Missing Soluch

By Mahmoud Dowlatabadi

Translated from Farsi by Kamran Rastegar

Melville House, 2007

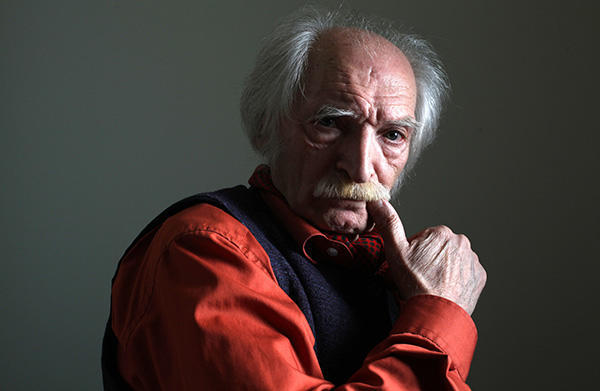

Even as a trickle of Iranian artists, writers, and filmmakers — indeed, even as Iran itself — finds its way into the collective consciousness beyond fear-mongering stereotypes about ayatollahs, hostages, and great satans, a deep reservoir of Iranian culture remains unexplored. Take, for example, the work of Mahmoud Dowlatabadi (b 1940), widely regarded as one of twentieth-century Iran’s most influential writers, but hardly known outside of his country. A leftist who didn’t leave the country after the Islamic Revolution of 1979, Dowlatabadi has remained a strong advocate for freedom of thought, becoming, famously, the target of an assassination attempt in the 1990s, by a rogue unit of the Ministry of Intelligence, that in the end managed to silence at least half a dozen other public intellectuals. Kelidar, arguably his most iconic work, is a sprawling multigenerational tale, five volumes in all, of a Kurdish family. And then there is Missing Soluch, a novel written in 1979 during the bloody days of the Revolution, which has just been translated into English by Kamran Rastegar.

Missing Soluch begins with the mysterious and inexplicable disappearance of Soluch, father of three — Abbas, Abrau, and Hajer — and husband of seventeen years to Mergan, the central protagonist. From this simple premise, the novel radiates outward to transport the reader across a landscape of densely interwoven lives set against the backdrop of an impoverished rural Iranian village called Zaminej. An ensemble of characters, settings, and events comes together to evoke some of the social and psychological conditions of life, love, and loss among a marginal people navigating the unpredictable contours of history.

The narrative arc of Dowlatabadi’s novel is punctuated with great adventures and palpable excitement — gambling! arm wrestling! feats of strength with camels! — and political and social intrigue, as competing families, blocs, and classes within Zaminej struggle to assert their power while the meager agricultural surplus accumulated through cultivating and selling corkwood, melons, and other basic foodstuffs on increasingly barren land grows even scarcer. (A grinding poverty has started to affect the lives of landless peasants and small and large landowners alike.) The novel is also marked by its reliance on an idiom that is both poetic and notable for its inclusion of colloquial aphorisms, including such gems as: “The cat’s prayers won’t bring rain”; “A snake knows the good of your soul”; “But you can’t kill someone for being self-preserving. Goats have hair, and sheep have wool.” This is but a sampling of the various small elements that cohere to lend texture to the story.

Out of stark human drama, Dowlatabadi meticulously draws connections between the harsh economic conditions and social realities facing the inhabitants of Zaminej and the ongoing evolution of their familial and social relationships. Mergan, the pivotal character in the novel, is both a compelling and a contradictory woman, seemingly abandoned by her husband, scorned by some members of her family and her community, yet persevering in order to maintain her livelihood, her sanity, and some measure of control. At times, she is successful; other times, less so. Dowlatabadi situates Mergan at the epicenter of those disruptive forces producing memory and forgetfulness, loss, survival, and individual responsibility.

The evident ease with which Dowlatabadi and his characters move from the most banal activities necessary for survival all the way up to the heights of existential anxiety and revelation creates dramatic tension throughout the novel. The pressures induced by clamorous individual identities and desires are nicely posed against the restrictive but also productive forces of social and familial relationships and obligations. As transformations in land tenure, irrigation, and agricultural production push Zaminej inexorably toward modernity and progress and their attendant displacements, social relations in the village shift. Toward the end of the novel, Abrau, Mergan’s younger son, a headstrong and stubborn figure, becomes a lens through which the reader contemplates the imminent resolution of the story:

[Abrau] no longer saw things as he once did. The earth, his home, his brother and mother, these all had new meanings for him. Something had collapsed under its own heavy weight, imploding, and its bits and pieces were scattered in the shifting dust and smoke. The scattered pieces were no longer recognizable. They were part of the original object, but had lost their original mass. They were now scattered, lacking identity. Each of them no doubt sought a new identity, but Abrau couldn’t recognize them. Among the pieces were Abbas, Abrau, Hajer, Mergan, and — perhaps — also Soluch. These were the elements of their family, but none of them comprised the family on their own. They were all individual elements to themselves.

In the end, the complicated ways in which these “elements of family” interact with one another and with other villagers, in order to find both individual and collective solutions to their problems, are the same elements that make this work such a rich reading experience. Missing Soluch, rendered in lucid translation by Rastegar, who teaches Arabic and Persian literature at the University of Edinburgh, ought to make its mark on the emerging canon of world literature, for its beauty, for its satisfying story, and, above all, for its imaginative horizons.