O Egypt is there a wise man in your midst — for my mind today is made of steel.”

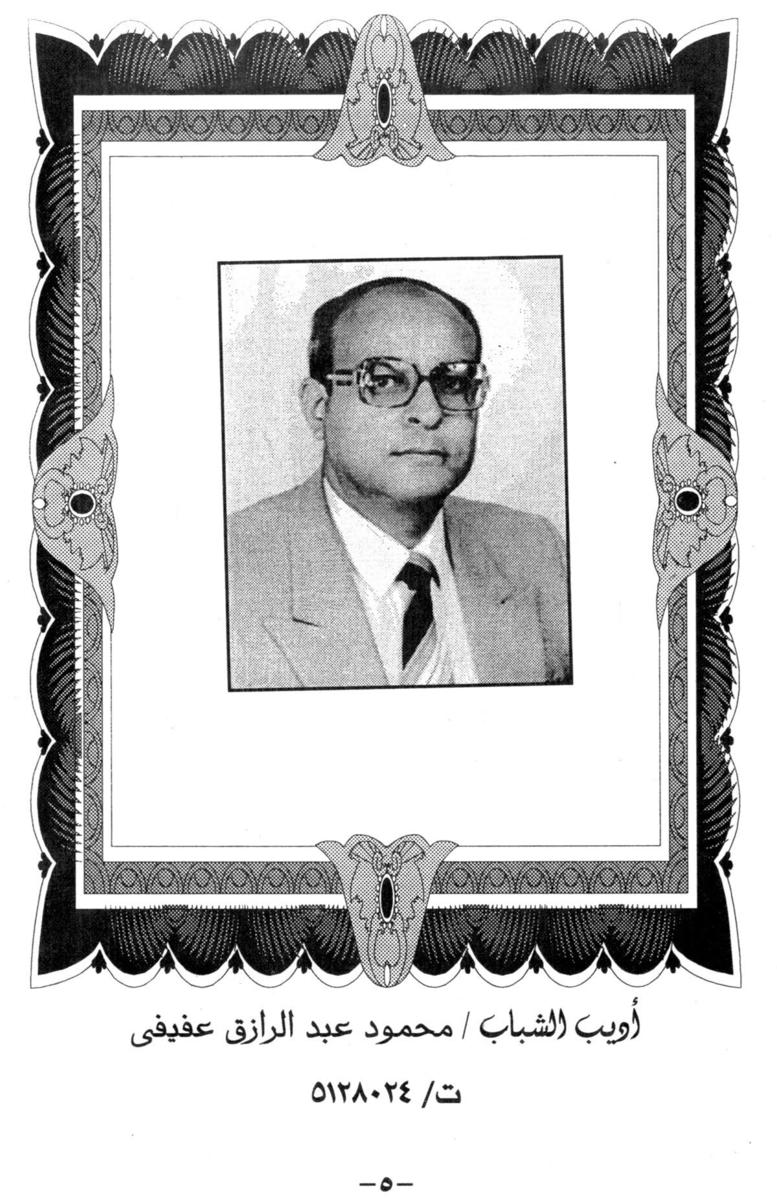

—Mahmoud Abd El Raziq Affifi (Adeeb el Shabbab), street graffiti

POSSESSION AND DISPOSSESSION

According to popular legend, Mahmoud Abd El Raziq Affifi, the self-styled Adeeb el Shabbab (writer of youth) exploded into the consciousness of this city sometime in the 1970s, when he paid street kids to lift banners advertising his books at football matches that were broadcast live on national television. Over the years he honed his skill of self-promotion and by the late ’80s and throughout the ’90s Affifi had blitzed the walls of the megalopolis with bold provocative statements: quotations from his many books, direct challenges to images of literary icons, and even petitions to the president. This was how I first encountered him and his language of taunts, self-deprecation and preposterous claims — the productions of a logic so severely skewered by desire, fear, insecurity, misogyny, envy, megalomania, and an obsessive blind lust for recognition.

And how I wish to ascend to the divine presence to meditate upon the earth and the heavens and bygone eras that I did not have the chance to live in, and how I wished that I not meet my maker before the whole world is in the clasp of my hands.

—Affifi, street graffiti

SUPERIORITY, INFERIORITY AND FEAR

Abd El Raziq Affifi functions within a dark place. Moments from his biography: Letters to belly dancers, writers, journalists, and academics; notes on different public figures; theological theses; philosophical and political analyses; sexual fantasies; fictions portrayed as real events; memories included in fictions; and late night phone conversations with his readers are all mixed together in one huge tapestry of pathology. His is a meta-discourse that transcends genre. With such titles as “This is my Qu’ran,” “Divinity and Sex,” “Stories of the Whores,” “Words on Rolling Paper,” “Who will Swim against the Current with Me?,” and my personal favorite, (the almost unbelievable) “Folly in the Vagina” he has managed to produce objects rather than descriptions, and to unwittingly map out the culture’s collective psyche. We go from electrocuting an old blind woman as a kid (connecting live wires to her brass bed), to a memory of his mother milking a cat in the cupboard to feed him, to an older Affifi who leaves buckets of his cum for the neighborhood women to dip their fingers in as a blessing. This intensely misogynist street philosopher has offended everyone, consistently contradicted himself, and wittily deconstructed the intellectual establishment, all while proclaiming himself a religious conservative, secular rationalist, authoritarian dictator and democratic liberal.

Claims abound: An incessant, often-contradictory catalogue of sexual conquest is suddenly offset by an obscene, blatantly neurotic assumption of a gay voice. His fear and envy of police officers, judges, famous journalists, governors and municipal bureaucrats leaves us with a secret history of signs, twitches and gestures, the marks of control and possession. On one level he wants to be everything he is not, while on another he considers himself to be above it all — much like a thanawiyya amma (Egyptian High School General Certificate) student who hopelessly fails his exams and claims that all he wanted to ever be anyway was an actor. Affifi — the text — is himself an argument for failure, one endemic to the current social structure. Therein lies his value.

M. President, how could this happen while we live in the era of greatest freedom — I will be forced to sell my kidney because of GMC and Olympic Electric, who refused to pay for the advertisements that I placed in my books.

—Affifi, street graffiti

PSYCHOPATHOLOGY AS A LAYER OF THE CITY

Maybe Adeeb el Shabbab’s significance lies in his extreme pretentiousness. This is a man who dared challenge all the literary, religious and political figures of modern Egyptian intellectual history, thick on the streets of the city, no less. The gesture radically refused, imposed and promoted hierarchies, in an intellectual climate where figures are sanctified and critical texts are disguised hagiographies. But it is important here to draw a distinction between a conscious artistic strategy and the obsessive impulses of a person who is essentially on the margins of society. Affifi’s texts are marked by a hysterical love — and hatred — of the mainstream. Even if there has been a seeming shift lately in the power structure, from a specific type of veiled provincialism and state-sponsored bureaucratic fetish to the suave Gucci clad clones of the early twenty-first century, ruptures are never as real as they seem, changes are easily cosmetic, and Abd El Raziq Affifi’s rants remain relevant indices of the pressures of living in hierarchical societies. But it is necessary to seriously engage with productions of the margins, with the uncontrolled and the defective, in order to trace dysfunction itself and discover forms that are wedded to their context. These forms might well be situated in the alleyways of Al Imam el Shafei, rather than in the hip galleries of contemporary art or the self-important circles of literary debates. And maybe it was necessary to go to hell and back to approach the complexity of a society that continues to speak in two tongues.

O people of Egypt do you not want to witness the birth of a new dawn? Yes — for these are my words eternal monuments on the banks of the Nile so that our descendants would know how ancient this land is.

—Affifi, street graffiti

PLEASURE SQUEEZED OUT OF WORDS

In his chapter “On the phone with the readers,” Affifi transcribes his often lewd late night conversations. Speaking to lonely men in the middle of the night is a chance for Affifi to air his fantasies — a mixture of the cheap hedonism of ‘80s Egyptian movies and the bitterness of someone who has been shafted all his life. Veiled beneath these fantasies are not only darkness and loss but also form, a way of transforming the action of language into a modern ritual, a method of supplication. Whether it is being married to four Egyptian sex symbols at the same time (taking their onscreen flirtations one step further, humiliating the image itself) or prostituting his wife (turning social norms upside down, insulting manhood itself), Affifi is both the victim and king of these images — teasing out pleasure in the very telling, the drive to expose and the vertigo of our obsessions. In that sense he differs radically from the pornographer who attempts to entice the reader. For Affifi, pleasure is essentially the pleasure of the self, a masturbatory act. The hysterical overflow of words (on every page — front cover, back cover, and inside leaves) is a sign of his pleasure taking. This is the pleasure of someone who knows that his texts are his only chance at redeeming the self and by extension the world (he collapses the two). It is thus one easy step to move from the literally erotic to the religious. Through this transcendent impulse, his ego can mount the mantle of world domination — and in classic “I will rule the world” madscientist style Affifi informs us that if George H. W. Bush visited him in his house in the Imam El Shafei cemeteries, he would give him a piece of his mind.

Yes that is the state of the majority of the Egyptians and if it wasn’t for what’s left of civilization, tradition and history we would have been a group of barbarians; for these are a people who should be whacked on their genitals so that they may return to their rational faculties.

—Affifi, street graffiti

PAIN TRANSFORMED (OR WHO’S BOURGEOIS OUT HERE?)

If the bourgeoisie are historically marked by their constant aspiration to seem something more than what they are — to move from the position of watching the great orgy of consumption to being empowered as direct participants in those pleasures — then outsiders like Affifi (who is firmly placed in an educated lower middle class) suffer both from being shunned by those higher and the inability to truly practice the unfettered crimes of those who operate on a lower level. Twisted by guilt, Affifi is the unmasked bourgeoisie in its most raw manifestation. Or as one Cairene succinctly sums up, “Here you either ride or are ridden.” It might be that for Affifi his practice promises a certain redemption, a coming to terms with that context of specific hegemonic discourses — religion, customs, traditions, socially appropriate behavior and, quite significant for him, the law. His experience of pain, whether inflicted on others or experienced by himself, is one which comes quite close to a certain form of pleasure. It is as if through pain, Affifi comes to terms with an order that he will never be able to rule, an order that has not only assigned him a position but shaped his very tools of perception. His whimpers, at once defective and aspiring to perfection, become destabilizing impulses within that order. But more important, they promise us the hidden pleasure of consuming our own collapse, the entertainment of watching our moral structure being messed with. Affifi’s readers — the socialized citizens, family members, students, workers, criminals, intellectuals, political activists, housewives, or policemen — who might one day accidentally pick up a copy of his books from any street vendor might be secretly fascinated by a text whose voice seems to come from a secret location inside them, rather than speak about who they are.