I was born in Kyrgyzstan. In our Asian culture, there are very strict gender boundaries. Someone born male has to stay a man. Someone born female must stay a woman. This is the idea about gender, and crossing the boundary is considered a sin that must be punished. No one has the right to change what God made.

As far back as I can remember, I felt I was a boy. I’m the second of six children. The head of the household was my grandmother. That turned out to be very important.

My parents are wheat farmers with a few cattle, and we lived in a rural area not far from Bishkek. My father isn’t really religious, but he has his own ideas about how things should be. He’s like most people in Kyrgyzstan — not very Muslim, but still using religion to explain things they don’t understand.

A lot of my relatives assumed my boyish behavior and male dress style would lead to problems in my adult life. And by “problems in my adult life,” I mean homosexuality. They thought I needed to learn to behave as a girl, and they pressured me to wear skirts and dresses. Several times, my aunts and cousins burned my shirts and trousers so I had nothing left to wear but feminine clothes. All I could do was stand in the yard, watching the fire while my older relatives looked on.

Afterward, I always cried and begged my grandma to get me new clothes. I would promise to be good, to get only excellent marks at school, to stay out of trouble. A couple weeks later, my grandma would buy them for me. The rest of my family perceived me as a troublemaker — they called me a hooligan. At least in that sense, I guess it was your typical boyhood.

The older I got, the more pressure my family put on me because of my male expression and style. Finally, my grandma put a stop to it. She told them that I would behave female as an adult, but until then, they had to leave me to my preferences.

I was seven or eight years old when my grandma’s neighbor came to visit. She said that somewhere — maybe in India — there were two girls who loved each other and that one of them had surgery and became a man so they could get married. I was standing near my grandma, and they both turned to me and agreed that since I looked like a boy, they would let me have the surgery. It was a joke for them, of course, and I still have no idea where our neighbor heard this story, but the words stuck in my mind.

When I was fifteen or sixteen years old, I tried hard to change my identity in accordance with my family’s wishes. I put on female clothes and played “normal girl.”

It didn’t work.

I enrolled at Bishkek Humanities University. I was a top student in the sociology program and won the Republic Students’ Olympiad in philosophy. Ancient philosophy — Aristotle and Socrates — was always my favorite, along with Eastern philosophies like Taoism and Confucianism.

I had a girlfriend who lived in my dormitory. Neither of us had heard of the terms transgender or transsexual. My girlfriend looked really feminine, and I looked… different. It wasn’t hard for people to believe we were together.

And that’s why I got kicked out. My roommate wrote a letter to the dean that said I was a faggot and that she was afraid to live with me because I had inversion. The dean summoned me and two of my friends to her office and said, “There is no place for freaks in our university.” We all had to leave. My friends were neither gay nor trans; they were punished just for being supportive of me.

After we were expelled, two professors stood up for us. They told my old classmates at the university that homosexuals are not deviants, which is what the sociology books still called them. So this was an important clarification. At the time, no one knew about transsexuality — neither me, nor them.

When my family found out why I had been expelled, they tried to beat the abnormality out of me. My father would hit me until I agreed to behave as a girl. I was isolated from my friends and I could not get away. This wasn’t unusual. There are many cases in Kyrgyzstan where a trans person who comes out risks being beaten, humiliated, or killed.

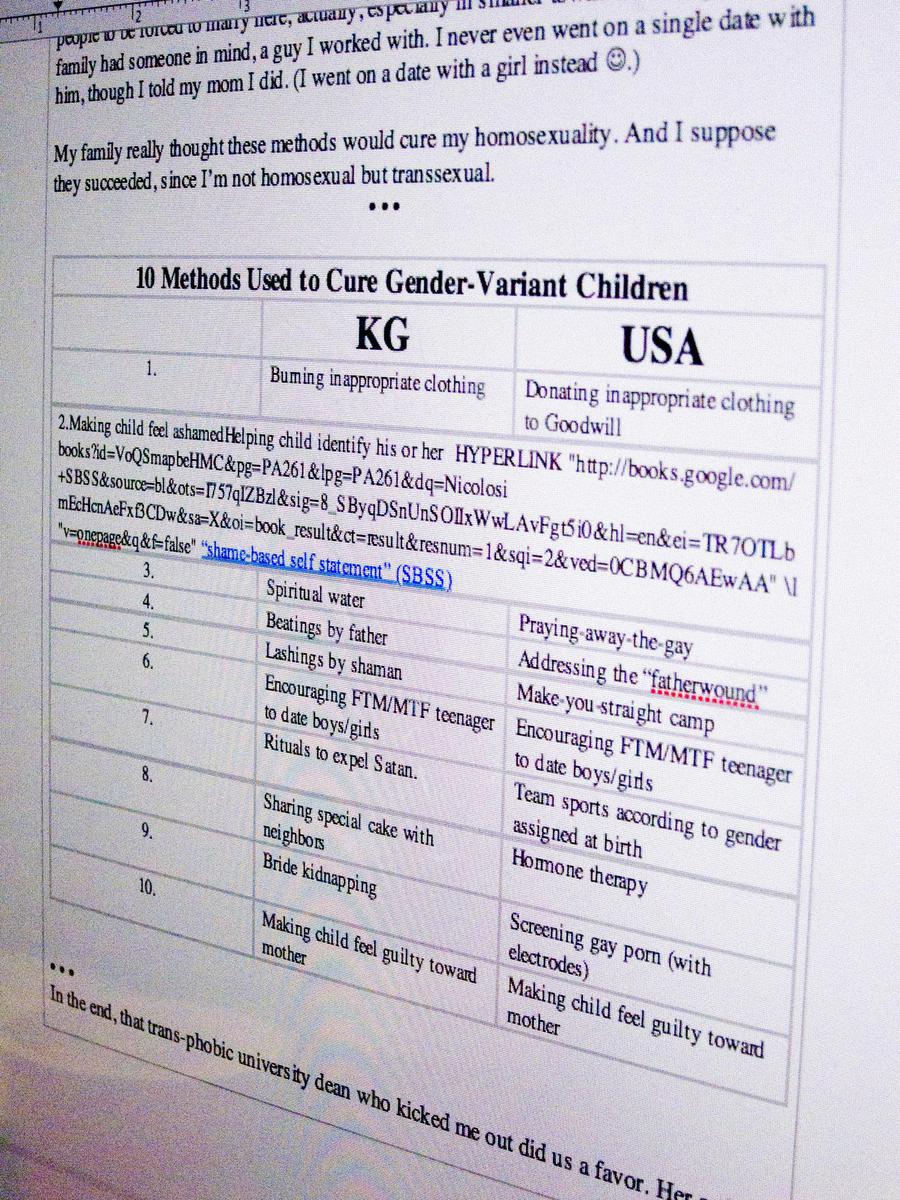

It took me three years to escape my parents’ home. In the meantime, I underwent all sorts of “treatment.” There are so many silly practices; it would take a year to describe them. It was funny sometimes, and sometimes it definitely wasn’t.

My mom took me to see a moldo, which is kind of like a priest. Kyrgyz culture has pagan roots, so I underwent voodoo treatment as well. I had to wash my face and cook with spiritual water, drink special tea, and eat special cakes. Priests and voodoos prayed over this food before I ate it, claiming that it would heal me from homosexuality. The cakes are really just Kyrgyz bread, but you have to pray the whole time while you’re baking them. They’re meant to make sin or illness leave a person, and we’re supposed to share the cakes with neighbors. There are usually seven of them, as this is a magic number in Kyrgyz Islam.

Speaking of seven, I was also taken to shamans; one told me that Satan was inside me, making me who I was, and that it would take seven visits to expel that Satan — visits that included beatings with a lash as well as prayers. Many other trans and gay people underwent these lashings, too.

I knew all of these crazy treatments weren’t going to work, but I went along with a lot of it. I just wanted my parents to exhaust every method they could think of to fight my identity. It wasn’t easy. People would tell me over and over that my behavior was killing my mother, and that my mother would die if I didn’t straighten up. Relatives ignored me. People would threaten to rape my friends or kill me.

Like most Kyrgyz families, my family had strict limits on discussing sexual stuff, but they started setting me up on dates with men. (This is totally unusual in Kyrgyz-Muslim culture; it shows how desperate they were.) They wanted me to get married. My mom thought giving birth would help me get used to life as a woman. It’s pretty common for LGBT people to be forced to marry here, actually, especially in smaller towns and villages. My family had someone in mind, a guy I worked with. I never even went on a single date with him, though I told my mom I did. (I went on a date with a girl instead.)

My family really thought these methods would cure my homosexuality. And I suppose they succeeded, since I’m not homosexual but transsexual.

In the end, that transphobic university dean who kicked me out did us a favor. Her actions led to the birth of the trans-movement in Kyrgyzstan.

When I was in my early twenties, a friend introduced me to two Annas — Anna Kirey and Anna Dovgopal. It was the summer of 2004, and they had just returned from their studies and established a group called Labrys. I visited Labrys a couple times, but stopped going because they were only working with lesbians. I’ve never identified myself as a lesbian, because lesbians are women, and I’ve always felt I was a man. I’m a female-to-male (FTM) trans person. I still didn’t use that term when I met the Annas, though. At the time, I was the only “incorrect person” I knew. At the end of 2005, when I was twenty-four-years-old, I finally left home. For a while I lived out on the street, sleeping in elevators or even outside.

Anna K called one day and asked me to watch a video. She had met this German trans man, Richard Köhler, who asked her if she knew any trans people in Kyrgyzstan. She told him she knew a few, but that trans people did not come to Labrys and that they had nowhere to turn for help. So Richard decided to make a film of him talking to local trans people, which is what Anna had me watch.

Richard, who works with the International Lesbian, Gay, Bisexual, Trans and Intersex Association of the European Region (ILGA-Europe), made this video specifically for trans people in Kyrgyzstan. I will always remember him saying, “No one has the right to humiliate you just because you are the way you are.” That’s the first time I got the message that no one can shame me based on my gender identity, even though I had previously learned ideas about civics and respecting human dignity from the Peace Corps volunteer who taught me English.

After that, Labrys began working with trans people as well as lesbian and bisexual women. I lived in their shelter from November to mid-December 2005, and then I worked for them for a while. We showed Richard’s video to other people — not only trans people, but our partners and friends, and lesbian and bisexual women. Then we started doing workshops for the lesbian and bisexual community on trans-issues, and we started holding transgender support-group meetings.

It took a few years, but my family finally accepted me. They’ve totally come around, actually. When a friend of mine was kicked out of his house, my mother offered to let him stay at their house as long as he needed, until his parents came to realize how much they miss him. Which is what happened with her, of course. My trans friends really appreciate that my parents use the right names and pronouns. They always refer to us as “he.”

These days, I’m a project coordinator at the Youth Human Rights Group, which works with orphan children and young activists, as well as human-rights initiatives in Kyrgyz legislation. My project at YHRG is to prepare an alternative report to the UN Committee on Economic, Social, and Cultural rights. We’re looking at Kyrgyzstan’s situation in regard to the right to the highest attainable standard of health. Of course, we included LGBT issues in connection with access to the health-care system.

Back in the USSR days, psychiatrists treated transgender people with lobotomies, hospitalization, and strong tranquilizers. Older transgender people say the rate of violence against trans people was even higher than it is now. Most of the older trans men I know were raped, and all of them have been beaten many times. Very few have transitioned and most continue to live a double life.

All of my friends are Western-oriented in their understandings of LGBT rights. But I wouldn’t actually call it “Western oriented” as much as “human-rights-oriented.” In any case, we are definitely not Russia-oriented in our work or beliefs. Russia has strong homophobic and transphobic — any phobic, really — ideas about the world. We try to find European models that fit our reality and may be effective in Kyrgyzstan.

I’m still in touch with Labrys as we work toward these changes. Three years ago, Anna K. and I decided we needed to get the Ministry of Health and other state agencies to fill the legal gap regarding trans people’s rights. To highlight the difficulties of life for trans people living in Kyrgyzstan, Labrys made a short photo-comic called T-World. It features a man whose appearance doesn’t match the feminine name and gender on his ID. When the man tries to change his name and gender marker, the passport agency tells him he needs a psychiatric evaluation, but even then he is denied a proper ID. He can’t get a job or travel out of the country, and when he appeals in court, the judge says, “No penis, no passport!” That really happened!

Fortunately, even though our population is Muslim and very transphobic, Kyrgyzstan is a civil state, and on paper our human rights are recognized. Officially, representatives of our agencies are there to ensure these rights. That’s how we began to change the law so that transgender people can change the gender markers on their passports without taking hormones, without surgeries, and without sterilization.

There’s a sense in which, hard as it is to be transgender here, it’s even harder to be gay. When I speak on this issue, I often use the example of Iran, which is a Muslim country where a transgender person can get surgeries because people agree that there are “mistakes of nature,“ but where they do not accept gay people. In Kyrgyzstan, it’s much less acceptable to be lesbian or gay than it is to be a passing trans person.

Unfortunately, even the trans community is homophobic. Older trans people who have not gotten much support often have weird ideas about who is “genuinely trans” or a “genuine man.” This is what I want to work on next year. There are trans people who are hiding their sexual orientation from their psychiatrists because they don’t want to be turned down for treatment.

I have to say, though I never forgot the story my grandmother’s friend told, I never ever thought I would one day have that very surgery. Today there are two clinics here that offer trans-surgeries, and we all know the doctors who do them.

I was among the first six people to undergo the surgery. Our doctors had never worked with trans people before, so the results were not as good as we had hoped. But still, it’s way better than having boobs.