Istanbul

Haris Epaminonda: Vol. IV

Rodeo Gallery

October 10–December 5, 2009

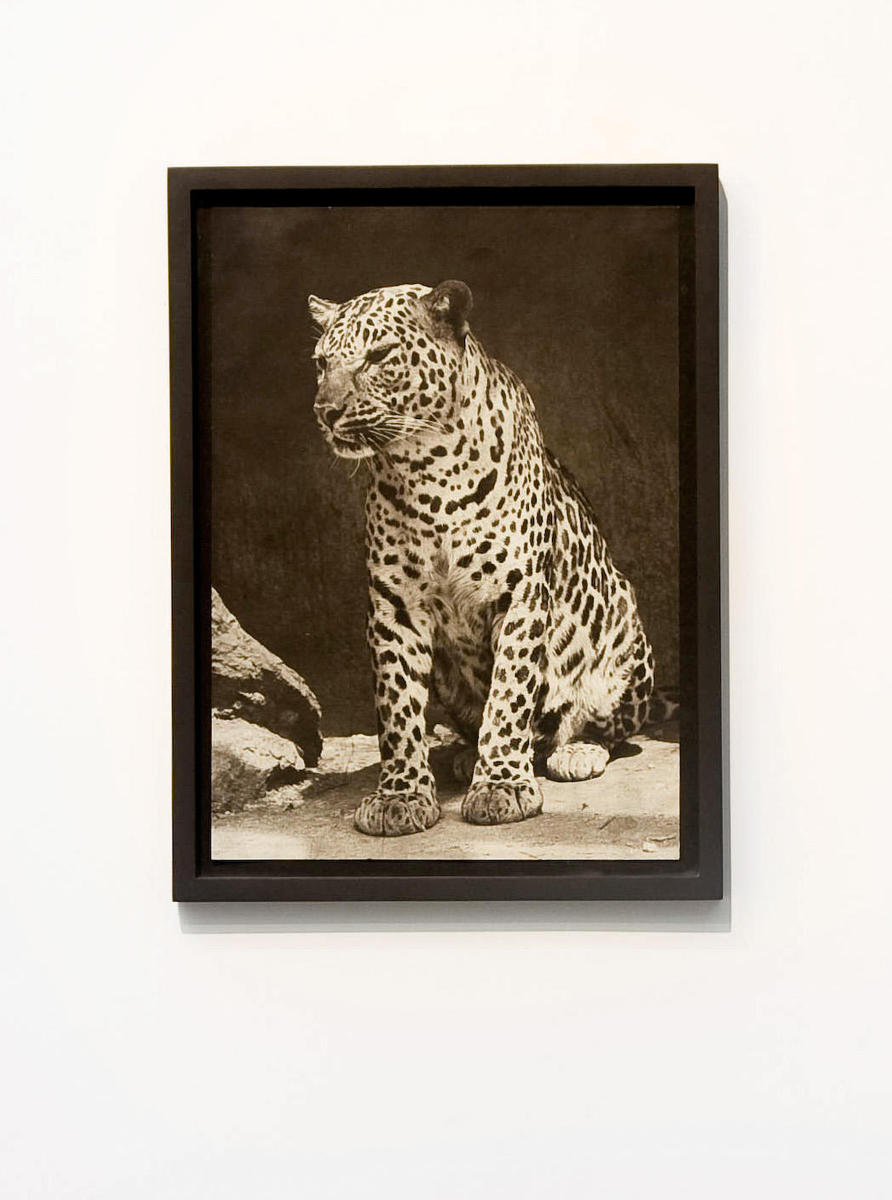

Haris Epaminonda’s first solo exhibition at Rodeo Gallery in Istanbul featured ten discrete installations. They ranged in complexity from a single image, found and framed, to an elaborate collection of objects, including five small statuettes, three plinths, a chunk of rock and a postal scale, a low-slung table, a bowl made of clay, a glass box with a book inside, a meticulous assortment of fifty stones and fossils arranged on a folded piece of cloth, and nine more images, all similarly found and framed and stacked against a wall like the unsold stock of a gallery or a junk shop.

Almost all of Epaminonda’s work — however it’s expressed in its final form, whether as videos, Polaroids, fragile collages, or tightly packed installations — consists of stuff she finds in the world around her. She is a consummate and possibly obsessive collector of rarities, curiosities, and seemingly random, mundane ephemera. The only things she “makes” are supports, such as frames and pedestals and plinths, and occasional sculptural and architectural details, such as the thin wooden square with diminutive legs that, for the show in Istanbul, wrapped around one of Rodeo’s central concrete columns.

By placing substantial emphasis on the structures that prop up, contain, or in some cases obscure her found objects and excised images, Epaminonda plays with conventional modes of exhibition-making and museum display. But her approach is far from that of a cool institutional critique. While the forms themselves are minimal and austere, their function is warm, even affectionate, such that Epaminonda’s supports seem to embrace and protect and provide shelter for materials that have otherwise been discarded or forgotten.

Of course, much of that material — as with Epaminonda’s fertility figurines, in the installation Untitled #07 — is dated. The pages she pulls out of old books depicting archeological relics, colonial explorers and adventurers, tribal costumes and jewels, wild animals, and lush, untainted landscapes, are evidence of an earlier, more politically incorrect age, when anthropologists, ethnographers, and travel writers for National Geographic were free to characterize distant lands as savagely beautiful, backward, untouched by industry or modernity. But Epaminonda thoroughly strips this material of context, such that viewers are able to lose themselves in her own barely decipherable, yet strangely emotive, language — which, incidentally, she delicately yet steadfastly refuses to interpret or translate.

In the current climate of overly self-analyzed artistic production, Epaminonda is rare in that she doesn’t bother building any discursive or textual scaffolding around her work (biographical or geopolitical readings are therefore totally beside the point). For her contribution to the catalog of the 2009 Sharjah Biennial, for example, she eluded the editors’ request to respond to a survey (“Could you tell us about the work you’re showing in the biennial?” and “What challenges have you faced so far?”) by submitting an excerpt from Maurice Blanchot’s Friendship instead. Not an excerpt, exactly, but a photocopied spread of the first two pages of the book’s fourteenth chapter, entitled “Destroy.” Enigmatic outside its intended context (“Let us say it calmly: one must love in order to destroy”), the section ends, mid-sentence, on the word “without.”

Substituting a selection from Blanchot’s text in place of her own thoughts or ideas, Epaminonda dodged the more or less explicit demand to explain herself, her work, and her practice. Rather than a description or exposition of her Sharjah commission — consisting of fifteen Polaroids and a video projecting a single still image of a zebra, color streaked across its neck, being immobilized by three men, one of whom seemed rather shocked to have gotten two hands around the animal’s tail — the artist simply added another layer of her art, which hinges considerably on oblique associations and gestures.

Epaminonda’s work also seems intimately tied to, or at least fascinated by, the extinction and obsolescence of its own medium, be it the Polaroid or the book. All of her exhibitions are, for the most part, serialized in volumes. Her ongoing collaboration with the artist Daniel Gustav Cramer, The Infinite Library, involves binding together pages from different books to create new ones. Whenever Epaminonda does talk about her work, she likens it to poetry, making sentences, creating systems based on rhythms and patterns — all of which sounds far more literary than visual. And perhaps, in a way, that’s what the work is all about, creating the imaginative space and potential that is usually associated with literature, with the added challenge of doing so solely in visual and spatial terms, without recourse to the trappings of language or narrative.