For those of us who’ve had the opportunity to stomp all over Marwan Rechmaoui’s Beirut Caoutchouc — a map of the city made of interlocking slabs of tough black rubber, spread across the floor like an oversized industrial slipmat — there may be another layer of urban experience to contend with in the near future. Rechmaoui, whose working process is famously methodical and notoriously slow, is about midway through a sequel of sorts, a new piece called Blazon.

The first piece, which was produced by Ashkal Alwan for the 2003 edition of the Home Works Forum, represents the most basic geography of the Lebanese capital. The artist cut the city into segments corresponding to the many municipal sectors of Beirut that snap together in the manner of a large-scale jigsaw puzzle (when installed, Beirut Caoutchouc measures roughly eight meters by seven). Carved into the surface are the shallow grooves of highways, streets, and alleyways, all of which are otherwise unmarked. While the map is accurate, it downplays well-known divisions. There are no indications of the different political or religious identities that characterize certain neighborhoods. The green line that splits the city in two appears as just one unremarkable line among many.

Beirut Caoutchouc plays with the myth and melodrama of Beirut’s resilience, a city that has bounced back countless times after being wrecked by earthquake, fire, and war. But by reducing Beirut to a flat, commonplace material — and by inviting people to walk across it, find their place on it, or trace there the routines of their days — it raises questions as to how the city has come to be known and experienced. The piece encourages viewers to consider the strange shape of the city and its development over time: how the port and quarantine grounds were added onto the historic core; how sleepy suburbs became urban sprawl; how Armenian, Palestinian, and Iraqi refugees moved in and settled down; how a massive rubbish dump became reclaimed land slated for the future development of parks and skyscrapers. It does so more effectively than any normal map because it presents Beirut as an object rather than an image.

Rechmaoui has described Beirut Caoutchouc as a piece about the singular division of Beirut, which persisted as an idea in the aftermath of Lebanon’s fifteen-year period of civil war. Considering the city now, he finds it more fractured and factionalized than before, suggesting that the civil war never truly ended and was never just one war to begin with, but many and competing wars. Blazon, then, is his gesture toward representing — and, by extension, investigating — these multiplying cracks and fissures.

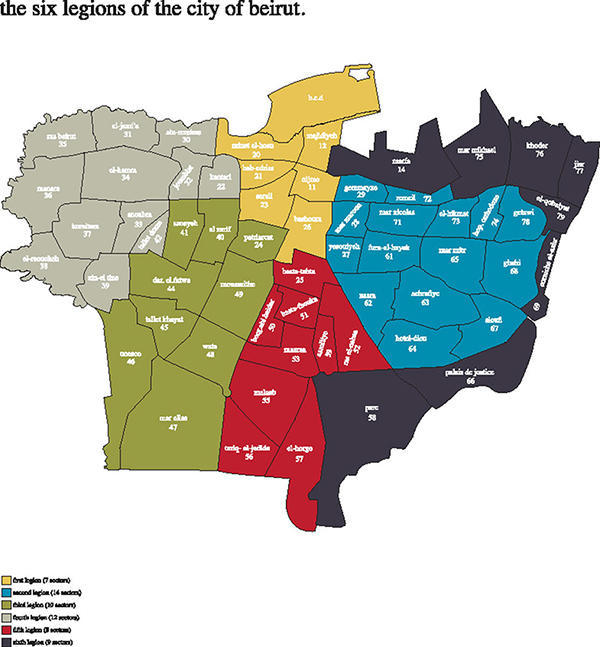

For Blazon, Rechmaoui imagines Beirut as divided into six legions. Each legion corresponds to a version of the city as defined by pivotal moments in history, when borders swelled and expanded in response to wider political conflicts, economic crises, and demographic shifts. Each legion is assigned a color, an insignia, and a shield emblazoned with a coat of arms. The military lingo befits Rechmaoui’s idea of Beirut as a place that is always on alert, always preparing for another war.

As a work in progress, the piece currently consists of numerous graphic images — mostly maps and shields — on Rechmaoui’s laptop. But he plans in the coming months to translate a series of those digital files into large-scale works in vitreous enamel, or industrial-grade stained glass, fusing glass powder and pigment to sheet metal or cast iron in a kiln whose temperature exceeds 800 degrees Celsius.

Rechmaoui recently located a factory specializing in vitreous enamel on the Isle of Wight. The bulk of the factory’s business consists of things like appliances, chip-proof bathtubs, internal cladding for restaurants, and graffiti-resistant signage for the London underground. But it also does less explicitly commercial commissions and, rather unusually, runs an artist-in-residence program as well. Rechmaoui hopes to spend a few months working with the factory, learning about the material and mastering its properties. The industrial use of vitreous enamel is particularly appealing for an artist who typically works with cement and Plexiglas and rubber.

In the context of Beirut’s contemporary art scene, Rechmaoui is something of an aberration. He began his career as a painter, mining abstract expressionist and social realist motifs. Then he started making wooden panels covered with materials such as concrete, tar, iron, and glass. In the late 1990s, he abandoned two-dimensional works altogether and “got off the wall.” All of his works since then have been either sculptural or architectural. He has a deep and long-standing commitment to the spatial configurations that are created by placing three-dimensional objects in a room. He sees the hanging of two-dimensional works on the wall as a significantly less interesting proposition (for Blazon, Rechmaoui is exploring ways to make the glassworks freestanding).

Rechmaoui may share certain aesthetic, conceptual, and political concerns with his peers in Beirut, but while they tend to employ documentary and archival practices that rely heavily on critical texts or artist’s talks to generate meaning, Rechmaoui confronts viewers with no more than form, volume, and space. His work has a tactile presence that is absent from that of his colleagues. He rarely speaks about his work in public. He does not write texts, collect photographs, make videos, or stage performances. He insists that his objects — large, labor-intensive things crafted by hand or in factories — speak for themselves.

He is also far from prolific. He’s completed just four pieces in the last decade: Beirut Caoutchouc, Untitled 22 (a map of the countries that make up the Arab League, each placed at a slight distance from one another), Monument for the Living (a concrete replica of Burj al-Murr, a dysfunctional high-rise in downtown Beirut that is, for many, an appropriate memorial to the stupidity of war), and Spectre (also a concrete replica, this time of the Yacoubian Building in Ras Beirut, which Rechmaoui uses as a brilliantly understated case study for the failures of modernity).

Though Rechmaoui’s practice involves considerable research, preliminary sketches and plans, and multiple experiments with different materials, he rarely shows any of the background matter that influences his thinking or feeds into the creation of a final piece. Except for occasional illustrations in print publications, he has preferred to make and remake only those four pieces, often in slightly different versions or after intervals of many years, as new occasions for exhibition (or acquisition) arise.

Such is the significance, therefore, of Blazon, which is already, at the time of this writing, four years in the making. It also signifies a subtle shift in Rechmaoui’s approach to Beirut, which has always been, not just central to, but everywhere in the artist’s work.

“If I lived in London, I’d work on London, as a space,” he says. “So it’s not Beirut itself but what’s happening in this place. It’s the exchanges and the inheritance of things.” Rechmaoui says that the divisions operative in Beirut now are comparable to those of thirteenth-century Sienna or any moderately globalized city today, racked by competing political ideologies or ethnic tensions or trade in illicit goods and services.

“The whole world is moving in this direction,” he says. “This is why Beirut is important. It’s the future. Populations are moving wholesale into cities, and bringing with them their issues, their problems, which puts pressure on the city as a space. New York is the same, but the expression of it is polite. If you look at drugs or prostitution anywhere, you see the divisions. In some places it’s covered up. Here it’s open. I think there’s no more first world and third world, developed world and developing world. It’s getting messy all over the world. All these issues about security and terrorism mean that Western societies, which believe they are free, are starting to lose the benefits of being free. And if that’s happening, then the whole thing will be turned upside down. Underdeveloped societies will find themselves ahead because they have experience with insecurity and violence. Their immune systems are stronger.

“I’m not saying this is something good. It’s fucked up, but this is how it’s going. It’s a very perverted situation. When I started doing this work, I wanted to figure out why this city is so charming, why it’s so nice, because it’s not nice, but we enjoy it. People come here and think it’s friendly, but it’s full of hate and people killing each other. So what’s wrong here? The idea of friendliness, or the idea of hate? Look at the urban planning of Beirut. It’s totally chaotic, but we think it looks nice. We enjoy it. Does that mean there’s something wrong with me? Or with the idea of urban planning? So I’m trying to understand that. But all what I’m telling you now won’t be in the work. I’m just doing this to get to how those shields will look. Maybe there will be flags, too. When you enter the space [where the final work is installed] you must feel the intensity of a war that is about to start, a war that is just waiting for a spark.”