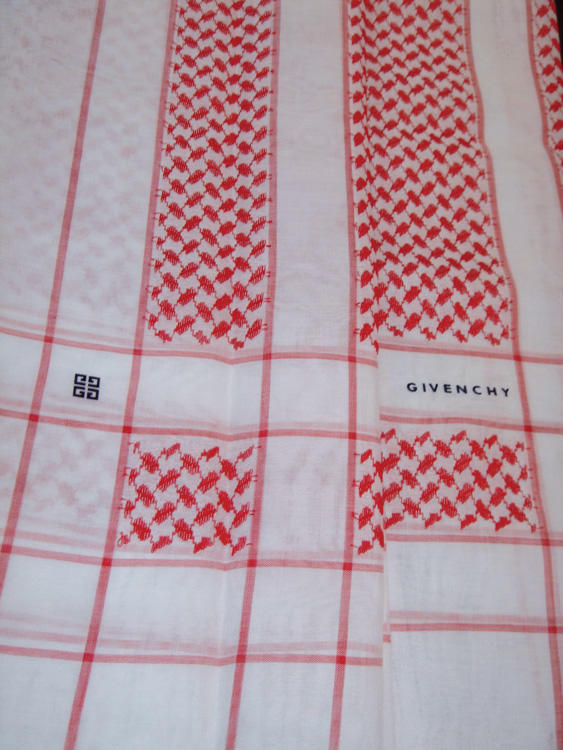

Givenchy / 68.50 USD / Sumptuous, heavy, silky, profound. Slips easily, needs a brooch or pin to stabilize (Bidoun recommends Givenchy’s matching brooch with the insignia of the Spanish Order of the Golden Fleece).

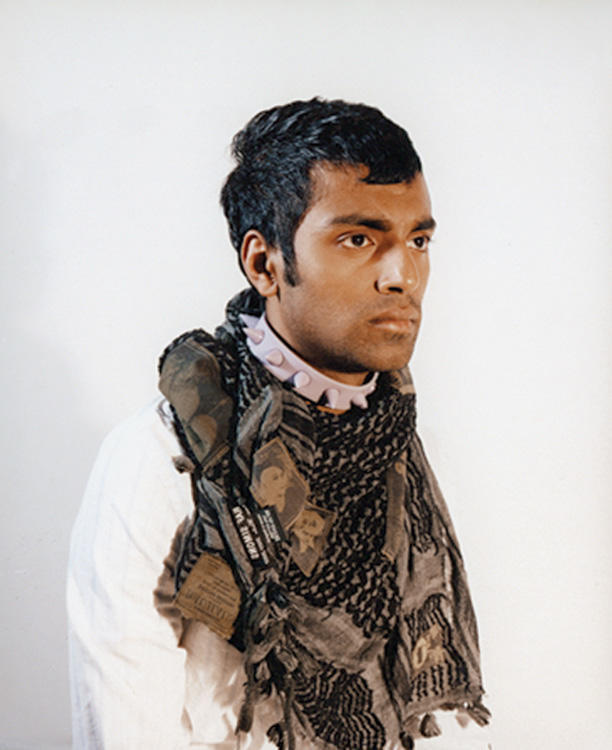

L’éudiant de gauche / 12 USD / Light, coarse to the touch, goes well with light blue 501s.

Ralph Lauren / 125 USD / Sporty, sassy, feisty. Terrific with jodhpurs and/or moccasins.

Le Hizbollah du quartier / 2 USD / Made in Saudi Arabia, worn by Islamic militia in Iran. Boyish and outrageous. Tears easily.

Pop journalist Tom Wolfe coined the term “radical chic” in his celebrated description of a 1966 Black Panther fundraising party in Leonard Bernstein’s apartment. Radical Chic was black power rhetoric through a mouthful of Roquefort cheese and crushed nuts — the frisson of urban guerilla warfare without messing up your manicure. Ever since that legendary Manhattan soirée, the genealogy of politicized commodities has become ever more opulent and absorbing, and indeed commonplace. From the afro to the Mohican to the now proverbial Che Guevara T-shirt, radicalesque posturing has become part and parcel of the day to day fashion. In today’s context of institutionalized détournement and unapologetic pastiche, it takes a lot more than a dinner party to be suspected of sincere affiliations of any kind.

Which brings us to the kaffiyeh. Though left-leaning students across western Europe have been wearing the traditional, black-and-white patterned scarf since the mid 1980s, the accessory has now caught the attention of Givenchy, Ralph Lauren, and the like. Some will scream appropriation — warning us not to empty the icon of its political brunt, of its pro-Palestinian credence — while others will applaud its entry into the influential spheres of the bourgeoisie and the sneaking acknowledgement of the Palestinian cause along with it. At the very least, one might say, its desacralization might raise an interesting questions or two.

Does, for example, the recontextualization of the kaffiyeh create a new object entirely, or does it reveal an aspect of the scarf that was inherent in its appearance anywhere outside Palestine all along? In other words, was donning the kaffiyeh in Cairo, Tehran, or a Berlin University — as opposed to say, Park Avenue, Dubai, or Milan — so removed from radical chic in the first place?

The hottest spots in hell are of course reserved for those who maintain neutrality in times of moral crisis, but Bidoun adamantly insists on its readers’ right to choose for themselves, and will content itself with the critical presentation of the goods now available.

Rumors of a latest kaffiyeh variation in Burberry colors — the “Shropshire Intifada” — were not confirmed at press time.