Steve LaFreniere: I recently read an essay that describes your work as “tight-lipped in the Warholian manner.” I thought that was pretty funny.

Richard Prince: I’m not sure what it means. Close to the vest? All-knowing? Effortless? I remember seeing Warhol interviewed; he let someone else answer the questions for him. He just sat there smiling, like he was throwing his voice. “Tight-lipped?” I’m thinking it might mean "ventriloquist.”

—from Artforum, March 2003, XLI No.7, page 70

A friend and colleague, Ellen Langan, once pointed out the dubiousness of our referring to the goings-on of the art market as “the art world.” Ms Langan observed that, indeed, there is no doctor world, no law world, and finance is just called finance. Why don’t they exist on their own planets, too? Maybe it’s because the larger meaning behind these influential trades is easier to understand than is that of the art world, so the public cares more about interacting with and monitoring them. Even if one wanted to monitor the art world, its system makes the task unworkable. Contracts are seldom exchanged therein; instead the art world’s various arms (producers of art, marketers of art, distributors of art, consumers of art) function through the exchange of words. These “arms” don’t usually like to pay each other — either monetarily or in terms of verifiable information — so the idea is to keep everything in a nebulous, untraceable zone where the buck stops nowhere.

Concerning dealers: these arbiters of the next big thing are, of course, not elected, and are barely regulated by any federal organization (though talk of Larry Gagosian’s alleged uptown FBI raid in the aftermath of a silently-settled 2003 tax scandal still remains fodder for an art world-insider rumormonger). Even so, whoever they are and wherever they come from, dealers’ industry sway at this point trumps even that of the elite collector who seeks their wares; it is up to dealers to choose their sales in a market brimming with eager, wealthy art buyers mostly vying for the same hyped things.

At some major art fairs, particularly keen collectors occasionally feel it necessary to enlist the illicit help of a dealer (who might expect substantial purchases in return) in order to gain early entry to an event with forged press passes. From beneath the sheltering brims of baseball caps, these collectors have first dibs in the mad dash to invest in the art market. Preview-day at an art fair is not unlike the floor of any stock exchange; the predatory environment prohibits the collector from contemplating a work for any reasonable period before offering to purchase. Outside the crowded walls of a fair, collectors must often lay hasty claim to an artwork based on nothing more than a jpeg.

At best, jpegs tell hazy stories about the artworks they depict; but often these placeholders alone not only sell artworks but also position them in exhibitions and afford them extensive press coverage. Every email disseminating a jpeg of an artwork builds that particular work’s import and force in the art world. There is quite a poetic logic, to the rise of the jpeg in art world business; in Andy Warhol’s wake, the omnipresent appropriated image speaks a language from which the jpeg derives its vernacular. Appropriations are rumors about their sources, their meanings predicated on, yet distanced from, everything once held, still held, and potentially held by the original source material.

Richard Prince, who succeeded Warhol as the “crown prince” of the appropriated image, builds much of his project around the peculiar dominance of appropriation over originality. In 1984 the now-legendary Prince opened the doors to his tiny gallery, called Spiritual America. Of three exhibitions staged, one in particular continues to enthrall the art world. In it the gallery space was left dark, save for one spotlight shining on the gilt-framed image, also called Spiritual America, of a ten-year-old Brooke Shields. She stands naked in a steaming bathtub, her body polished with oil, her arms open and resting on a ledge, glinting metal figurines positioned around Shields in the foreground and background. The original image was taken not by Prince but by the commercial photographer Gary Gross, who famously executed the shoot in 1975 with the blessing of Shields’s mother. In what has become his signature mode, Prince “rephotographed” the commercial image and then inserted it into his version of an art world environment.

Despite the obviously titillating nature of Prince’s exhibition, at the time, the venture went almost completely unvisited and without mention. The appropriated Shields image, the Spiritual America gallery project, and Prince as auteur accrue their value through an exponentially growing mythology. Even in the last few years, Shields’s role as modern poster-mom magnifies anew the prurience and oddity of the Prince image and the manner in which it was displayed.

And of course, Prince’s contemporary fiscal achievements are the stuff of legend: in 2005 he set the then all-time auction record for any photograph, at $1,248,000. This record was set by a rephotograph of an existing commercial image (in an edition of two with one artist’s proof) and was only just broken last February by a unique Edward Steichen piece from 1904. Meanwhile, artist-run spaces become more de rigueur with every passing year, and the number of artists working with appropriated imagery grows steadily with no signs of slowing.

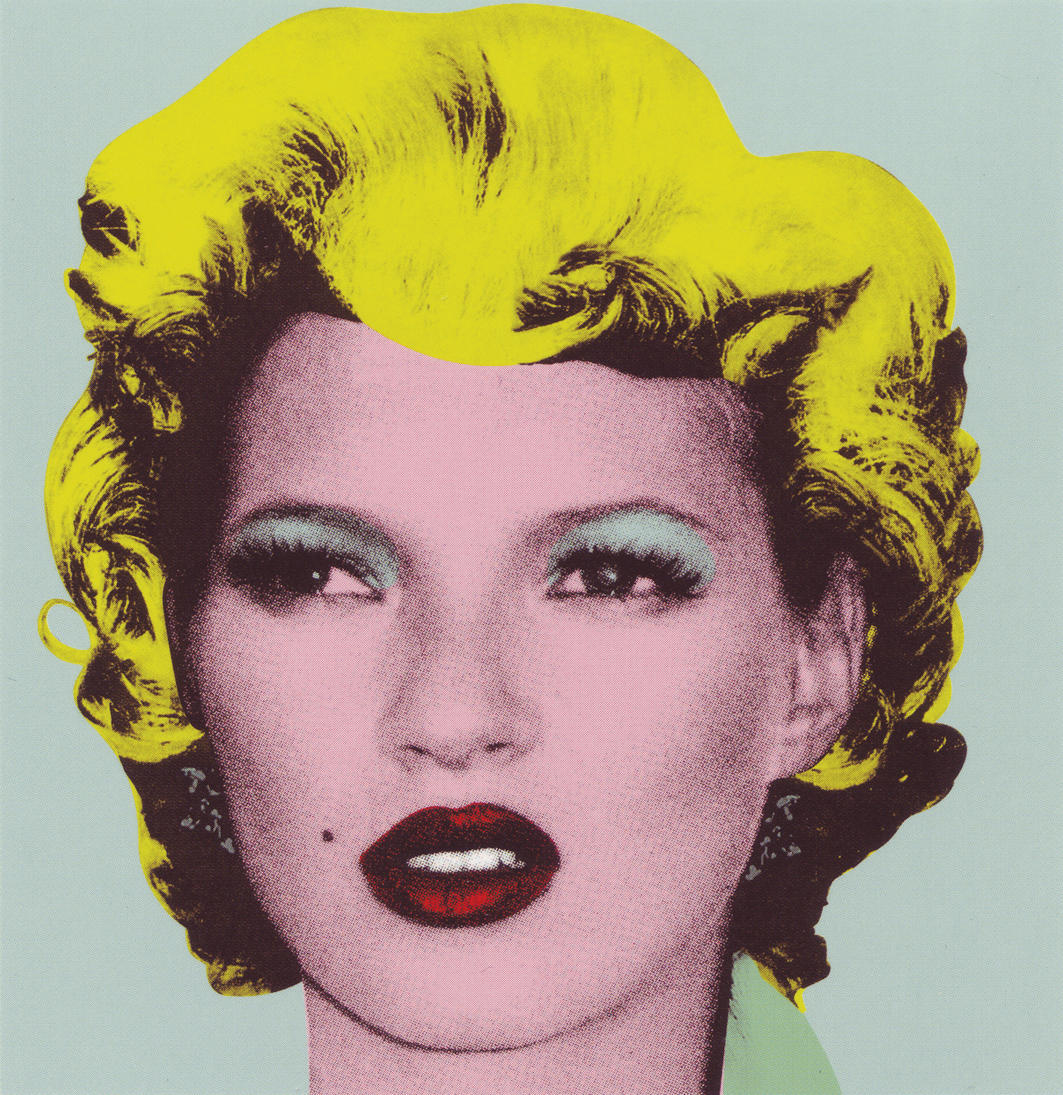

Consider the British artist known as Banksy, who is currently staging a coup on our PR culture to resounding success. Aided by his glib website, www.banksy.co.uk, and regular press coverage of his antics in print media such as The New York Times and The Guardian (these articles are posted in the “Cuttings” section of the artist’s site), Banksy’s self-consciously blasé exploits beget easy celebrity. He sneaks into the world’s most revered museums and hangs spray paintings of his own. He describes beer-fueled evenings illegally stenciling the insides of local tunnels with friends to create a “gallery show.” At Sotheby’s October Contemporary auction in London, Banksy’s 30” x 30”acrylic and spray-paint stencil on canvas, depicting the Mona Lisa (very much a nod to Warhol), earned its position as the cover-image on the auction catalogue, as it set the artist’s hammer record at £57,600. Perhaps more emblematically, his set of six silkscreen prints of Kate Moss’s controversial face, this time explicitly in the style of Andy Warhol’s Marilyn pieces, fetched £50,400. So who is Banksy, to suddenly command this level of capital interest? It’s alleged that he was born in 1975. Other than that, not much is known about the artist, who is somehow attributed with reinventing and popularizing graffiti art, even though it has long remained ubiquitous both inside and outside the gallery environment.

Unlike Warhol, Bansky does not exist in our midst. Curiosity leads one back to Banksy’s website for clues with which to uncloak the masked marauder. What one finds, by and large, are the contradictory musings of a spurned kid. The “Help” section of the site includes a list titled A Guide to Cutting Stencils, offering some of Banksy’s more philosophical musings: “The time of getting fame for your name on its own is over. Artwork that is only about wanting to be famous will never make you famous. Any fame is a byproduct of making something that means something. You don’t go to a restaurant and order a meal because you want to have a shit.” Making something that means something. O days of precious irony, where did you go?

In an age when Warhol’s fifteen minutes of fame can be stretched to years, the key seems to be to shroud one’s popularity in order to preserve it. Express opinions through your publicist, put a jacket over your face, and wait for the glory. When Brad and Angelina are snatching up Banksy’s artworks to the purported tune of $400,000 (to say nothing of gossip column coverage), it follows that Banksy is as much a fantasized organ as the Jolie-Pitts. Both public figures magically transform desire into value – then multiply their celebrity stock values by desiring one another. (Hollywood’s version of star power must at least answer to a measure of sexual arousal and also bow to a wider-reaching, sometimes proletariat audience; the art world’s valuations are mainly exclusive and arbitrary.)

In The Philosophy of Andy Warhol (From A to B and Back Again) (1975), Warhol writes, “I think ‘aura’ is something only somebody else can see, and they only see as much of it as they want to…You can only see the aura on someone you don’t know very well or don’t know at all.” Whispers about people and about artworks are not only much hotter than facts, they are far more convenient, because a swirl of energy never has to substantiate itself to be successful. In the art world, hearing is usually believing — sometimes even from the mouth of a dummy.