Lies, crimes, and stereotypes…pulp is the kingdom of the obvious and exaggerated, the sensational and the predictable, peopled by detectives, werewolves, and robot girls. In pulp loves comes in two flavors; saccharine sweet and raunchy porn. Pulp is worth exactly the paper it’s printed on—the cheapest paper in the world.

Pulp means paper; or rather, the mulch from which paper is made. And it is this relationship to the physical that is the key to pulp, as genre and as critique. Pulp can be a painting, but not art. A book, but not literature. A movie…but not cinema.

Pulp is a load of crap.

But then why are we bothering with this shit? Why look at, read, or watch pulp at all? Or at least, why admit it?

Pete Woods, a British connoisseur of five continents’ worth of trash films, provides one answer in his book Mondo Macabro:

Horror films, sex exploiters, and monster movies…are usually avoided by heavyweight histories. Which is odd, because in our encounters with Filipino action heroes, Hong Kong horror stars, and Japanese bondage queens, we’ve learned far more about their respective countries than from any number of serious art films…Genre films…always grow out of their country’s most deeply ingrained traditions. Like crates of oranges with their brightly colored labels, these films are always instantly identifiable.

The allusion to oranges is oddly appropriate. Pulp is everything that gets strained out to make juice. But where pulp ends and juice begins is completely a matter of taste…taste, and the width of your straw.

The suckers with the widest straws are artists. The artist can exploit the rawness of even the most elevated cultural material. Like archivists, they make meaning by selection; like B-movie moguls, they embrace appropriation; and like librarians, they manipulate content through context.

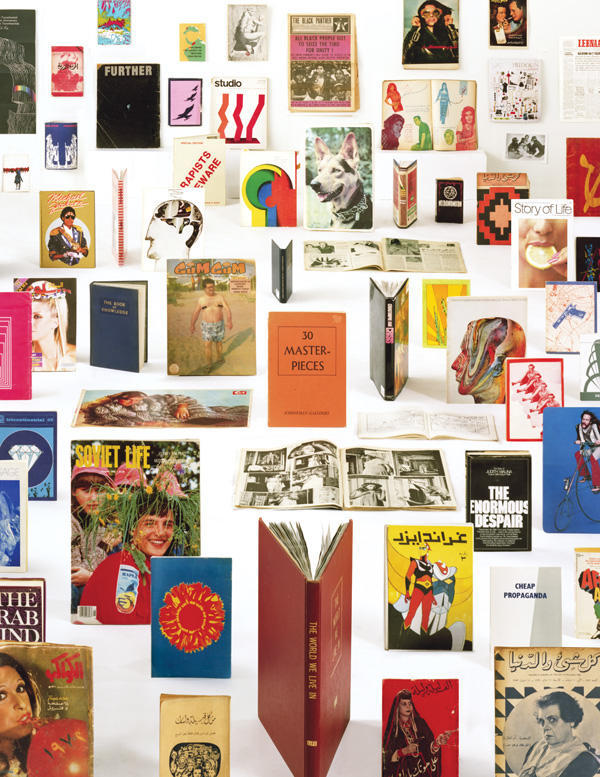

In her project Untitled Polaroids, Haris Epaminonda turns her camera on her private library, photographing photographs from the pages of books; the result is a series of images that reads like a gauzy travelogue of a trip to a vintage encyclopedia. A similar journey is evident in the works of our own Babak Radboy, whose textual still lives are scattered throughout this issue—spoils of his recent excavation of Beirut bookstores, informed by his complete ignorance of Arabic and a keene eye for conspiracy. Ahmet Ötgüt presents a photo-series celebrating a neglected form of national poetry—the rhymes and sayings Turkish truckers splash across the backs of their rigs. Although there’s plenty to ogle, we know you only read Bidoun for the articles… In “Thirty-One Flavors of Death,” Achal Prabhala profiles Omar Ali Khan—ice cream magnate, schlock-horror cineaste, and Pakistan’s unlikeliest cultural tastemaker. Sophia Al-Maria’s “Beauty As the Beast” evokes a pulp pantheon of femme-dom-fatales whose tales are accompanied by portraits from the ejaculatory ballpoint pen of artist Cary Kwok. And Anand Balakrishnan provides a thrilling pastiche of pulp non-non-fictions in his most honest and exaggerated Bidoun treatment yet, “The Toughest Man in Cairo vs the Zionist Vegetable.”

All this, plus beach fashion, a drinking game, and editor Negar Azimi’s intimate evenings with the Iron Sheik. And all of it printed on the thinnest, cheaper paper we could find.

See you,

Lisa Farjam