Fantasy embraces all forms of dreaming. In architecture, it implies a composed, projected environment that is surprising to the eye — a deliberate exercise that tests reality and triggers possibilities for the future. In a sense, all architecture is fantasy. Architectural design is always speculative, since it attempts to specify the future.

Recent progressive architectural projects have generated new forms and expressions in response to new global realities, cultural fascinations, and technological advances. Like their predecessors, the new architectural fantasists move beyond the mundane to transfigure, distort, and extend, and therefore bring new meanings to architecture.

The digital interface: new ways of imaging and imagining

Contemporary culture is led and powered by digital imaging technology, which has transformed the way we visualize and see the world. Architects are now equipped with enhanced tools of dreaming. And as these imaging tools become more sophisticated, the line between the imaginary and the real is increasingly blurred.

In this hyper-consumerist culture, digital/synthetic landscapes are increasingly depicted as “total lifestyle experiences,” ready to be consumed. Be that as it may, digital spaces reveal and/or visualize the unconscious desires of urban spaces, in the sense that imaginary architectural space can be modeled, rendered, animated, and experienced. It brings forth a new set of dreamscapes, mysterious and surreal. This implies a Freudian spatial unconscious, which can be subjected to analysis and interpretation. The tools of digital dreaming, meanwhile, have opened up a window that looks onto the “urban unconscious.”

The tourist city

Historically, the origin of modern vacation time can be traced back to the 1930s, when workers in France, for the first time, were given the right to twelve paid vacation days. Today, tourism has become a “total lifestyle experience.”

The modern tourist resort is by definition a constructed one. The tourist’s perception seems to have shifted away from the pictorial 18th century: There is no longer the desire for the panoramic view. The excessively visual contemporary culture has made everything look familiar. Contemporary tourists are looking for familiarity: They want to feel at home in a strange place.

This has lead to concentrated tourist infrastructures and mega-structure complexes (containing hotel + apartments + mall + cinema + expo + anything goes), which are clustered very close together.

In Dubai there is little difference between holiday accommodation and housing. Architectural programs are becoming fused and undifferentiated. The morphology of the landscape and seascape is becoming fabricated to the point that it may soon be difficult to differentiate between the natural and the constructed. Dubai’s natural beachfront is 45 kilometers long. Artificial islands will add another 1,500 kilometers of beachfront, turning the coastline and the city into an inexhaustible holiday resort. This constructed landscape, like a stage set, provides edited scenes of adventure and entertainment.

The city as non-place

The visual voyage through any contemporary cityscape operates like a continuous shift between eye and mind, as though differences no longer existed between the two. Without a doubt, the city has ceased to be an entity, a place with a specific identity.

Rem Koolhaas, in his well-known essay “The Generic City” published in the Italian magazine Domus in 1994 contemplates the following observations, which pertain so well to Dubai:

Is the contemporary city like the contemporary airport — all the same?

01.6 It is big enough for everybody. It is easy. It does not need maintenance. If it gets too small it just expands. If it gets old it just self-destructs and renews. It is “superficial” — like a Hollywood studio lot, it can produce a new identity every Monday morning.

06.3 The Street is dead.

09.2 The Generic City had a past, once?

10.2 The only activity is shopping…

11.5 Because the Generic City is largely Asian, its architecture is generally air-conditioned.

11.8 The apparently solid substance of the Generic City is misleading. 51% of its volume consists of atrium.

The city has definitely ceased to be a site: Instead, it has become a condition. Perhaps the city has even lost its site: It tends to be everywhere and nowhere. The growing proportion of space lacks meaning because nobody feels any attachment to it.

What used to be the “thrill” of the urban voyage is quickly giving way to banality and exhaustion: One has nothing more to discover, nothing other than immense, general, and nondescript spaces.

Dubai — Twenty-first century visionary architecture/hybrid urbanism

Dubai is an extreme example of urbanism. One of the fastest growing cities in the world today, it represents the epitome of sprawling, post-industrial, and car-oriented urban culture. Within it, large numbers of transient populations are constantly in flux.

The explosion of mega-scale structures and satellite cities provides opportunities for the study of new typologies of building programs and forms. Within the urban grid, and the monotonous and predictable urban condition, the generation of prosthetic geometries and new morphologies acts as a catalyst for innovation. Maybe this is the right time, in the evolution of twenty-first century architecture, to study and adopt new forms and technologies. The aura of optimism and the apparent financial success of the new building boom seem to require fresh, daring architects and designers.

Over the last twenty years, at a remarkable pace, Dubai has developed into a global crossroads. This urban mirage continues to spread out vertically and horizontally without any signs of slowing down. It takes in/purports a vertical urbanism — giant atriums and spidery passages among the towers — curiously set against a background of a sprawling “nothingness,” the desert.

To the visitor, this cosmopolitan city might seem peculiar and hyperactive, with no layering or apparent hierarchy. Its allure lies in its ability to adjust rapidly, in its complexity, in its contradictions.

The city tends to be everywhere and nowhere at the same time, because it has no urban center or core. Dubai thrives on newness and bigness, in an act of ongoing self-stylization and fantasy. Hence architecture is crucial, for it defines these elements. Little more than a grand-scale shopping mall, the city is comprised of “mind-zone” spaces, and of airport-like lobbies. In this theme park orientated cityscape, there is no differentiation between old and new. Everything is recent. Yet everything seems to point to the twin towers of consumerism and tourism.

Here, architecture and interiors act as interfaces to consumerism, to the act of purchasing, to the ephemeral experience. Interior shopping spaces are ever larger, more luxurious and seductive. The advent of air conditioning liberated the architectural form and gave rise to a new set of formal possibilities.

Dubai is a prototype of the new post-global city, which creates appetites rather than solves problems. It is represented as consumable, replaceable, disposable, and short-lived. Dubai is addicted to the promise of the new: It gives rise to an ephemeral quality, a culture of the “instantaneous.” Relying on strong media campaigns, new satellite cities and mega-projects are planned and announced almost weekly. This approach to building is focused exclusively on marketing and selling.

As the visionary architect Cedric Price noted in an interview in 2001, “The actual consuming of ideas and images exists in time, so the value of doing the show betrayed an immediacy, an awareness of time that does not exist somewhere like London or indeed Manhattan. A city that does not change and reinvent itself is a dead city…”

Dubai’s recent development has put it on the map of iconic projects, of real estate prospecting and holiday dream destinations. Yet what is missing is the visionary realization of its architecture. Now is the time for architectural projects to be innovative and original. Now is the time to initiate a much-desired discourse about the face of the city.

A historical perspective: a desert waterfront

Dubai began life as a small port and collection of barasti (palm frond) houses clustered around the Creek. Not endowed with abundant fertile land, early twentieth century settlers set about making their living from the sea, concentrating on fishing, pearling and trading. Commercial success coupled with the liberal attitudes of its rulers made the emirate attractive to traders from India and Iran, who began to settle in the growing town. This gave the city an early start before the explosion of wealth brought on by oil production in the late 1960s.

The trajectory of the development of Dubai is reflected in its population, which has grown fifteen-fold since 1969: from 60,000 then to well over one million today. It is projected that, by 2010, Dubai’s tourist trade will accommodate around fifteen million tourists per annum, serviced by more than 400 hotels. Comparisons are telling: in 2002, Egypt, for example, had 4.7 million visitors, and Dubai 4.2 million. (The former, of course, hosts “real history,” against the latter’s Las Vegas version — including, in the next few years, the construction of a set of Pyramids in the vast theme park Dubailand.)

The emirate’s expansion has followed the Los Angeles model: New developments sprout in the desert, beyond the older cores of Deira and Bur Dubai, linked by freeways and ring roads. The open spaces left in between are gradually filled with a lower-intensity, car-dependent form of urban sprawl.

Since Dubai has no real urban history, it has had to invent a variety of new urban conditions. Using its transitory oil wealth, the emirate has built “free zone” areas, promoted as clusters defined by economic liberalization, technological innovation, and political transparency. Jebel Ali Free Zone, an industrial and trading hub, was followed in the late 1990s by three sprawling industrial parks: Internet City, a bid to make Dubai the Arab world’s IT hub; Media City, which aspires to replace Cairo as the Middle East’s media capital while broadcasting the emirate’s vision of openness; and Dubai International Financial Center (DIFC), a stock market headquarters meant to match those of Hong Kong, London, and New York.

While the desert is usually considered barren and worthless, Dubai’s “empty quarter” has unique real estate value, thanks largely to two companies: Emaar Properties (founded 1997) and government-owned Nakheel. Among many residential projects, Emaar is currently developing the 3.5 kilometer–long Dubai Marina behind the existing Jumeirah beachfront hotels. A high-rise city-within-a-city and home to more than 40,000 residents, it is set to become the focus of the New Dubai. Nakheel has become synonymous with The Palm, Jumeirah, a 5 kilometer–long, reclaimed island. Other Palms and islands are currently being “planted,” in the massive undertaking of transplanting the desert into the sea. The latest project, Dubai Waterfront, will not only add 375 kilometers of new beachfront but will include the largest man-made canal carved out of the desert. By 2002, when freehold property rights were established in Dubai, allowing foreigners to buy property for the first time, the stage had been set for a real estate boom.

Projects

If Rome was the “Eternal City” and New York’s Manhattan the apotheosis of twentieth-century congested urbanism, then Dubai may be considered the emerging prototype for the twenty-first century: prosthetic and nomadic oases presented as isolated cities that extend out over the land and the sea.

Yet, while Dubai is perhaps becoming architecturally the ultimate fantasy city, it has not provided many opportunities to innovative architects. Most of the new projects do not push the boundaries of design innovation. They stay within a safe range of design styles that are palatable to the masses.

Bidoun invited a group of international architects to project their architectural vision onto the city of Dubai, to elaborate on possible scenarios, fictional narratives and forecasts. Their respective visions are found on the following pages.

Terminal City: A project proposal for superlative architecture in Dubai

L.E.FT, New York

Modern Dubai is littered with architectural monuments that can be labeled as superlative architecture: an architecture that breeds on the next big thing — from the shock of the new by comparison to, and referential scale with what has just become old.

In Dubai everything will soon be outdone, a taller, bigger, and larger structure will quickly be erected. What is here today is almost immediately to be irrelevant, insignificant, not worth mentioning tomorrow.

With superlative architecture, “what if?” — a present state of possibility — is replaced by “now what?” — an afterward state of wonder in doubt. There is no more aspiration, no more imagination.

Our proposal, Terminal City, collapses the “city” experience into one building. There is no more city fabric, no more blocks, no more street, no more lots, no more center, and consequently no more suburban spread and peripheries. This new city, caught vertically between two airport terminals, is the last structure that modern Dubai will ever need.

Based on Dubai’s business and demographic models (catering to less then twenty percent nationals), it is a transient city wedged between constant arrivals and departures; with airports on the roof and the ground the city becomes groundless, non-contextual, and a continuous duty-free experience, capitalism at its best, or worst.

Once checking out of the terminal, one can only be on the way to checking in again, that is, on the way out. In between, a vertical city stretches, with all living working and entertainment amenities a city holds. Terminal city even has a cemetery, which, located at the center of the structure, is the furthest point away from any gates.

Terminal City structure is shaped by the overlapping geometry of the airplanes trajectories from Dubai to the rest of the world (using the Emirates Airlines as our model). Resisting any iconographic connotation the structure can only be read as the seminal symbol of what Dubai should ultimately represent: the first true global metropolis in the desert.

L.E.FT is a design collaborative dedicated to examining the intersections of cultural and political productions as they relate to the built environment, established in 2001 by Makram el Kadi, Ziad Jamaleddine, and Naji Moujaes in New York. With an interest in diverse programs, a focus on unconventional interpretations of the ordinary is posited as a design onset. L.E.FT has had exhibitions at Parsons School of Design, Rhode Island School of Design, Storefront for Art and Architecture, and Artists Space, and collaborated with Lewis Tsurumaki Lewis and OMA on competitions. L.E.FT received an honorable mention for Surround Datahome in the 2001 Japan Architect Shinkenchiku competition, and is a recipient of the 2002 Young Architects Forum Award from the Architectural League of New York.

Why are we still learning from Las Vegas?

WORKac, New York

At the turn of the century, Dubai counted 1600 inhabitants. Today it has almost one million. The growth in population is rivaled only by its growth in garbage: Dubai’s domestic refuse increases annually by ten percent with an expected two million metric tons in 2008. As Dubai has developed, its strategy has been to “x” its buildable surface, “y” its population and “z” its trash, to parts unknown.

This incredible boom is said to have come as a result of running the young emirate like a corporation. To attract businesses, Dubai conceptualizes islands of work it calls “cities,” “villages,” and “zones,” immediately linking its business ambitions to urban ideas. Like an archipelago of emirates themselves, these working hubs — Media City, Internet City, DAFZ, DUCAMZ, Knowledge Village — are all designed to perform at the highest competitive level possible. Each island provides everything from cutting-edge technologies to plug-in office spaces, move-in apartments, and financial breaks. Foreign ownership is encouraged — at least of businesses. Attracted by such promise, a young ambitious and smart work force moves to Dubai and by 2003, there were 203 different nationalities living and working in Dubai — constituting eighty percent of the overall population.

At first glance, these “cities” are more akin to American suburban office parks: generic oases of corporate boxes loosely organized around central parking lots and the occasional green lawn. Yet stepping out of the car, it is only a matter of seconds before this first impression is dissipated by the scale of the enterprise and its success. From MSNBC to Reuters, Sony, Zen TV, Middle East Business News, CNN, UNI TV and others, it seems everyone is here and working together. The energy is high and the rhythm upbeat; far from the nonchalant Middle Eastern tempo. While infinite possibilities crowd the imagination, the excess of life witnessed renders the architecture once again irrelevant. Whereas Las Vegas attracts gamblers, Dubai attracts entrepreneurs, and their needs are solely virtual.

Firmly grounding its image as a modern working city for the young and the bold, Dubai generates new typologies for itself. A hybrid between the Champs Elysées and a Manhattan Avenue, Sheikh Zayed Road is a single majestic gesture flanked by skyscrapers on either side. Like a trail in the snow, there is nothing behind the skyscrapers but more desert. This is Dubai at its best, where pure vision and the desire for density yield a fantastic urban moment in the midst of nothingness.

With the advent of the Palm Islands — I, II, and soon III — Dubai reveals its weakness. While proving once again the breadth of its vision at an urban level, it fails to provide the same invention at the architectural. In plan, and from the moon, the Palms are the result of a simple yet genius observation: If a coast line of length ‘l’ is artificially rippled into ‘x’ number of fingers, the length of beach front within a given area is multiplied by ‘x.’ This rippling in turn offers an evolution of the “front yard–back yard” suburban dream: “beach yards” for everyone. Once at the level of the Palm’s streets, however, the inventiveness is stifled. The Palm’s extruded buildings are an ode to “Lifestyle” where theming takes over living in a cacophony of staged styles. From the Asian, to the Tuscan and back to Venice, the Palm is but an architectural Epcot Center where all is fiction written by developers, even one’s life.

Today, in the battle between real life and its theming, it seems the latter is taking the lead. No longer satisfied with being the destination of choice for an incredible work force, Dubai is already launching its next big thing: Tourism — the same next big thing as for so many other cities. After building islands of work, and islands of living, the time has come for islands of leisure: entertainment for all and the creation of fantasy worlds ensuring consumption ad nausea. Disney has finally landed in Dubai.

In October 2003, Dubailand is announced: a five-billion-dollar mixed-use theme park, whose area will equal the current built surface of Dubai. The three-billion-square-foot project is expected to attract fifteen million tourists annually. Amongst the most extravagant projects of Dubailand is the creation of Eco-Tourism World — a green haven of sixteen different gardens, outdoor amphitheater, health spa and resort and academy for 1,000 students. The project’s centerpiece is Al Barari — an oasis of green that will extend over 14.6 million square feet. “Surrounded by, and bordering a protected wild-life sanctuary [it] will truly be an inspirational setting reminding one of the Thousand and One Nights stories.”

If ecotourism was invented to encourage developing countries to preserve their natural wealth, to promote sustainable growth and to support local businesses and education, how are bottomless “thirsty” projects like Dubailand and fifteen million new tourists expected to preserve Dubai’s desert and improve the life of its inhabitants? Why should the Middle East need its own Disneyland and why are we still learning from Las Vegas?

Shouldn’t Dubai — with all the intelligence and imagination and money it has already put forth — continue to become an example by developing new models for it and for the world instead of adopting already failed ones? Shouldn’t these new concepts grow from the dryness, heat, humidity and beauty of its desert?

Moving from the desert of Las Vegas to that of Arcosanti, Dubai could develop a new “zero sprawl” model and out-new the new urbanists. Dubai’s obsession with skyscrapers would finally be put to good use, building vertical density everywhere. Its suburbs would implode. Learning form the Palm’s ripples, entire neighborhoods would be compressed vertically, minimizing their impact on the ground while maximizing the effectiveness of their shared services.

The concept of islands would be transformed from “working,” “living,” or “playing” to “sustainable” and “self sufficient,” each one collecting its own water and treating its own trash. Dubai’s snubbing of infrastructure could lead it to drop infrastructure altogether. Going wireless in this new era, it could go carless as well — no more traffic, highways or pollution, only public blimps and private carpets powered by wind engines moving from one independent living hub to another. Building on its tradition of wind towers, Dubai would thicken the skins of its tower facades to become deep pockets of shadow and cool. It would abandon its love of bland horizontal lawns and adopt the wild organisms of living machines to constantly recycle the waters of its towers.

The new Dubai would concentrate on the “real” as an expression of what is in Dubai perhaps the ultimate fantasy. You live in a desert but with hundreds of thousands of urbanites; you have shrinking oil supplies but inexhaustible sunlight and wind; the focus on density in a small area has given you a city that can be completely traversed by bicycle in less than an hour. What if reality was more interesting than fantasy? Isn’t that what reality TV is proving? To move forward, Dubai should embrace the desert with skyscrapers of adobe, celebrate modernity through advances in sustainability and instead of pretending that the wavy glass of the glorified office parks and the thin-skinned plastic towers that line Sheikh Zayed Road are actually models of anything that can last, celebrate the fact that there is a pleasure in building Babelesque edifices but this time building them right: In Dubai you can always Google a translation…

Work Architecture Company (WORKac) was founded in 2003 by Dan Wood and Amale Andraos. Dan Wood is originally from Rhode Island and has lived and worked in Paris and the Netherlands. He received his BA at the University of Pennsylvania and his Masters from Columbia University. Prior to forming WORKac, Mr. Wood established an international reputation as Rem Koolhaas’s partner in the Office for Metropolitan Architecture (OMA). Amale Andraos was born in Beirut, Lebanon. She has lived in Saudi Arabia, Paris, the Netherlands and Canada, where she received her B. Arch at McGill University. After completing her Masters at Harvard University, Ms. Andraos moved to the Netherlands in 1999 to work as a principal designer with OMA and then to OMA’s New York office in 2002. Both partners currently teach at Princeton University School of Architecture. WORKac’s projects have been featured in exhibitions at the New York AIA Architecture Center, Princeton University’s School of Architecture gallery, the University of Texas’ Goldsmith Hall Gallery and McGill University in Montreal. WORKac has presented their projects in lectures at Columbia and Harvard, and in Copenhagen, Paris, Beirut, Providence, Montreal, and Austin. WORKac’s projects have been published in the New York Times, the New York Sun, Interior Design, Architecture Magazine, A+U Architecture and Urbanism, the AIA Oculus, and 30-60-90.

In Conversation with Farshid Moussavi

Foreign Office Architects, London

Antonia Carver: FOA came to mind immediately when we were planning this feature, partly because of the innovative nature of your work, and partly because of your concept of “foreignness.” I’ve heard you previously describe your practice as “based in foreignness” and “alienation” as a “creative moment.” For me, this chimes well with both Bidoun and Dubai. Could you explain how these concepts affect the way you work?

Farshid Moussavi: The way we mean “foreignness” is less to do with where we’re from, although we both happen to be working outside our home countries, and more to do with a theoretical idea about exteriority as a condition — a proposition for an attitude towards practice that you could adopt even if you were working in your homeland. We think that when faced with a problem, if you stand outside the problem, you see possibilities that you wouldn’t otherwise have seen. It’s possible to release yourself from the local constraints — although you do have to meet those local constraints for the project to be realized. At the level of strategy, the proposition says “let’s stand back and take a broader perspective.” It’s about creating a certain critical distance.

AC: So it’s about balancing internal (practice-led) and external (local) agendas? I feel that in Dubai, partly because the city is so new, the desert seen as so “limitless,” and there’s a supposed lack of a definitive architectural history or style, many architects have allowed their internal agenda to dominate, rather than attempting to embed themselves locally. I’m interested in the way you’ve spoken about contextualizing yourself as an architect, about attempting to “become local.”

FM: We try to think uniquely for every project, because we want to use practice in new locations as a way of constructing identity in our own practice. How is it possible to construct identity for a practice that works internationally? What is consistent and how do you develop consistency when faced with very different conditions, and when you don’t want to become repetitious in your practice? So we use different locations to develop our own practice. Dubai is very new but every site has its own specifics: Some require top-down strategy, in which the architect can impose their vision, others require the architect to generate a concept out of the interiority of the project.

AC: Could we talk a little about the Florence highspeed railway complex? We’re including the project here as an example of the kind of development that could be envisioned for Dubai. I’m interested in the way you’ve taken the station underground and created a park space above, yet connected the station to the city via the eye-shaped viewing holes. Would designing for a rapidly urbanized city like Dubai require different thinking than a European center like Florence?

FM: The way we relate to the idea of travel is common to all of us, so there are some aspects of a contemporary railway station that would be common, whether building in Dubai or Florence. Travel is part of everyday life — yet it’s become something symbolic, something disconnected from everyday life. Most European cities are digging underground and thus liberating ground above, creating new relationships between the city and the railway station. There’s a possibility in Dubai to create real contextual, physical relationships between the railway and the city — after all, a project like this is a huge structure that can radically affect the city.

In Florence, the competition was won by Norman Foster and while I have great respect for his work, it does seem to be a lost opportunity. The glass vaulted roof they are building has lost the project the opportunity of constructing public space on the ground. There’s no point in recreating a Victorian-type shed. Embarking on a new station or railway is about building efficient ways to conduct flows and taking the opportunity to reconnect areas of the city that have been disconnected for years.

AC: As we discussed before, Dubai is in desperate need of a public cultural center, hence us including renderings of your design for the new Centre Pompidou Metz, France [unbuilt]. What was the thinking behind the project and how might it relate to a city like Dubai?

FM: Our design for Metz was a response to the previous Pompidou, where the rooms are hyper-specialized, and initiated in some ways by the brief. We needed to tailor the new museum to different kinds of art, to have it as flexible as possible, and compose different room conditions. The Pompidou in Paris is an icon but works of art are exhibited, rather than interacting with the city. For Metz, we designed a building that had the city as a backdrop from every room. Every space frames the city, and there’s a constant filtering in of views and natural light — so the building brings in public circulation. The inspiration was the [free] museums of London, which are so incredibly public. In the US, museums are very much a commercial experience, but if you take a building like Tate Modern, on weekends it is like a European piazza! This condition was the inspiration for turning the museum into a public space.

AC: It seems to be a project that particularly relates to Dubai: The flexibility, the way it pays homage to the city, and attempts to draw people in — and also the openness and the way escalators are used to transport people between floors gives it some relationship to the shopping mall tradition…

FM: Yes, the escalators and other aspects of the building could be related to a shopping mall — after all, are people in the mall to shop, or to interact with other people? Escalators between the floors offer an extended length of time to interact visually and physically with other people, to create public exchange.

AC: I know you haven’t been to Dubai yet, but could you tell me about your impressions of the city from afar, and from its status and reputation in the international architectural community?

FM: I do admire Dubai — after all, the city has managed to use architecture to give itself a huge presence, not only in the Arab world but internationally. I heard the other day for example that Switzerland’s largest export is architecture. There’s a parallel case in Dubai where architecture has played such a fundamental role in creating an identity for a place. It’s visionary. But at the same time, there comes a time when various visions need to be brought together to create consistency within the urban structure. It’s not dissimilar to China and Korea, where there was an initial, uncontrolled rapid growth, but these places do slow down and realize that they have a mass of building but that they now need to take care in what they do next. From our discussion, it seems that Dubai is maybe now at this stage and that this project is part of the process of taking stock and reflecting on where it’s at.

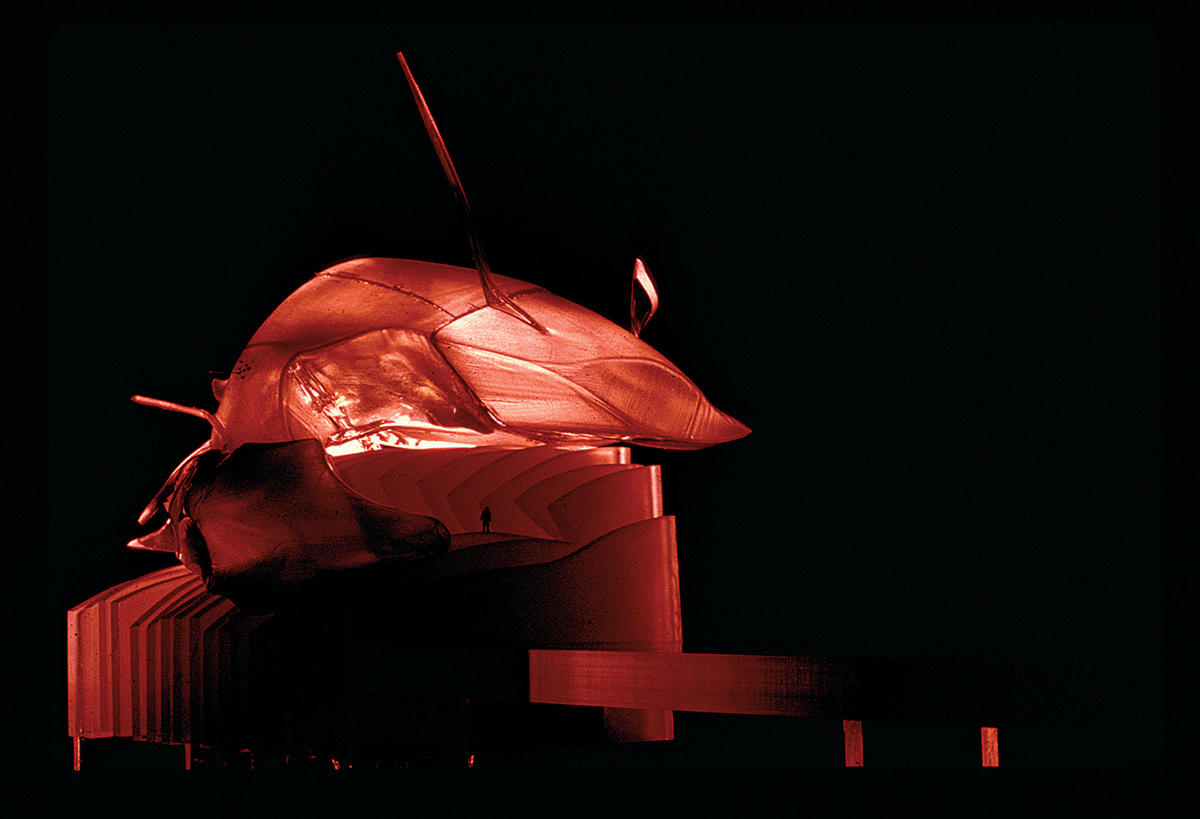

No one sees the world quite like Foreign Office Architects. Their architecture lifts flaps of skin from the ground and mutates them in contorted twists, like plastic surgery for the earth’s surface.

—Design Museum, London

Established in 1993 by Farshid Moussavi and Alejandro Zaera Polo, Foreign Office Architects (FOA) is a London based international practice with a branch in Barcelona. While their work is highly sculptural and evocative, their designs emerge from a rigorous analysis of the brief and functional program.

FOA is best known for its award winning Yokohama Ferry Terminal in Japan, which combines landscaped public areas, conference and cruise liner facilities. Other built projects include the Bluemoon Hotel in Groningen, a Police Headquarters in La Villajoyosa, Spain and a park with outdoor auditoriums in Barcelona. The practice is also working on a number of recent major commissions, including large-scale office developments in Spain and the Netherlands; a Technology Transfer Centre and Social Housing in Spain; the master plan design for the Lower Lea Valley and the London 2012 Olympics Bid; and a new music center for the BBC in London.

The practice was shortlisted for the design of the new World Trade Centre in New York as well as the design of a new Pompidou Centre in France.

FOA represented Britain at the 8th Venice Architecture Biennale (2002) and a retrospective of their work was held at the ICA, London in 2003. Zaera Polo is dean of the Berlage Institute in Rotterdam, while Moussavi heads the Institute of Architecture and is a professor at the Academy of Fine Arts, Vienna.

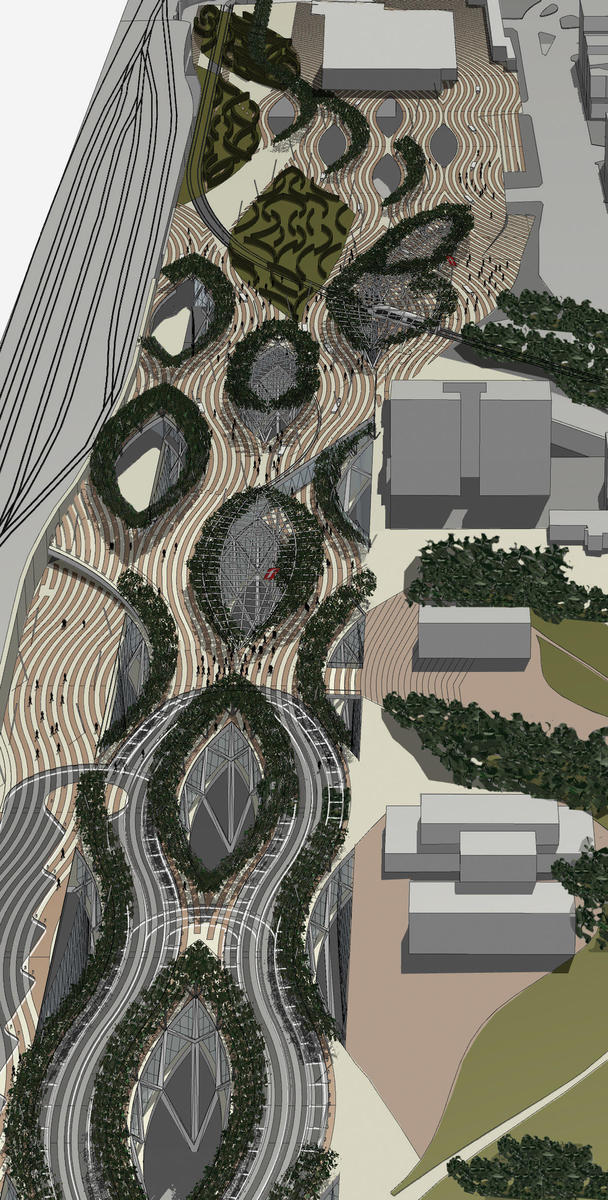

Dubai Culture Hubs

George Katodrytis and Khalid Al Najjar, Dubai

Transformation is a crucial element of contemporary urban culture. To cope with the demands of society, cities are constantly in flux. They grow both vertically and horizontally, increasing in density and intensity. They require restructuring and transformation on almost every level. Our proposal focuses on the manipulation of the urban fabric by inserting structures that trigger change, provoke and demand response.

The proposal is for a series of cultural hubs, which will act as focal points and public foyers where cultural programs can be plugged in: art galleries, museums, libraries, performance stages, poetry reading salons, music recital spaces, art auction facilities, etc. The main lobby of the buildings is to be as public and accessible as possible, like a typical Dubai shopping center, with escalators and ramps leading to the upper levels, and to special rooms for additional cultural events. All events and items will be consumable: the aim is to convert the culture of shopping into shopping for culture. The external skin structure and glazing is designed using algorithmic weaving scripts.

George Katodrytis is an Assistant Professor of Architecture at the American University of Sharjah, UAE, and a consulting architect in Dubai. Previously, he taught at the Architectural Association and the Bartlett in London, and has lectured and exhibited worldwide. He has built offices, residences and residential conversions, corporate interiors and exhibitions in the UK and Cyprus, as well as contributing proposals for developments in the UAE.

Khalid Al Najjar studied at Columbia University, New York, and the Southern California Institute of Architecture, before moving back to his hometown, Dubai, and setting up dxbLAB in 2000. The firm has since been recognized as one of the most innovative in the region, recently winning the Best Design award in the Mohammad Bin Rashid Awards for Young Business Leaders.

Recognizing a common aesthetic, George and Khalid began working together on invited competitions and other proposals in Dubai in 2003. Projects are developed from a strong initial concept to a complete exploration of program and form, characterized by innovation.

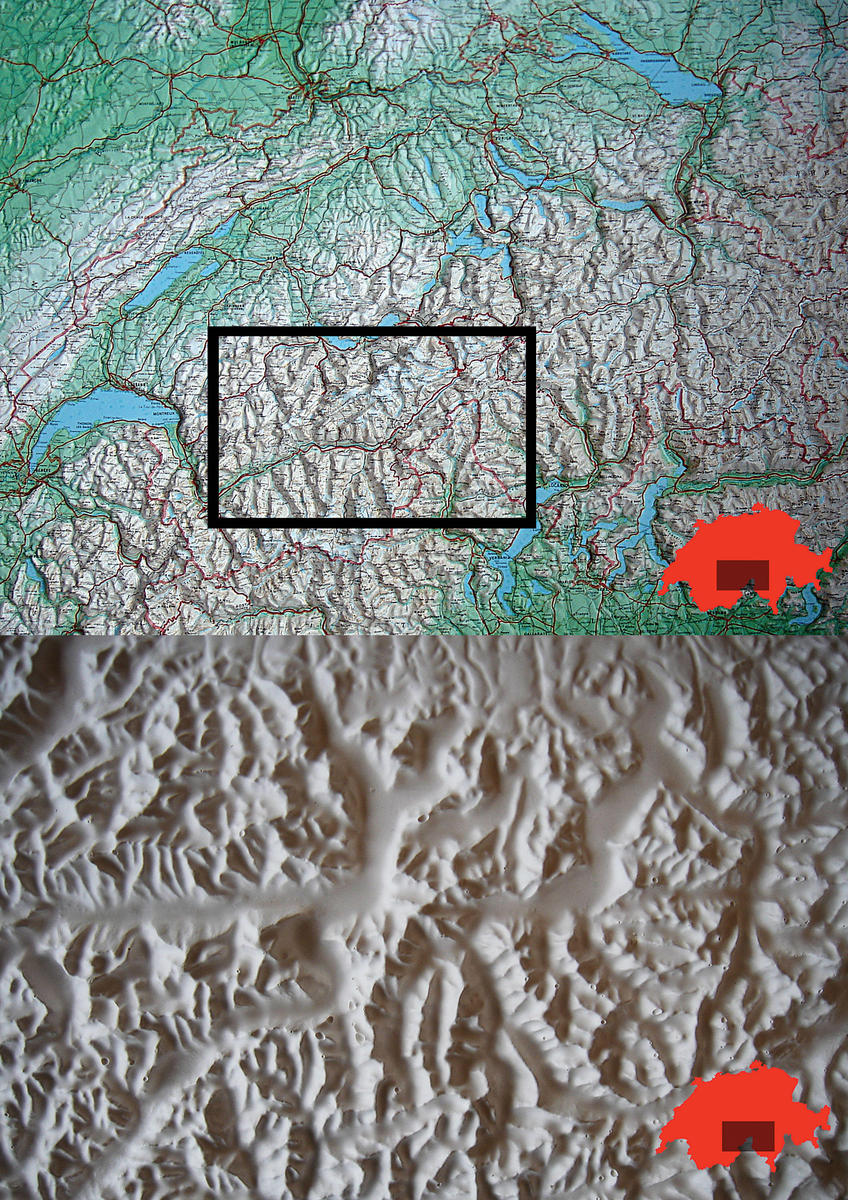

Teconic Logos

Group8, Geneva

Founded in 2000, Group8 is an architectural practice composed of nine partners, 16 employees, and two permanent consultants. They have recently won two important competitions: The “Maison Verte” that will house the regional administrative offices for sustainable development and the International competition for the extension of the WTO. They are research oriented with four of the partners involved in teaching at the architectural Institute of Geneva (IAUG), at the polytechnic school of Lausanne (EPFL) and as invited professor in the School of Applied Arts in Geneva. Group8 is not concerned with style or recognition through style. Group8 believes that architecture a never-ending work in progress.