New York

Archive Fever

International Center of Photography

January 18–May 4, 2008

In 1963, Life magazine published a series of photographs by Charles Moore documenting civil rights protests in Birmingham, Alabama. The images captured a moment in which authority gave way to raw violence, as white cops and their dogs attacked black demonstrators. Circulating through living rooms across America, they helped galvanize public support for the civil rights movement and have since become potent icons, testaments to the moral disaster of segregation.

The same photographs have an alternate history, however, as the inspiration and source material for a famous if unusual set of paintings and prints by Andy Warhol, the Race Riot series of 1964. One of these prints — showing a police dog tearing apart a man’s pant leg — was at the beginning of ‘Archive Fever: Uses of the Document in Contemporary Art’ at the International Center of Photography. The works that curator Okwui Enwezor assembled surveyed what has been called, rather generally, the “archival impulse” in contemporary art. Race Riot set the parameters of the show. It not only raised questions about what it means to translate photographic images from documentary sources into the staid setting of the museum, but also, by invoking historical trauma, suggested the ethical stakes implicit in such a move.

Of all the images that Warhol drew from magazines, police reports, and advertisements, Moore’s were the only ones that manifested overt political violence. Rendered with the same deadpan technique as the Marilyns, Death and Disasters, and Soup Cans, Warhol’s Race Riot print didn’t simply re-present Moore’s photograph; it displaced it into another, far more ambiguous, discourse, lacking the moral clarity of the civil rights movement. The subtlety of the image’s transformation from photograph into print, from document into work of art, belied the more substantial shift in how the image is subsequently encountered and discussed.

As Enwezor’s introductory wall text noted, approaching “the archive” is not a matter of unearthing “inert historical artifacts” from a “dim and dusty place.” Instead, “the archive” refers to the structures that actively shape the amorphous bulk of evidence that constitutes the past. Michel Foucault, whose writing looms over the exhibition’s own archival logic, described the archive as a site of authority: by designating what is remembered and, conversely, what is forgotten, it establishes the very conditions of discourse. ‘Archive Fever,’ which takes its title from a 1994 essay by Jacques Derrida, created a platform for some of the strategies the artists used to deconstruct or, in some cases, interrogate and destabilize these conditions.

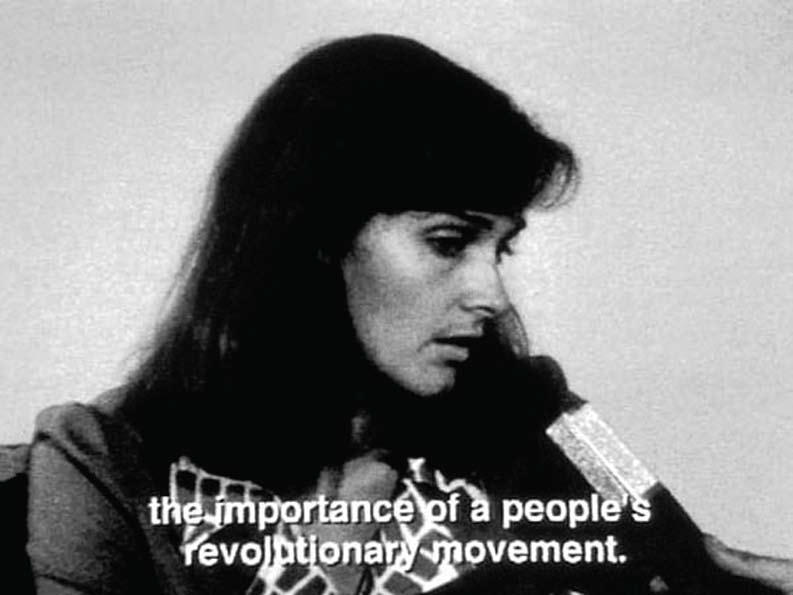

Most of the works in ‘Archive Fever’ appropriated documents of violence and oppression, entering spaces in which collective memory was at once most vital and most contested. Harun Farocki and Andrei Ujica, for example, pored through more than 150 hours of video shot during the 1989 overthrow of Nicolae Ceausescu’s regime in Romania. Their meticulously edited Videograms of a Revolution (1993) brought together amateur video, suppressed broadcasts, and official news reports to weave a revisionist history of the Romanian Soviet Republic’s violent collapse. During a revolution that was indeed televised, choices made in the editing booth immediately informed, even shaped, the political reality being played out on the ground. By re-editing the events, Faroki and Ujica both revealed the ephemeral nature of history and, more important, capitalized on it.

In his ongoing investigations of the Lebanese civil war and its aftermath, Walid Raad similarly rejects totalizing claims on historical representation. In We Can Make Rain but No One Came to Ask, a written narrative about a photojournalist who documents bomb sites preceded a series of unassuming prints in which images of a bombed-out city were collaged in a narrow strip across the top of an otherwise empty page. The overlapping images were barely legible, even on close inspection. Nor were their direct connections to the narrative readily apparent. The piece suggested the complexity of the war by refusing the possibility of gleaning meaning or any concrete semblance of truth.

Raad’s subtle gesture stood in contrast to Hans-Peter Feldmann’s 9/12 Front Page (2001), a full-gallery installation comprised of the front pages of newspapers from September 12, 2001. Feldmann’s displacement of media spectacle into the gallery seemed to do little more than reiterate the point that media is all around us. The more difficult question was how news can be hijacked, manipulated, and reshaped in compelling ways.

‘Archive Fever’ explicitly privileged the role of photographs, film, and video in formulating these potentially disruptive strategies. In works such as Glenn Ligon’s Notes on the Margin of the Black Book, texts also played a substantial role in interrogating assumptions latent in images. Still, some of the most intriguing works in the exhibition were those that managed to pose questions not only at the lofty level of concept but at a tactile level as well.

The simple act of picking up one of Felix Gonzalez-Torres’s posters of gunshot victims, or leaning in with a magnifying glass to study Ilán Lieberman’s meticulous hand-drawn images of missing children, was effective in a way that obviated the need for Enwezor’s extended, at times heavy-handed, wall texts. These works made it clear that although interrogating the “conditions of discourse” remains a rich concept, it may be limiting to discard the spatial and physical sense of an archive as a “dim and dusty place” full of material things. After all, an art exhibition — especially one staged in as iconic an institution as the ICP — comes with its own particular baggage in tow.