Impasse was screened in June of 2024 as part of Bidoun’s ongoing film program at Anthology Film Archives, New York.

In the fall of 2022, as the largest uprising against the Iranian government in decades raged in the streets of cities across the country, Rahmaneh Rabani began filming the conversations she was having with her parents and siblings. Over the course of fifty-two days, she shot interviews, arguments, prayers, parties, and road trips. Now this footage has become Impasse (2024), an energetic and keenly observed documentary portrait of family relationships, religious faith, and the internal workings of what might be described as patriarchy, Iranian style. The film, which Rabani wrote, directed, and produced with Bahman Kiarostami (who also served as its editor), speaks to a dramatic moment in Iranian history from the front lines of its ideological divides.

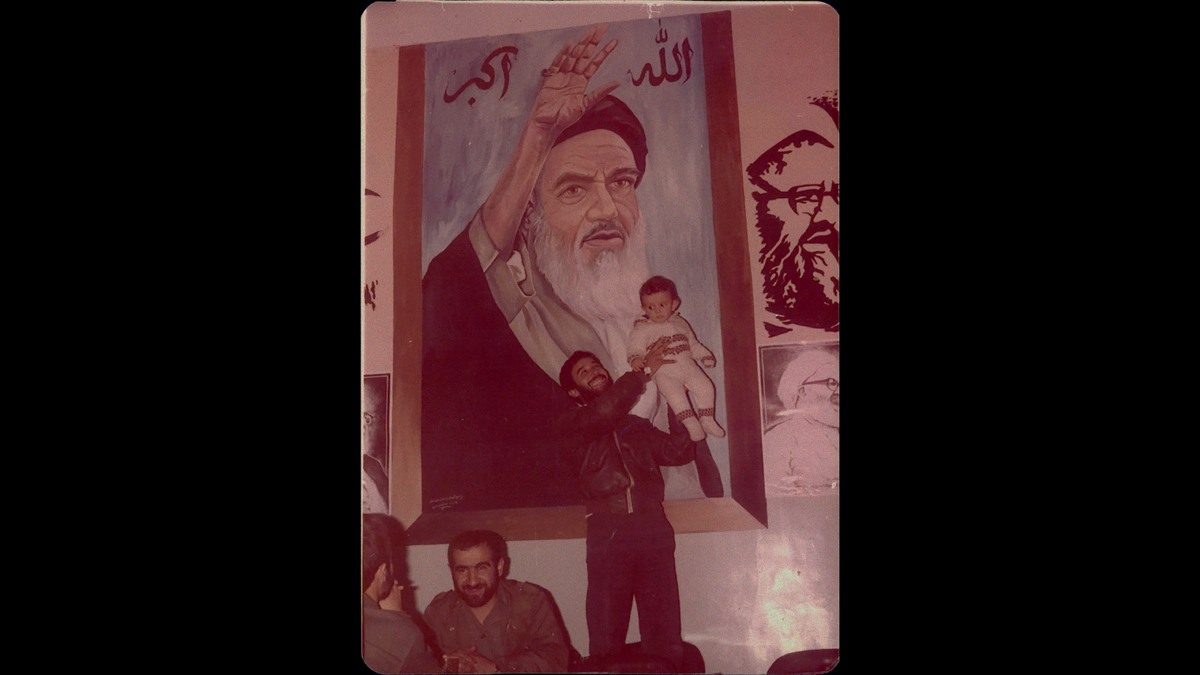

Impasse is a chatty documentary, its dialogue occasionally scripted but more often captured impromptu. We meet the characters through Rabani’s first-person voiceover. “I’m Rahmaneh. They call me Rahi. Raastin’s mother. Daughter of Haj Akbar and Elaheh. Sister of Sadegh and Fatemeh and Hossein.” This is followed by a series of informal interviews with the family members, their backstories supplied through expertly spliced photos and home movies. The protests transpiring outside insinuate themselves into the intimate conversations of the Rabani home as Rahi’s camera — and her persistent questioning — threaten to tear her family apart.

Early on, Impasse sets the scene: “In September 2022, after the death of Mahsa Amini, the twenty-two-year-old Kurdish girl who was arrested on a visit to Tehran by the Guidance Police for ‘improper hijab,’ and died under suspicious circumstances a few hours later, protests emerged against mandatory veiling, and women and men, young and old, came to the streets.” We see handheld footage of unveiled women marching, swinging their headscarves above their heads, openly defying the Islamic Republic’s dress codes. “That’s when I decided to reopen an old debate with my family.”

“Hijab has always been a source of disagreement with my family. Until the age of twenty-two, I was just like the rest of my family, a believer and fully veiled,” Rahi explains, over clips of a younger, chador-clad, shyly smiling self. “But it’s been nearly fifteen years since I chose to follow my own path.” We see her unveiled, at home and on the streets; we learn that she has been to protests, including one where she was attacked by the police. (“My wife was hit in the butt by a baton and her iPhone broke,” her husband notes.) When her two-year-old son Raastin starts imitating the chants of “death to the dictator” that he hears outside, everyone is concerned except Rahi, who insists it’s no big deal. But Rahi knows she is playing with fire.

An impasse is a deadlock, a situation that makes it feel impossible to move forward or walk away. But in Persian — where “ampass” is a direct loanword from French — one is most often “placed at an impasse” because of someone else’s actions. In Impasse, the deadlock in question is between the freethinking Rahi and her deeply religious father, Ali Akbar. Haj Akbar, as he is known, is a war veteran and an unwavering supporter of mandatory veiling. We meet him in his wood-paneled living room, a white-haired, trimly bearded man who keeps an eye on the nightly news amidst a comfortable jumble of plush couches, ornate carpets, well-tended houseplants, and visiting family.

Akbar’s impasse is not, to his mind, his religious debate with his daughter. It’s her insistence that it be filmed. “I wish you wouldn’t do this,” he says in an early scene, pointing to the lens. “I wish you would just sit down and talk to me.” Though he claims that he is not afraid of “evidence,” Akbar has watched enough TV to know that any stumble, foible, or loss of control may be used against him, especially by his rebellious filmmaker daughter. It’s not just that, though. The camera’s mere presence in his home disturbs the balance of power that should be his, unquestioned — his fatherly birthright under patriarchy.

“When they say it’s hijab, it’s not just about hijab,” Akbar lectures a granddaughter one evening. The girl, Nargess, wears a peach-colored headscarf with matching pink glasses. She sits facing her grandfather, fidgeting as he warns of the dangerous slope, so slippery, that would result from giving in to the protesters’ demands. “They keep introducing new things,” he continues. “They force their material temptations and sexual temptations and personal views on others.” A portly uncle, stretched out on a couch nearby, smiles bashfully at the camera; another laughs silently as Akbar drones on.

Elaheh, Rahi’s mother, is a generally sunny woman who pins her scarf under her chin like an old-school TV presenter. She has kind eyes and an easy smile, projecting equanimity and reasonableness even as she enumerates her daughter’s failings as a mother. (Her grandson’s bowel movements or lack thereof are a recurring theme.) Elaheh’s commentary can be as dismissive as her husband’s, but her delivery has the air of a natural comedian. “You ruined your own future,” she tells Rahi, eyes flashing. “I didn’t want to be a doctor or an engineer,” Rahi shoots back. “I wanted to be an artist,” she says, using the English word.

R: Do you know what “artist’ means?

E: Yeah, I know. It means actor.

R: No, Mom. Artist, not actor.

E: Artist. I don’t like it at all, this job —

R: Mom! I like it

E: —not at all! All the lazy people, the shameless people, they’re all artists. All the people who want to show off. I can’t bear actors.

R: Mom! Artists.

Rahi is a cheerful, generous interlocutor, who takes her family’s criticisms in stride. She refers to her parents by their first names and teases them often. She films Akbar leafing through his wartime photo albums, and hoots with laughter when he admits that his war wounds were not combat-related, but the result of a car accident. “I’m never going to hear the end of this,” Akbar sighs, half-smiling.

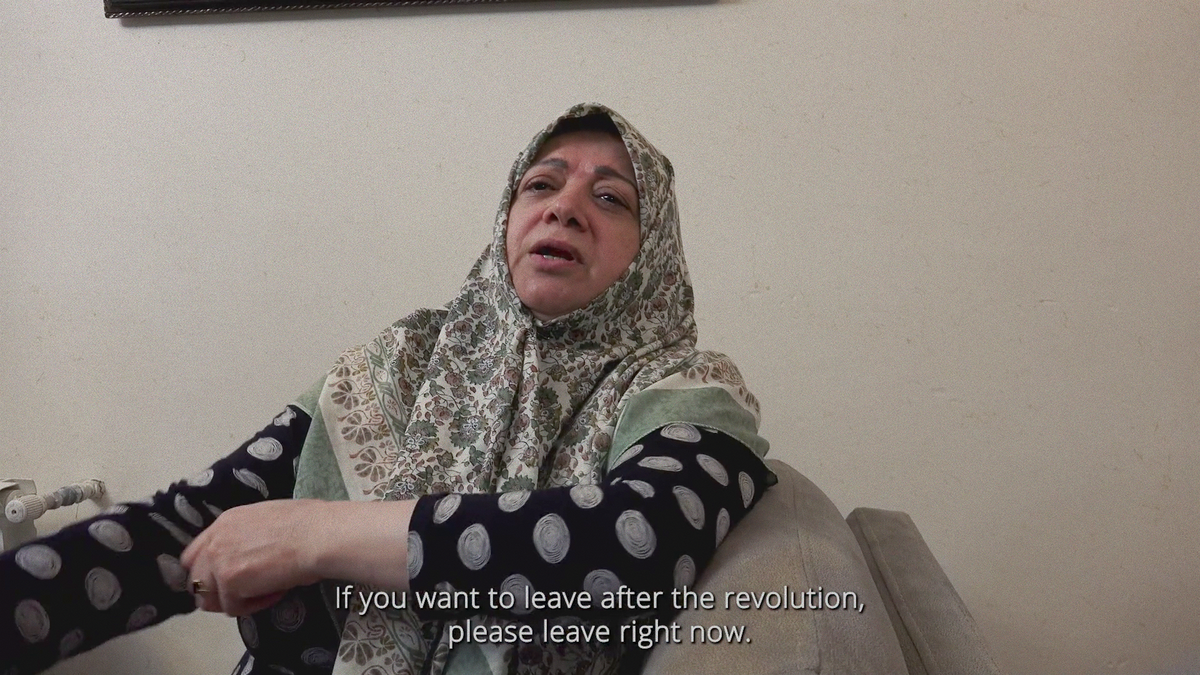

With each family member that Rahi interviews, her impasse takes on a different refraction. Her elder sister Fatemeh is a solid supporter of the status quo; she worries about innocent people beaten, chadors torn off heads by force, the arrival of end times. “There’s no way around it, we’re living in an Islamic country,” she says with finality. Rahi’s younger brother Hossein, a former seminarian, thinks she should simply accept the Faustian bargain she’s made: “You were born into a family where you have to wear the chador, and you don’t, and you’re paying for it. That’s how it works. You have to pay for things in this life.” Her older brother Sadegh is a freethinker: he believes it’s not women’s bodies that should be policed, but men’s gazes. But he sees their father’s side of it: “He wants us to be the way he raised us.” As it happens, it is Elaheh who offers the most controversial take: “People who’ve been in a war zone, they aren’t healthy people,” she tells Rahi in a low, conspiratorial tone. “What do you expect from a crazy person?”

Near the end of the film, Akbar turns the tables on his daughter, requesting that she point the camera at herself, “the one who needs to answer,” and she submits. “Could you define God for me?” he begins, his hands the only part of him visible in the frame. “Or, you said you don’t believe in the teachings. What is it you don’t believe in?” Akbar wants to get away from the specifics of her complaint about hijab and discuss first principles. His home ground. Rahi sits, dejected, a look of palpable exhaustion on her face as he pecks away at her, enumerating the teachings she has rejected, her failures to conform to the righteous path. When she dares to suggest that a nonbeliever could still live a virtuous life, he is condescending: “So you want me to become a follower of your beliefs?”

R: No, not at all. Not at all. All I want, all I want from you two is to accept me as a human being with human values. Don’t keep telling me I’m worthless because I don’t look the way you want. Don’t overlook my value, my whole being, my beliefs, all the love inside me, just because of some formula…

A: So what am I supposed to do now?

R: Accept me. See me. See my worth. If you think I’m worthless, just tell me that. Not because my wrist is showing or my hair…

A: You won’t do what I say, so there’s no point in seeing anything else… I have nothing to say to you. I just want to tell you to be human.

R: Am I not human?…

A: I don’t know, that’s your business.

Tearfully, Rahi announces that this is why she is filming these conversations: “Because I’ve been attacked my whole life.” She wants to be able to show them to her child when he is older, so that he can understand. This is her impasse.

There is a fascinating resonance between Impasse and Leech, a 2021 film by Rabani’s collaborator Bahman Kiarostami. Leech is a documentary short that presents a trio of previously recorded conversations between Bahman and his father, the acclaimed artist and film director Abbas Kiarostami, between 1990 and 2002. “Conversation” is not quite right; each scene depicts an interrogation. The second one, recorded in 1994, when Bahman is fifteen and already a budding filmmaker, is especially harsh. “Why have you failed to study for a whole year?” Abbas asks his son, who is flunking nearly all his classes at school. “Why?” Abbas remains off-camera, his son’s sullen stoicism unfazed despite his father’s increasingly strident vituperations. “As a human being, what do you have to say for yourself?… You’ve been given everything, but you do nothing in return. Why?!” In one notably unhinged reverie, the elder Kiarostami ventriloquizes his son: “Camera! I want to live like a parasite, like a leech!” (It is somewhat shocking to hear the illustrious filmmaker, famous for making tender, attentive films with and about children, address his own child this way.) In the final segment, from 2002, when the son, now an adult of twenty-three, confronts his father with the earlier footage, Abbas is unrepentant. “There was a Bahman, the boy whose photo is on the piano, I knew that kid once. He was a wise kid. I learned a lot from him. But that boy died at twelve. That boy turned into something I don’t understand at all.”

Both Leech and Impasse foreground the experiences of a child contending with a parent locked blindly into their own anxieties. But where Leech is almost painfully claustrophobic, its fixed camera trained tightly on Bahman’s face, Impasse is fluid and open-ended, switching easily between conversations and their settings. The camera’s curiosity lends the film a tantalizing immediacy, as Rahi’s interrogations expand to register, say, a running toddler, an in-law doing calisthenics, or a clutch of nieces in varying shades of hijab. Impasse is a remarkable feat of editing, too, stitching together an improbably tight and propulsive narrative that, while evoking the meandering chaos of everyday life, manages to organize it into an engaging and substantive whole. While it is possible, perhaps inevitable, to see the film as a metonym of Iran’s gaping ideological rifts, Impasse is, above all, a panoramic presentation of a divided but deeply committed family.

Impasse’s most unguarded interviews are with her three young nieces, whose experiences and opinions provide a measure of hope. Yas, a pop music-loving teenager, has trouble imagining a Muslim whose faith does not entail the veil but believes that society has room for nonbelievers. “We have to live side by side,” she says confidently. “Isn’t that what it it’s like all over the world? What can’t it be like that here?”

Saba, a preternaturally calm preteen in a knitted black headscarf, reveals herself to be a rebel in Rahi’s mold. “I told my mom the other day, I told everyone, I don’t believe in hijab. And my mom said ‘okay, but when you come out with me, please wear it…’ and I said okay. But she knows that if I go out alone, I won’t wear the hijab.” After the interview, the camera follows her as she pulls off her scarf with a demonstrative sigh. Rahi, who has perhaps only now learned Saba’s stance on the issue, apologizes for asking her to wear one, but Saba shrugs. “It’s okay,” she says, “and it was cold outside, anyway.”

I’m inclined to give the last word to young Nargess, last seen enduring Akbar’s lecture on temptation, who positively cannot wait to address the camera. She has a bouncy, impish energy, a wide, gap-toothed smile, and — once she gets going — very decisive opinions:

Well… My opinion is, it’s better if people accept that some people can decide to be hijab-less. But they should know — if they go to hell, it’s on them. But we shouldn’t do anything to them. The hell with them. They’ll go to hell. [She grins and waves her hands to dismiss the imaginary masses.] And good for those who wear hijab. But when people protest, like, “Why aren’t you wearing hijab” or “Why do you wear hijab”? That’s stupid. [She sits up, indignant.] And the police keep showing up [mimics an imaginary policeman counting misdeeds on his fingers] like, “You shouldn’t be on the street, you shouldn’t be hijabless…” Come on! Let them go. Let them go to hell. It’s none of your business.

She leans back, satisfied. “So that’s my opinion. Let them be.”