“Avoid suspicious places, and none of you should spend time with your mother in crowded passageways, for all those who see you do not know she is your mother (and this may provoke suspicion).”

—From Dubiousness and Rumor; Two Press Vices, Maroof Publications

It was around 10 pm when I asked my friend to call me a taxi. I was going to a party in Central Tehran. The taxi arrived, I climbed in, and we took the long and curvy Modarres highway into the city. Traffic was impossible — it always is — and at about 11, still far from my destination, the driver leaned back and asked, “You mind if I drop you off here?” To my confusion, he added, “I have to rush back home to catch the last bit of Narges on TV.” I had little choice but to get out; my driver looked a bit too much like Reza Zadeh, the Iranian weightlifting world champion. I paid my fare and continued my journey on foot. On the sidewalk, I passed by a couple. The girl was practically dragging her boyfriend along-to, I soon realized, a waiting television: “I hear that Behrooz gets AIDS in Italy and dies, I think it has something to do with his dirty cousin…” I stepped into a store to buy cigarettes and found ten men sitting on cardboard boxes watching a scratchy television. It was Narges again. I waited until the commercial break for them to hand me my pack of Bahmans, smoked a quarter of the pack while watching the last minutes of the show, and went on my way. I’d lost all hope of getting to the party.

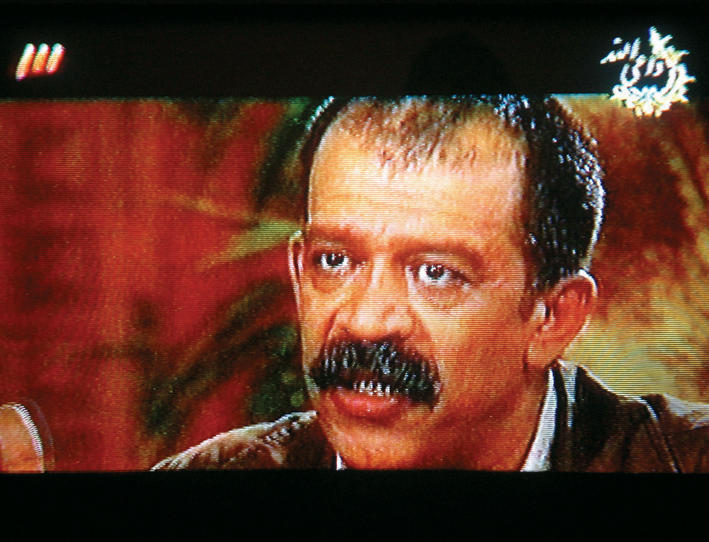

It is said that roughly thirty million Iranians watched the Narges series this past year on IRIB3, thanks to the people at the Islamic Republic of Iran Broadcasting Center-seven days a week and always at 10:45 pm, on the dot. IRIB is the one and only TV and radio broadcasting organization in Iran, its head selected directly by the Supreme Leader (the previous head of the IRIB was Ali Larijani, now the chief nuclear negotiator). IRIB produces a huge quantity of programs each year, from soap opera serials such as Shab-e dahom (a Qajar woman falls for an outlaw and he dies in the end) and Saheb delan (a Ramadan serial that reenacted stories from the Qur’an, also a successful production) to comedies like Pavarchin (the slapstick tale of a family who move from the country to the city; they have weird accents). But of all the programs on offer, Narges, the story of a twenty-something orphan and her travails, has been by far the most popular.

One Iranian blogger divides Iranians into these five categories:

- Those who watch Narges passionately and don’t give a damn about what others think of them.

- Those who don’t watch Narges but don’t care if others do or not.

- Those who don’t watch Narges and tease those who do.

- Those who don’t officially watch Narges because they want to be high-class, but who sometimes watch it in secret.

- Those who don’t own a TV to watch Narges.

On the same blog, a doctor posted his patient’s particulars, collected during a night shift:

…I was watching Narges and got short of breath.

…We were watching Narges and suddenly noticed our mother had fainted.

…Before Narges, doc, I had eaten something, doc.

Narges lives in a house with her sister, Nasrin, and sick mother. Nasrin ends up in a relationship with Behrooz, a rich man’s son, a connection disfavored by both families. They get married in spite of their parents’ disapproval, and Nasrin’s mother dies the day of the wedding. Later, Behrooz travels to Italy illegally, where we are led to suspect he gets HIV (though this is a nasty word and never actually mentioned; he shows the telltale symptoms). Later, we find out that it was only a false threat — a warning of sorts (we have no AIDS in Iran). Narges, for her part, is involved in a relationship with an engineer named Ehsan Saeedi, who recently went through a divorce with a materialistic and ambitious — I’d say seductive, too — woman named Shaghayegh. Rumors fly that Narges and Ehsan got together before the divorce was complete — disgraceful.

Somewhere around the thirty-sixth episode, we see Mansour, a do-gooder engineer figure, pull over his car to answer his ringing cellphone (an educational no-driving-while-talking gesture). In the next scene, we see him lecturing in a nuclear power plant: “Now it’s time for the East to rise… we are in need of a scientific movement.” He launches into a fifteen-minute-long diatribe about the benefits of nuclear energy and an independent energy sector. In a different scene, when she learns that she’s pregnant, Nasrin is pushed by her cruel father-in-law, Shokat, to get rid of her child. She steps into a netherworld where she’s encircled by old hags and shrews. Petrified, she finds her way out and decides to keep the baby, staying true to her morals and God. In the same episode, we see Narges, sporting a chador, happily catching the public bus like any good citizen.

Many Iranians relate to the characters in Narges. We curse Shokat and pray for Narges. We were happy when she got married and cried when her mother died. And besides, what else is there to do at 10:45 pm but watch state television? Especially if you prefer IRIB to the garbage beamed in by Iranians in exile.

Still, the characters on the TV screen appear sterilized. In the world of Narges, threats of sanctions are imperial bluffs; the cops are all righteous; and nonbelievers commit crimes, drive big cars, and send their children to the West. (They usually die or repent their crimes.) On IRIB serials, there is no bribery, no corruption, no abortion, no sex, no alcohol. When there are such things, it’s the doing of outlaws and corporate crooks. In this utopia, you can usually distinguish between the good and evil either by their physical appearance (as if Dante had come with illustrations) or by their choice of words. You see, the creators of Narges are not exactly masters of subtlety. Their version of reality is a carefully managed one.