But aren’t those oak trees?” queried the young Emirati collector, in a cut-glass English accent, as he perused Christie’s recent exhibition of Orientalist paintings in a richly chandeliered hotel in Dubai. An elegant Christie’s specialist assured him that the camping scene was indeed set in Morocco, but that the artist was French — hence, perhaps, the Europeanized flora.

Christie’s opened its first office in the Arab world earlier this year. Based in the Dubai Metals and Commodities Center freezone, its forthcoming calendar of pre-sale exhibitions includes everything from Islamic art to film memorabilia. The arrival of the distinctly old-school auction house in upstart Dubai indicates the growing importance of the UAE market; the city is an easy hop from Saudi Arabia and Kuwait, and a second home for many of Christie’s longterm Lebanese and Iranian clients.

Asked “Why Dubai?,” Isabelle de la Bruyère, a Christie’s Associate Director and Senior Advisor for the Middle East, described the city as “the turntable of the Middle East.” She added “We hope, however, to expand over the years and have a representative office in various countries within the GCC and the broader Middle East. The interest for culture and art is very present within the region, and we simply want to be closer to our clients.” One of her colleagues added, “Well, it’s the obvious place — Jimmy Choo is here after all.”

Of course, Dubai’s reputation as the shopping capital of the East shouldn’t preclude art. “They [local, mainly Emirati collectors] like expensive, beautiful things. They don’t question the value of the [Orientalist] paintings,” one of the sales team said at the pre-sale exhibition in Dubai. “Few of the collectors are art history trained, but they love the exotic nature of the works — they talk about being able to feel the heat of the desert.”

For curators and academics guilt-tripping on postcolonial theories, Orientalist paintings are usually seen as painterly reproductions of colonial patterns of thought, executed in a reductionist manner. Their galloping horses, elegant pashas, draped harems, luscious fruit and agreeable slaves bring out the snob in much of the contemporary art world. But the increasing importance of the Middle East market today leaves these ironies a little out in the cold: To judge the Arab consumption of the Orientalist tradition with this knee-jerk knowingness arguably restricts the analysis to western postcolonial prerogatives.

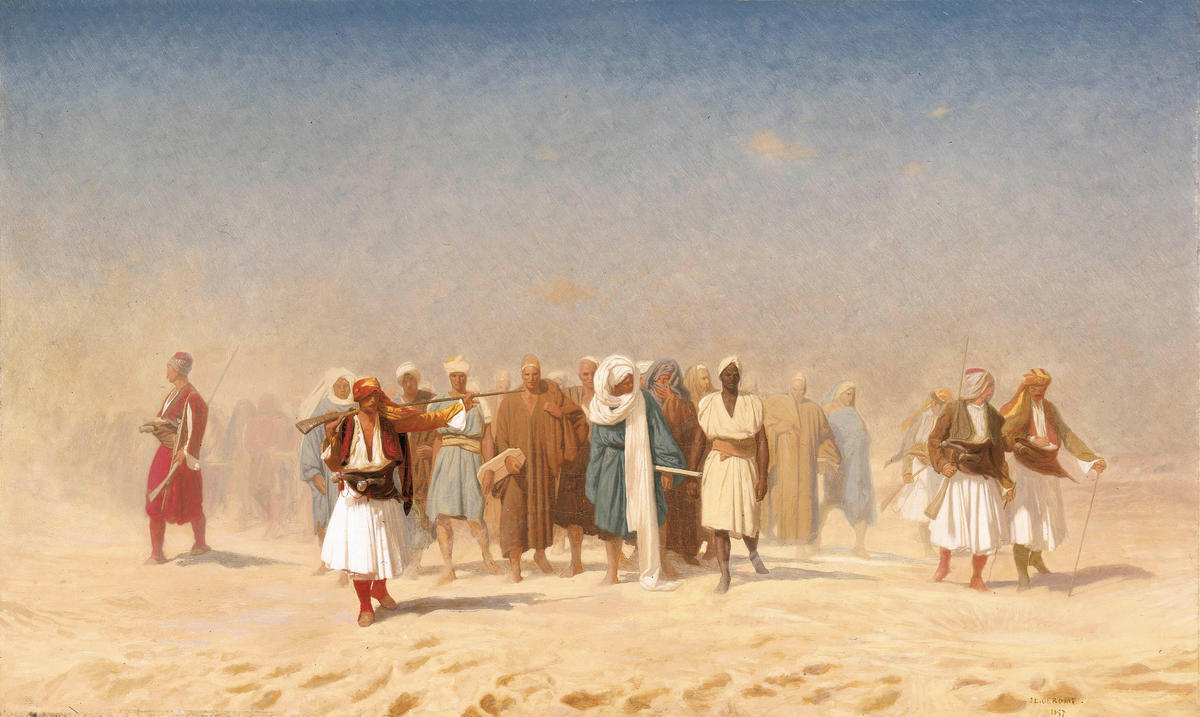

Up until the 1970s, within the rarefied world of art, auctions and conspicuous consumption, these imperial fantasies were seen as something for politically incorrect eccentrics. Sotheby’s 1985 Coral Petroleum sale was the first real indication that the market had changed, and de la Bruyère remembers Christie’s 1993 Forbes magazine sale — over 400 lots, including spectacular works by John Frederick Lewis and Jean-Léon Gérôme — as one of the greatest auctions of Orientalist paintings. At first, American buyers dominated, but over the past ten years, the Middle East, particularly now the Gulf, has come into its own.

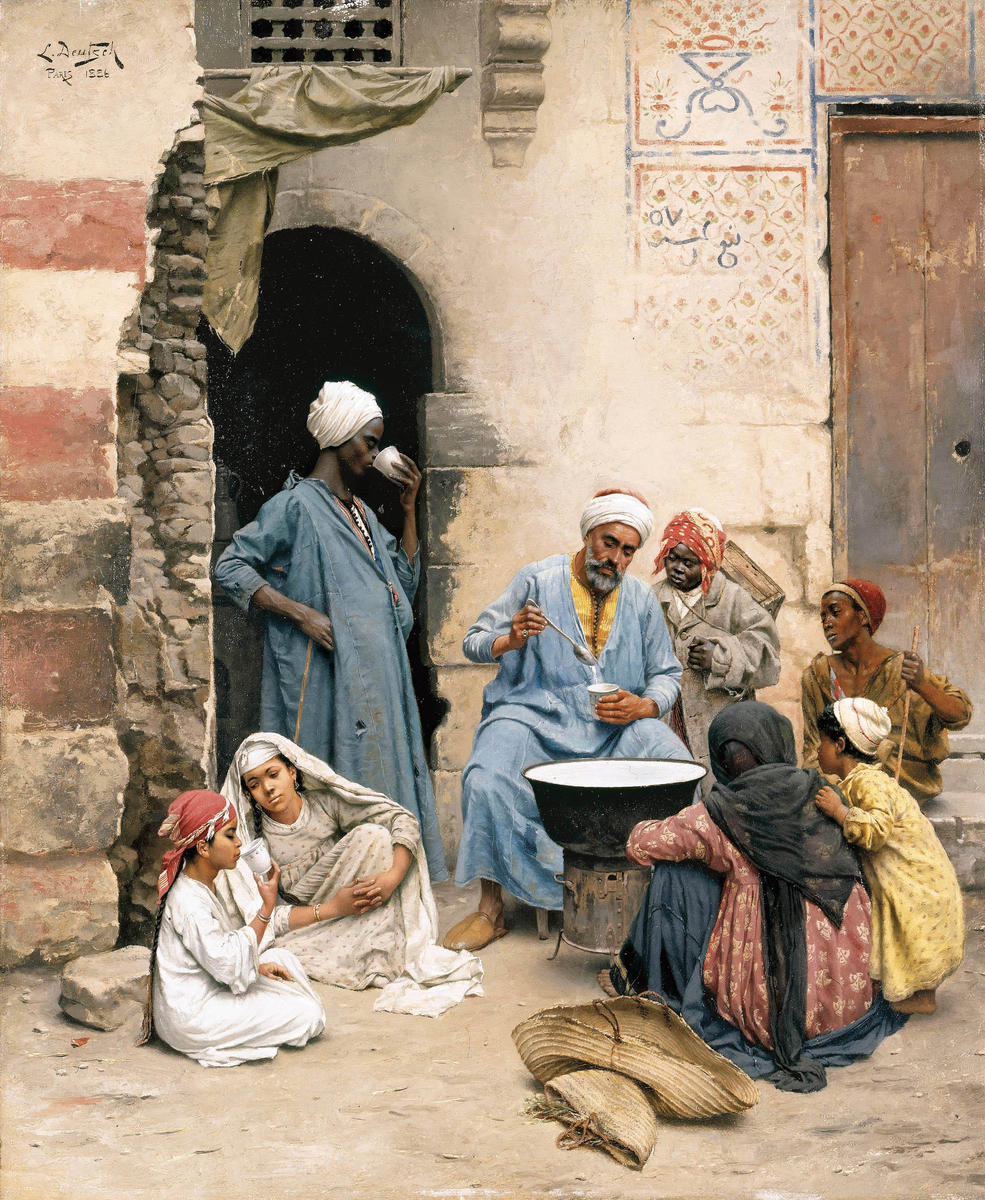

Dina Nasser-Khadivi, a nineteenth century specialist from Christie’s New York, cites the influence of dealers in London, plus the rising numbers of Khalijis studying and traveling abroad. She adds, “They appreciate the aesthetics, particularly the detail — artists like Lewis, Gérôme and Ludwig Deutsch are very popular. Of course, it’s part of their heritage.” (Naturally, Julius Victor Berger’s harem fantasy, Entertaining the Pasha, part of the June 15 sale, was left out of the Gulf tour.)

The heritage debate beings us back to the latent irrelevance of authenticity — after all, most of these paintings depict scenes in Egypt and Morocco, the sites of the European “grand tour,” rather than the Gulf. And if, for Gulf collectors, these paintings offer an artistic reality, where does that leave the naysayers of the postcolonial contemporary art world? Perhaps Gulf collectors are reacting to these works in the most contemporary, post-postcolonial way — in terms of aesthetic appeal and nostalgia for a place and time that never was, but that reverberates pleasantly in transnational memorial.

Gulf collectors’ commitment to the genre can’t be underestimated. At the actual sale — a private collection of thirty Ottoman and Orientalist paintings in London on June 15 — Christie’s sales totaled 6.9 million dollars. Lewis’s The Midday Meal, Cairo, the top lot, sold for over $4.4 million and shattered the artist’s previous record. Speaking to Bidoun after the sale, de la Bruyère noted the “enormous bidding activity” from the Middle East, particularly the Gulf. Five of the top ten lots were sold to private Middle Eastern buyers. Lydia Limerick, who heads up the Dubai office, noted, “We’re the first auction house to have a permanent presence in the region, and delighted that the results confirm the growing importance of the market.”

Although attendance and results have been poor at recent Islamic art sales, it’s the high-profile doyens of this market — Londonbased Nasser David Khalili, Sheikh Nasser Al Sabah of Kuwait, and until late last year, Qatar’s now-disgraced Sheikh Saud Al Thani — who dominate the auction room headlines. It’s mainly in this context that commentators track the gradual movement of works from western art collections “back” to the Middle East.

When it comes to the Orientalist art market, Christie’s says that collectors in the Gulf tend to buy the works for display in their homes, rather than as an investment. (If this trend continues, it could presumably result in a hike in prices, as it becomes increasingly difficult for auction houses to source important collections for sale.) The big stumbling block in the region is the lack of major public museums; Sheikh Dr. Sultan bin Mohammed Al Qasimi, ruler of Sharjah, remains one of the few collectors whose collection of Orientalist paintings is on public display (in a new museum within the city’s arts and heritage complex).

Orientalist artists’ experiences and agendas were diverse: For every Giulio Rosati (1858–1917), who never left Italy and conjured up his harems and desert raids in the sanctuary of his studio, there was the likes of Lewis, who embraced the Middle Eastern experience, living out his fantasy life as an Ottoman nobleman in Cairo’s Ezbekieh district.

Not that the essentialisms of the nineteenth century European project have been totally laid to rest. Conversations between uninformed western gastarbeiter in the bars of the Gulf, as well as between many art world experts, peddle the worn line that the Gulf is an irony-free, uneducated market, where collectors embrace stereotypical visions of their heritage — from Orientalist paintings to contemporary watercolors.

It’s easy to chuckle knowingly at the fact that, should you not be able to afford Lewis’s A Midday Meal, you could pop along to hotel Mina A’Salam in Dubai’s Madinat Jumeirah, a vast, new mock-Arabian palace, and see a reproduction hanging in the Bahri Bar, all dark timber and exotic cushions, with an ersatz traditional water taxi, floating by the man-made creek below.

For the cities of the Gulf, playing catch-up with older capitals, the public relations game is key. Both internally and externally, these fast-growing cities compete to project polished images of themselves as successful and sumptuous. The idealized postcards of Lewis, Gérôme et al appear to perfectly complement the Middle East’s new urban fantasy.

The (recent) past, on the surface at least, has become highly stylized, from architecture that appears to borrow selected local historical elements — such as Madinat Jumeirah’s adobe-colored windtowers — to the lingua franca of Gulf-based advertising agencies — the noble, bearded old Bedouin, the rolling sand dunes. The past is a mysterious, exoticized pastiche — but of what? After all, the trading nations of the Middle East have been engaged in East-West banter for hundreds of years, dealing back and forth in the icons of exotica, producing a mishmash of references that muddies the notion of “authenticity.”