Tehran

Fajr Film Festival

February 1–11, 2007

In its twenty-fifth year, Tehran’s Fajr Film Festival featured sixty films in several competitive sections, selected by a board of gatekeepers who adhere to conditions laid out by the Ministry of Culture and decide what should be shown when and where.

Twenty-eight features, plus a fifteen-director portmanteau film, Farsh-e Irani (Persian Carpet), competed for the Crystal Simorgh in the national film competition. Deemed the highlight of the festival before it began, Farsh-e Irani attempted to take on the subject of one omnipresent cultural element in Iranian life.

It’s a testament to the power of the Iranian carpet that the big names of Iranian cinema — including Majid Majidi, Behram Bezaii, Bahman Farmanara, and Abbas Kiarostami — were brought together “under one loom” for the first time. The film, when considered as a single feature, was a disappointment. Jafar Panahi’s standout contribution, which focused on the pecuniary aspect of the rugs and how investing in them affects family relations, was a standout, however.

Audiences at Fajr tend to be quite participatory when it comes to the crowded public screenings of competition section films. Directors either relish the recognition or lash out indiscriminately, depending on the reactions of audience and the jury to their work. Competition winners invariably maintain that winning the award will make their work harder to do next time, but in practice their subsequent films often seem more conservative. Meanwhile, those who feel shortchanged usually provide no shortage of drama; that drama has a special place in Tehranis’ hearts and is an integral part of festival entertainment.

The awards ceremony is quite distinct from the popular vote. Those who abide by conditions set by the Ministry of Culture tend to be the ones who both distribute and receive awards. Even this year’s “controversial” winner, Khoon Bazi (Mainline), generally followed approved trends, featuring drug problems in a broken family.

Khoon Bazi was about the prevalence of illegal drug use among Iranian youth. It was a somewhat unusual award-winner, given its quality and theme and the fact that it was a largely independent production. Bani-Etemad wanted to shake up middle-class cinephiles, and the film is a worthy, sharp reminder of the extent of hard drug use in Iran. But there was something of a conflict between the film’s innovative style — handheld cinematography, use of black-and-white with sepia, and febrile acting, especially by Bani-Etemad’s talented daughter, Baran Kowsari — and its message, which seemed to posit wayward family values as the source of the problem.

The Crystal Simorghs this year was shared by Rakhshan Bani-Etemad and Mohsen Abdolvahab’s Khoon Bazi and Mohammad Hossein Latifi’s war drama Ruz-e Sevvom (The Third Day). Despite multiple nominations, critical favorite Otobus-e Shabaneh (The Night Bus), an original take on war by director Kioumars Pourahmad, was largely overlooked.

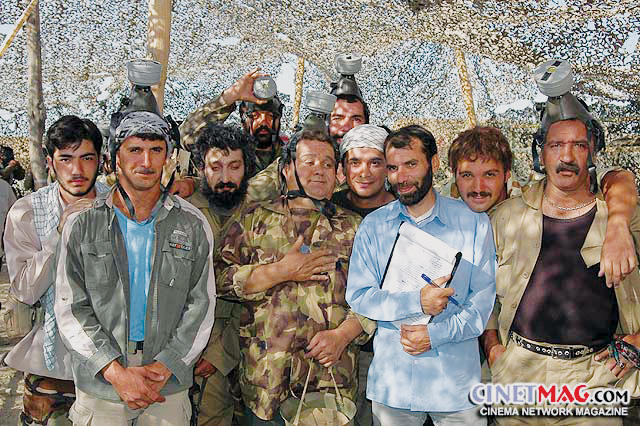

As mentioned, controversy is as much a part of Fajr as predictable awards ceremonies, and a bit of media hype can work wonders for ambitious producers. Ekhraji-ha (The Outcasts), a comedy about four hoodlums who enlist in the army during the Iran-Iraq War, drew massive crowds during the festival, causing traffic jams around the theaters. None of the lead characters go to the front for the usual heroic reasons, and the film’s message is ultimately one of tolerance—something of a U-turn for the director, Masoud Dehnamaki, who was known for publishing right-wing periodicals before he turned to directing films.

Convinced he would bag Best Film, Dehnamaki found that his film wasn’t even included in the official competition. At the closing ceremony, called onstage by producer Mohsen Kasesaz, who generously offered him his award, Dehnamaki declared cynically that “Iranian cinema is like its politics, and its politics is like cinema,” before leaving the stage, swearing about the bourgeois organizers. The Outcasts began its general screening during the Nowruz holiday in April and continues to break box office records.

In comparison, the sideshow of international films (including Bobby, The Caiman, and The Illusionist) was somewhat dull in entertainment terms. The festival should be commended for offering local audiences and critics the chance to see films denied distribution during the rest of the year, even if many of them end up cut by up to thirty minutes. Some local critics, while questioning Fajr’s censorship policies, tempered their comments by comparing Fajr’s international outlook to this year’s Cannes Film Festival program, which, unusually, didn’t include a single Iranian film — a decision which, in Iran, is generally understood to be political, rather than one of aesthetics.

Much as in the case of its American cousin, the Academy Awards, there is no competition as such at Fajr, and, in common with many international festivals, the Tehran showcase tends to be something of a formality that reflects the worldview of its organizers. For ten days a year, it entertains critics and audiences — but not always in the right way or for the right reasons.

— Hamed Safeaee

Translated by TehranAvenue

Berlin

Berlinale

February 8–18, 2007

After a golden 2006 festival, when Iran alone had seven films screened, this year’s Berlinale was something of a washout for Arab cinema in general and Iranian cinema in particular. Quizzed as to why the only Middle Eastern films present in competition were from Turkey and Israel, Berlinale director Dieter Kosslick pointed to the films outside the official selection, which were being screened for buyers and industry delegates in the market, rather than admitting to any bias or making reference to the humdrum state of filmmaking in the region. Most of the market films, however, had already premiered elsewhere; some, such as Bahman Ghobadi’s Half Moon, were festival veterans.

Joseph Cedar’s Beaufort, the story of the last unit of Israeli soldiers to be pulled out of southern Lebanon in 2000, had a good run, taking the Best Director prize, while Dror Shaul took the Generation 14plus award for young filmmakers with Sweet Mud, starring young discovery Tomer Steinhof.

In the Panorama sidebar section, Özer Kiziltan’s outstanding Takva: A Man’s Fear of God was presented as a cinéma vérité portrait of Muharrem (Müfit Aytekin), a debt collector and devout member of a conservative Islamic sect. Berlinale darling Eytan Fox delivered a fresh, if flawed, take on life in Tel Aviv with The Bubble, the story of three young gay peace activists (played by Ohad Knoller, Daniela Wircer, and Alon Friedmann) who befriend Ashraf (Yousef “Joe” Sweid), a Palestinian. They help him to stay on in Tel Aviv illegally, before politics catches up with their friendship.

Meanwhile, Hiner Saleem, of Vodka Lemon and Kilometer Zero fame, delivered more of the same with Dol, another road trip through Kurdistan defined by the Iraqi Kurd’s laconic style and ironic visual humor.

The participation of young Arab and Iranian filmmakers in Berlinale’s Talent Campus, a series of workshops and discussions, did offer some hope for future years. The talk at “Ex Oriente Pix,” a seminar led by seasoned directors and producers Ferid Boughedir, Michel Khleifi, Irit Neidhart, Simone Bitton, and Dora Bouchoucha, centered around that periodic question of whether it is possible to produce films in the region that aren’t defined by bombs, checkpoints, or war — or rather, whether it’s possible to gain international funding and distribution for individual tales that diverge from the expected.

— Marleen Dyett

Istanbul

Istanbul International Film Festival

March 31–April 15, 2007

Istanbul’s annual film showcase is traditionally more international than its older cousin, the Antalya Golden Orange Film Festival, but this year’s event felt almost like a celebration of homegrown cinema. The festival screened 237 films and featured a range of curated events, including master classes and talks by renowned directors such as Gus Van Sant, Tsai Ming-liang, Park Chan-wook, and Paul Schrader, but — reflecting the current buoyancy of the local industry — much of the focus was on the sixteen Turkish films in the national competition.

In previous years, festival programmers have found it difficult to select enough local films for the festival, given the paltry number produced; this year, production was up to over thirty (both commercial and “art”) films, and their quality as well as quantity was reflected in the festival’s program.

Nuri Bilge Ceylan’s Climates (which won the Best Turkish Film award) and Zeki Demirkubuz’s Destiny (Best Turkish Director and FIPRESCI awards) have both been hailed internationally, but there were also new discoveries — particularly Özer Kızıltan’s Takva: A Man’s Fear of God and Dervis Zaim’s Waiting for Heaven, an attempt to explore the possibilities of two-dimensional Ottoman miniature aesthetics on film.

Other films were indicative of new themes in popular Turkish cinema. Home Coming (Ömer Ugur), Zincirbozan (Atıl Inaç), and Beynelmilel (Sırrı Süreyya Önder and Muharrem Gülmez) all dealt with the (formerly taboo) subject of the 1980 coup d’état and its aftermath. These films have opened up an atypical, public space for discussion of the political and social consequences of the coup — something local audiences took up with enthusiasm. The Taylan brothers’ The Little Apocalypse and Onur Ünlü’s Police were also novel in their attempts to break down the boundaries between mainstream and art films, to be experimental while achieving the broad appeal of popular cinema. The Taylan brothers’ thriller, centered on an anticipated future Istanbul earthquake, was an especially noteworthy example of auteur cinema working within popular conventions.

In addition to the competitions, established sidebars, and inspired sections devoted to directors Pier Paolo Pasolini, Gus Van Sant, Bob Fosse, and Hayao Miyazaki, a small new section curated by celebrated author and film critic Fatih Özgüven, was a compelling and resolutely local element. Titled “Tears on Burning Rocks,” the section was dedicated to Rainer Werner Fassbinder and included some of his films, plus others that somehow touch or were touched by Fassbinder’s cinema. Directors such as Douglas Sirk and François Ozon were included, as well as some Turkish films Fassbinderesque in their treatment of gender, sexuality, and oppression. This section of the festival made for an exceptional dialogue between national and international films.

— Senem Aytaç