London

Jean-Luc Moulène: Products of Palestine

Thomas Dane Gallery

September 3-21, 2007

Tucked in the quaint Thomas Dane gallery in South Kensington, Jean-Luc Moulène’s ongoing project ‘Products of Palestine’ recently made its way to London. In this exhibition of photographs, taken between April 2002 and November 2004, Moulène presented the entirety of a series of fifty-eight images of products made in Palestine, for Palestine — ranging from olive oil, wafers, and cheese to cigarettes, medicines, and underwear.

Shot against neutral backgrounds under natural light, Moulène’s objects were writ larger than life, magnified. In removing these products from their quotidian situation and by using the codes of advertising, the artist made an unsubtle statement, attempting to ironically spark desire in the eyes of an audience. These objects are far from attainable — marginalized, nonexistent in the international market, just as their manufacturers are themselves marginalized by the political status quo. While their gleaming beauty contrasts bluntly with a reality that we know too well, the incongruity could be a productive one; the audience is bound to feel a sense of discomfort. Why make such an ugly reality a thing of beauty? Moulène’s objects left little space for indifference or passive consumption, as the audience was consistantly invited to raise questions. The photographs operated on different levels, playing with interminable possible meanings. On the other hand, could the photographs be too bluntly ironic? One equivocates and is hard pressed to conclude.

As Moulène himself acknowledged during a conversation with artist Walid Raad on the occasion of the exhibition, there is little hope for a revolutionary Palestine; the only way it can be “at peace” is under the dominion of liberal capitalism. The irony of the photographic presentation was further underscored by the fact that Moulène’s products appeared as still lives — beautiful, yes, but also ordinary, banal. Yet the images were worlds apart from the staid tradition of the still life — by virtue of their being photographs, but also because of their particular subject matter.

Interrupting the seemingly homogenized series of images of foodstuffs were Oxfam products, circulating solely within and tailored specifically for the Occupied Territories. Here one was likely to pause, for these objects stood apart from the rest, a moment of difference located on the periphery of the two large halls of the gallery. And yet, in the end, they also blended in, emblematic of an everyday emergency that has been rendered mundane.

Moulène is not the first European artist to take on the loaded political reality of Palestine, nor will he be the last. But what perhaps made his work stand out was that he also managed to make a statement about the nature of the photograph as an effective tool to document a harsh reality, along with its potentially contradictory capability — to render that very harsh reality flat by turning subjects into objets d’art rather than political objects. Again, the ambiguity was a stimulating one. Moulène was able to reel us into the intimate lives of Palestinians through the products they encounter in their daily lives. Few forms of media, few artists, have been successful in conveying the weight of the Palestinian cause without resorting to some manner of melodrama, nostalgia, or voyeurism.

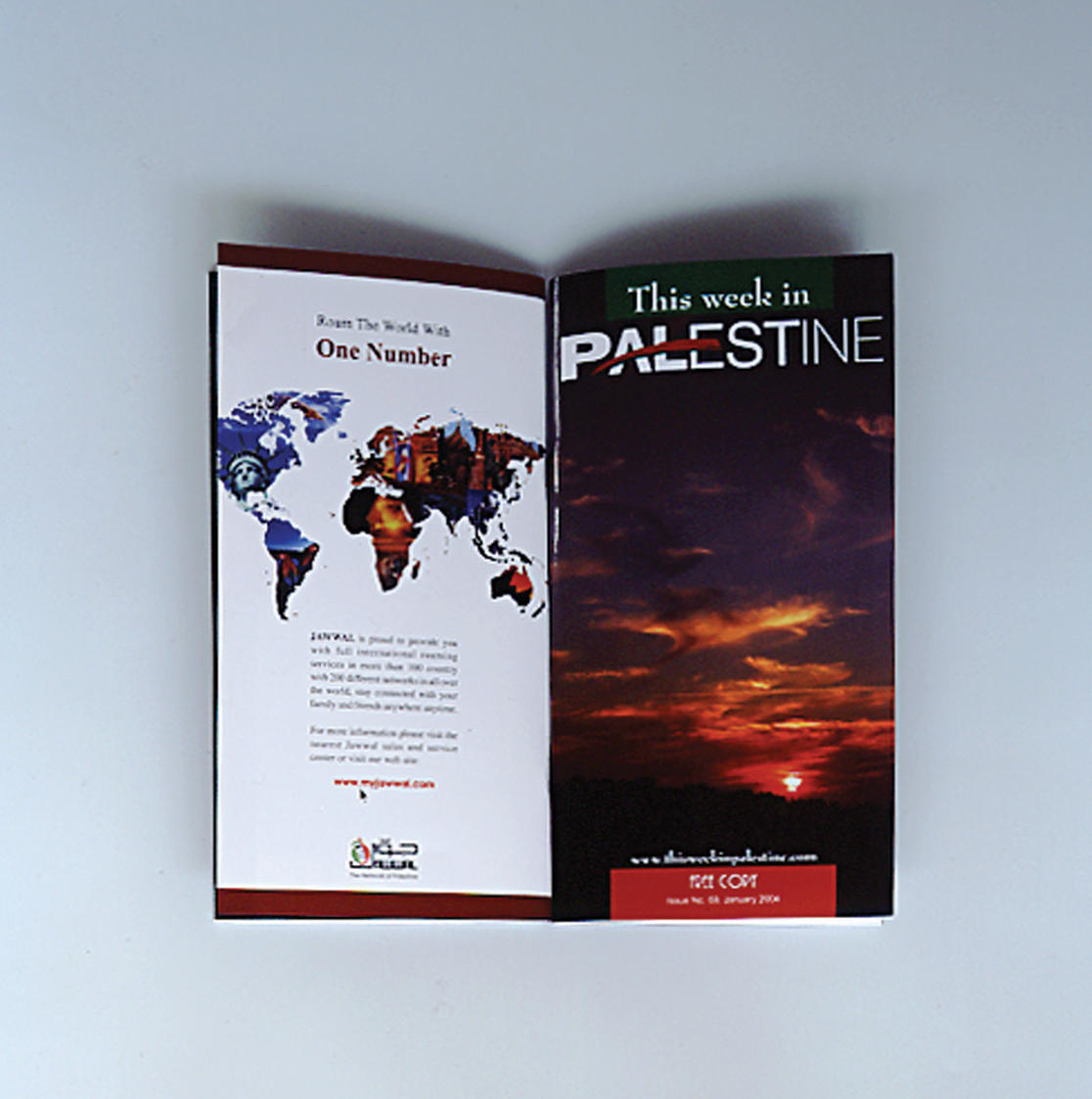

Of all the products Moulène amassed, one in particular epitomized the absurdist nature of the exhibition. That image was — perhaps intentionally — located at the end of a long line. Roam in the world with one number read the Weekly in Palestine brochure. A map of the world beneath the catchy slogan reminded us of the impossibility of that command.

www.thomasdane.com