Beirut

How Nancy Wished That Everything Was an April Fool’s Joke

Masrah al-Madina

August 30-August 31, 2007

No one named Nancy plays a role in How Nancy Wished That Everything Was an April Fool’s Joke. April Fool’s Day isn’t mentioned either, though some may recall that Lebanon’s civil war started in April 1975.

Slapdash as its title may seem, the latest theater piece by Lebanese artist Rabih Mroué and his collaborator Fadi Toufiq was exacting, at times amusing, and ultimately profound. A veritable Fire Sermon on how communitarian politics seduces and wastes both ideals and ignorance Nancy continued the genre-splicing experiments of Mroué’s earlier work.

Like many of the plays Mroué has made with his partner, Lina Saneh, Nancy eschewed the antiquated theater conventions of plot, action, and characterization. It favored monologue, the simplest narrative form, as mediated by technology — by, specifically, the video screens integral to Samar Maakaron’s stage design. Monologue and monitor acted as mutually reinforcing metaphors for Mroué’s concern with mediation and identity.

Conceptual as Nancy was, though, old-fashioned storytelling still drove the work. Its four characters — played by Ziad Antar, Hatem Imam, Saneh, and Mroué himself — were all Lebanese citizens and civil war militants. They took turns recounting their experiences from the beginning of the civil war in 1975 to January 2007, when street-level sectarian conflict briefly returned to Beirut.

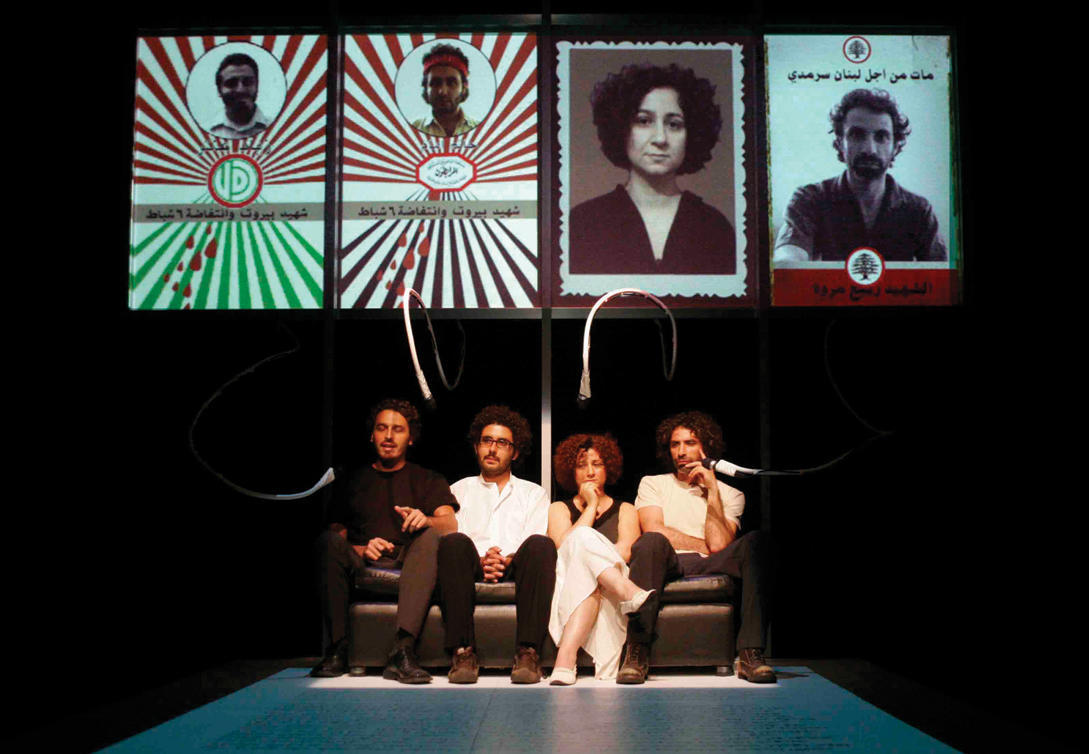

There wasn’t much action. The characters sat snugly beside one another on a couch, speaking only to the audience. At no point did they address one another. Their overlapping accounts sometimes differed, and Saneh’s character at times interjected different dates — whether to correct one anecdote’s chronology or to underline historical motifs, such as Israeli invasions (1978 and 1982) and sectarian massacres (1860 and 1983).

Suspended above the stage were four large rectangular screens, featuring larger-than-life portraits that changed to reflect different phases in each character’s political career. Designed by Maakaron, these were modeled on a collection of civil war-era political posters compiled by graphic artist Zeina Maasri.

These political poster-portraits were significant because all four characters changed their party affiliations several times during the course of the play. As the action progressed, each was killed, only to be reanimated and killed again.

Mroué’s oeuvre is complex, referencing a range of subjects including Lebanese history and politics and European and American artistic practice. His ideas are best realized in his plays, but those are of a piece with his audiovisual work, in which portraiture sometimes makes a strange alliance with death. Witness the 2003 video Bir-Rouh bid-Damm, wherein grainy images obliterated the individuality of mourners at a Muslim funeral. In the 2006 exhibition ‘Hadith: Conversation,’ the artist playfully recreated several masterworks of conceptual art. In each, Mroué either juxtaposed acts of individual eccentricity with images of the mass political rallies that took place in downtown Beirut in the spring and summer of 2005 (Self Portrait as Fountain and Leap into the Void) or else addressed issues of “essential” sexual (and, here, religious) identity (Conversion). His self-referential works chose (inherently individualistic) artistic practice over the sort of group-think embodied in communitarian politics.

Far from being mere ornament, the audiovisual component of Nancy played off the characters’ performances to create a hybrid of theater and installation art. Antar’s character, for instance, related that after he was killed in 1976, “the Communist Party asked me to apply for membership, so they could print a black and white poster of me.” His image appeared with the slogan, “The Hero of Sannine, comrade Hatem Imam.” When he was killed again later on in the war, his body was claimed by a Palestinian organization.

Issues of representation and celebrity-consciousness were a leitmotif among the male characters. Mroué’s character described how, after being killed the first time, he became close to party chief Dany Chamoun and met stars like Charles Aznavour and Julio Eglesias, who wanted to be photographed with him. He was famous. After being killed again, in a Hizbullah attack on South Lebanese Army positions, Mroué remarked, “Around five years later I had the chance to watch this operation on a video Hizbullah had made….I bought it at the book fair in Beirut.”

The paradox at the core of the political posters was compounded as the dead went on to die again and again. Each character’s individuality was subsumed within a religious group identity, and the martyrs’ posters become celebrity photos for the politicized sect into which they were absorbed.

As the four tales converged upon the same point in time, the communal confrontations of January 26, 2007, the characters gravitated to the same landmark — the Murr Tower, an infamous civil war–era sniper’s nest. The four screens portrayed a single image, a panoramic view of Beirut, the tower at its center. The human characters were gone.