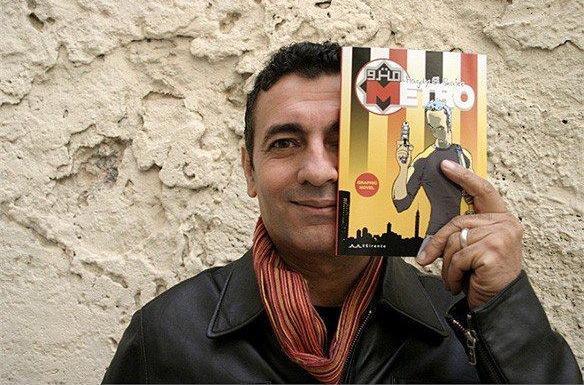

Metro

By Magdy El Shafee

Dar Malamih, 2008

Arabic

“Today I decided to rob a bank.” With these words, Magdy El Shafee’s graphic novel, recently out from Dar Malamih Press and believed to be the first Egyptian work of its genre, opens. The work revolves around Shihab, a computer engineer specializing in electronic security systems for banks and businesses. Shihab’s small firm has suffered huge losses and gone bankrupt because of corruption and big business market domination. While planning to rob a bank, he accidentally turns up evidence that implicates corrupt businessmen in embezzlement and finds himself pursued by them and by the police after the former have accused him of a murder he didn’t commit. So it goes in the cruel world of Metro.

El Shafee’s novel is divided into chapters, each of which bears the name of a station (itself named after a former president of Egypt) on Cairo’s underground rail network. In moving from one metro station to another, the author provides a survey of Cairo’s various contrasting quarters, starting with the slums of El Marg, Guiza, and Feisal and ending with downtown Cairo’s belle époque quarter. Similarly, the author uses the metro to move Shihab between two worlds — that of marginalized Egyptians (embodied in the person of Uncle Wannas, the shoeshine man) underground, and the aboveground businessmen who supervise the stealing of elections. Recent Egyptian political events, in the form of demonstrations, elections, and torture at the hands of officials, comprise the backdrop. By the end of the novel, Shihab has discovered that everyone lives in a mousetrap and, though the trap is open, people are too afraid to leave it. Shihab chooses to leave the mousetrap and abandon any respect for the law, which he sees as no more than a means for the strong to dupe and dominate the weak. No sooner, however, has Shihab gotten out of his personal trap than he discovers that there are other escapees who are even more frightened than those still inside.

The political thread in Metro is one that has begun to emerge in a number of Egyptian literary works written in recent years, largely as a result of the country’s political ferment. What distinguishes Metro from other works, however, is the author’s choice of the graphic novel, a medium new to Egypt’s creative arena, to express his preoccupation with this reality. This choice reflects the opposition’s efforts to find new artistic forms for presenting its positions. The author does not focus exclusively on marginalized classes to illustrate the impact of corruption on the country — in contrast to most Egyptian works dealing with the political situation from a leftist perspective, which views the conflict as simply taking place between the oppressed and the oppressor, the good and the bad. The author concentrates on characters from the middle class, whom he attempts to portray as human rather than angelic. Thus Mustafa, Shihab’s friend, does not, at the end of the novel, stand by his friend, but takes the money they have stolen from the bank and escapes abroad with it, leaving Shihab behind. Similarly, the novel refuses to offer a solution pleasing to all parties, or to allow good to triumph over evil. Shihab merely satisfies himself with embracing his girlfriend in the metro station while life aboveground continues at its normal pace.

The same atmosphere is reflected in the language in which the author chose to write his novel. Since images carry the story, words only had to express dialogue. El Shafee eschewed obscure and standard formal language, instead depending mostly on colloquial Egyptian to lend realism to his characters and to generate satire. He also refused to exercise any form of censorship over his writing; The novel contains a number of expressions that some may find unacceptable or obscene, but the author views these as ordinary expressions that we hear almost every day. His use of these expressions presents a panorama of Egyptian realities: crowding, hiring thugs to influence elections, economic slowdown, unemployment, Muhammad Abu Treika (darling and role model of the poor), cellphone ringtones, etcetera.

Magdy El Shafee’s illustrations are entirely in black and white and employ a line intentionally chaotic and interwoven in order to evoke for the reader a sense of the chaos of Cairo’s streets. The most corrupt characters in the novel have faces that are drawn from real life, faces constantly seen on television and in the press, and the same is true of those characters who struggle for a better society and fight corruption. In this way, Metro reflects reality not only on political but on social and cultural levels. This aspect of the work is embodied in the character of Dina, Shihab’s sweetheart, an idealist who takes part in demonstrations in hopes of transforming not only the political but also the social reality. She is determined, for example, to keep her relationship with Shihab outside the standard Egyptian social framework of marriage. El Shafee uses this relationship to provide his novel with a romantic dimension and, at one point, to present a scene of frank eroticism between Shihab and Dina — this at a time when the professors at Cairo University’s Fine Arts Department are clothing the nude statues used by students learning to depict the human body.

Unfortunately, Metro’s realism is more than Egyptian officials could stand. This April, shortly after Metro’s publisher Mohamed Sharkawy was arrested for advocating on behalf of workers, the press’s offices were raided by the vice squad. (Sharkawy, incidentally, has been a much- publicized victim of torture at the hands of authorities in the past.) All copies of Metro on hand were confiscated. Since then, Sharkawy and El Shafee have been charged with “offending public morality.” And, as ever in Egypt, people must negotiate the black market to find their way to this timely text.