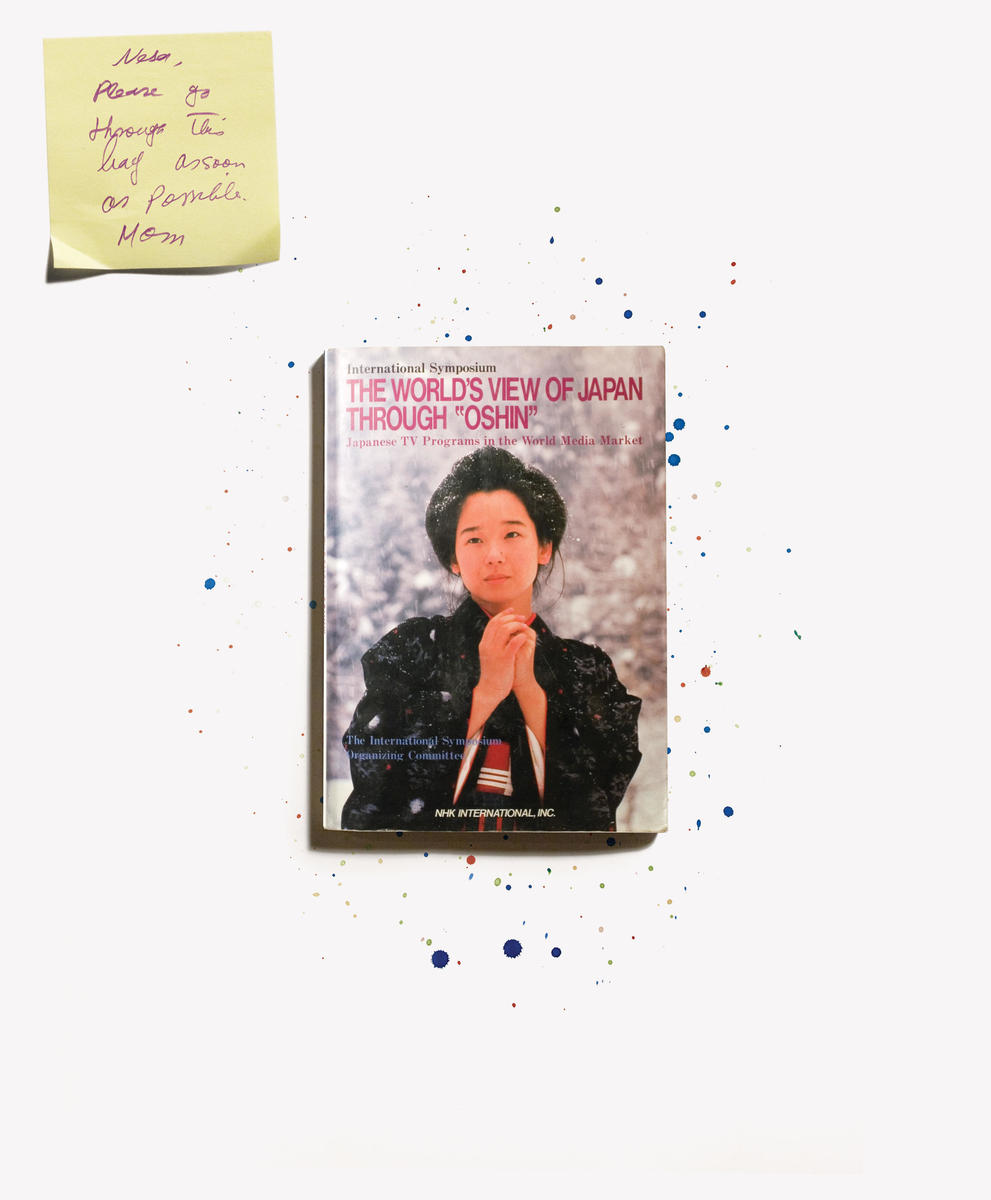

The show was a huge success in Japan. Originally broadcast as a series of 297 fifteen-minute episodes from 1983 to 1984, Oshin was almost immediately repackaged for export and became a global hit, especially in Asia and the Middle East. Iran was one of the fifty-nine countries to broadcast the show. Japanese movies and series were mainstays of state-run television in the Islamic Republic; Kurosawa films were broadcast at least once a year. But Oshin captured the Iranian imagination like nothing else. An edited version of the program ran on Saturday nights over two years in the mid-1980s. The darker elements of Oshin’s apprenticeship were cleaned up, with a few cuts of “inappropriate” scenes and some rewriting of dialogue. Our Oshin was a figure not just of perseverance, but also of virtue.

We knew the story as The Years Away From Home, and there was a sense in which the title seemed to fit not just Oshin’s life story, but also the story of Iran in the 1980s. Normally crowded streets emptied out during broadcasts of the weekly show, while local newspapers reported on Oshin’s life as though she were a real person. The Years Away From Home even became a yardstick for measuring the quality of other TV series. Its moral hygiene (after editing) was impeccable; critics celebrated the show for its portrayal of the “ethics of family life, culinary culture, and childcare.” (In later episodes, Oshin became a successful fishmonger, and her children went on to start a chain of supermarkets.)

But Oshin was popular among younger Iranians primarily because of her beauty. The heroine touched the hearts of teens coming of age under strict Islamic regulations. Teenage boys made little rhymes and limericks about Oshin and other beautiful women from the program and fantasized about what the censors had cut. Middle-school rumor had it that the Japanese original included scenes where Oshin appeared naked in the brothel. Though false, it produced an even more alluring aura around the heroine — a kind of Oriental fantasia, not entirely unlike the European fantasy of the harem girl. Teenage girls did their best to emulate Oshin’s traditional geisha hairstyle, cultivating bulbous forelocks that curled out from under tight headscarves. Kakul Oshini, or “Oshin’s forelock,” was a term used by school authorities to spot those students who failed to implement Islamic standards of the “perfect” hijab. It was a measure of the show’s popularity that the show itself was not blamed for this bad influence; rather, we Iranian girls were at fault for misappropriating the foreign style.

This ambiguity, and Oshin’s curiously privileged place in post-revolutionary Iranian culture, came to a head in 1988, as the war was nearing its bitter end, not long before the death of Ayatollah Khomeini. It was the annual day of remembrance for Fatimah, the prophet’s daughter. Live on the radio, a reporter asked a random person the most banal of questions — who, on that day of all days, was the best role model for “the girls of the Islamic society of Iran?” The girl on the street answered without thinking, “Oshin!” The reporter started to panic. “What about Her Highness Fatimah, peace be upon her?” he asked. His respondent did not take the hint. Fatimah, Zeynab — those ancients were irrelevant to the modern age. The interviewer stopped the program and apologized on the spot. Immediately afterward, rumors spread that the ayatollah himself had been listening that morning; that he had been furious; that reporter and respondent both had been sentenced to death. Later it was announced on the news that the two had been pardoned. Not even the Supreme Leader, it seems, could stay angry with Oshin.